How Real-Life AI Rivals 'Chappie': Robots Get Emotional

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Artificial Intelligence will rule Hollywood (intelligently) in 2015, with a slew of both iconic and new robots hitting the screen. From the Turing-bashing "Ex Machina" to old friends R2-D2 and C-3PO, and new enemies like the Avengers' Ultron, sentient robots will demonstrate a number of human and superhuman traits on-screen. But real-life robots may be just as thrilling. In this five-part series Live Science looks at these made-for-the-movies advances in machine intelligence.

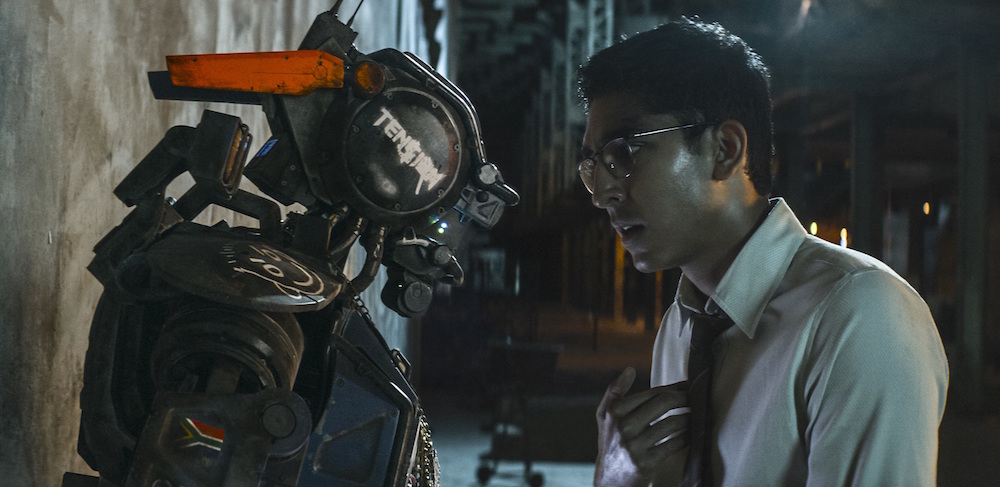

In the film "Chappie," released on March 6, the titular robot becomes the first droid to experience emotion, sowing chaos and initiating a fight for its own survival. Though popular conceptions have long pictured robots as unfeeling beings, cold as the metal in their circuits, Chappie's emotional awakening has both sci-fi precedence (see 1986's "Short Circuit," for example) and real-life analogs.

Outside of Hollywood, engineers are working to more fully integrate emotional and artificial intelligence. The field of "affective computing" aims, broadly, to create AI systems with feelings. To do this, the machines would have to achieve one or more pillars of the "affective loop:" recognize emotion, understand emotion in context and express emotion naturally, Joseph Grafsgaard, a researcher at North Carolina State University, told Live Science.

Grafsgaard's own lab last year produced an automated tutor system that can recognize students' emotions and respond appropriately. The team used various sensors and facial-recognition monitors to measure signals like how close a student is to the screen and the movement of facial muscles, which revealed when the student was showing an emotion like boredom. The researchers then fed this data into their AI system outfitted with the same sensors. [Super-Intelligent Machines: 7 Robotic Futures]

"In my approach, I use nonverbal cues" to identify emotions, Grafsgaard said. "This is closest to what psychologists have been doing."

Even so, "the systems right now are purpose-built. They are not adaptive systems yet," he said. That's because, for example, a furrowed brow has a different meaning in a tutoring session than when someone is viewing a piece of marketing.

Even a computer capable of all three pillars could not be said to "feel," Grafsgaard said, because the technology right now doesn't let these bots recognize themselves as "selves." "Under current techniques, there is no consciousness," he said. "The techniques do not incorporate a 'self' model."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Others, however, say work on emotion in AI will inevitably lead to feeling machines. Famous futurist Ray Kurzweil, who predicts sentient machines by 2029, gives emotional intelligence an important place in that development. Once robots understand natural language, Kurtzweil told Wired, they can be considered conscious.

"And that doesn't just mean logical intelligence," he said. "It means emotional intelligence, being funny, getting the joke, being sexy, being loving, understanding human emotion."

Check out the rest of this series: How Real-Life AI Rivals 'Ultron': Computers Learn to Learn, How Real-Life AI Rivals 'Ex Machina': Passing Turing, How Real-Life AI Rival 'Terminator': Robots Take the Shot, and How Real-Life AI Rivals 'Star Wars': A Universal Translator?

Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Michael Dhar is a science editor and writer based in Chicago. He has an MS in bioinformatics from NYU Tandon School of Engineering, an MA in English literature from Columbia University and a BA in English from the University of Iowa. He has written about health and science for Live Science, Scientific American, Space.com, The Fix, Earth.com and others and has edited for the American Medical Association and other organizations.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus