Cold Exposure Deaths Higher in Rural Western Areas of US

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

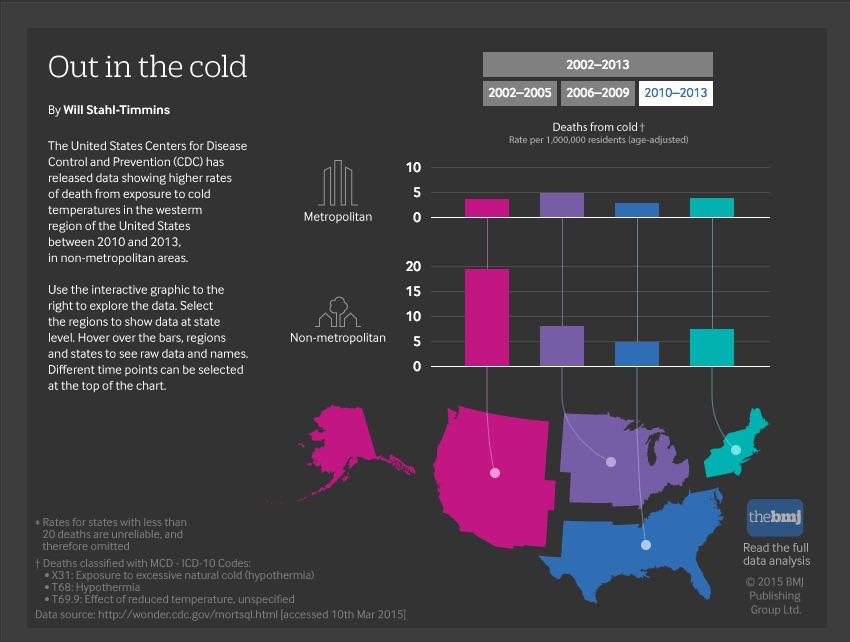

Every year, thousands of people die from exposure to the cold across the United States. But there are far more of these cold-related deaths in rural counties in the West than there are in other areas of the country, a new study finds.

About 5,800 people died from exposure to cold from 2010 to 2013, according to the study, from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which was published online today (March 12) in the British Medical Journal.

"With all of our resources, we will have elderly people or very young babies who are still simply dying because the weather is cold, which is completely preventable," said Dr. Susi Vassallo, an associate professor of emergency medicine at the New York University School of Medicine, who was not involved with the study.

After adjusting for age, the CDC researchers found that the cold-related death rate in rural western areas was 20.5 deaths per 1 million people. (Western states include those along or west of the Rocky Mountains.) The mountain states had a higher rate of cold-related deaths than the coastal states, with the highest rates in rural Arizona and New Mexico, the researchers found. [Top 10 Leading Causes of Death]

For comparison, the death rate in other nonmetropolitan areas of the country ranged from 4.5 to 7.8 deaths per 1 million people. The cold-related death rates in the nation's metropolitan areas were even lower, ranging from 2.9 to 5.0 deaths per million, the study found.

It's unclear exactly why areas in the West have a higher rate of cold-related deaths. Studies suggest that people have an increased risk of dying from the cold if they live in places with rapid temperature shifts, large shifts in nighttime temperatures or high elevation, according to a 2014 CDC report, and all of these occur in regions such as the Rocky Mountains.

Furthermore, weather-related deaths — including those from storms, lightning and floods — are two to seven times higher in low-income counties than in high-income counties, the 2014 study found. Many of the rural counties in the American West have high rates of poverty.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The groups at greatest risk of cold-related deaths include the elderly, infants, men, African Americans and people with pre-existing chronic medical conditions, such as cardiovascular and respiratory illnesses, that 2014 report also found.

Vassallo noted that the new report did not distinguish among people who had died from outdoor accidents, such as mountaineers who lose their way, and those who died while living on the streets or enduring other hardships, such poverty.

But still, she said, people who are elderly or who have low levels of income may not turn on heat in the winter, so they can save money. And people in rural areas are usually located far from caring neighbors and medical and social services that can help people in need, she said.

Unless these services expand and improve, these cold-weather deaths will likely continue, she said. Since the 1950s, North American winter temperatures have grown milder, but the country has also seen an increase in storm frequency and intensity during the fall and winter, according to the 2014 U.S. National Climate Assessment. Extremely low temperatures are not uncommon during these times, the assessment found.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus