Ebola Bomb: Possible, But Not So Easy to Make

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

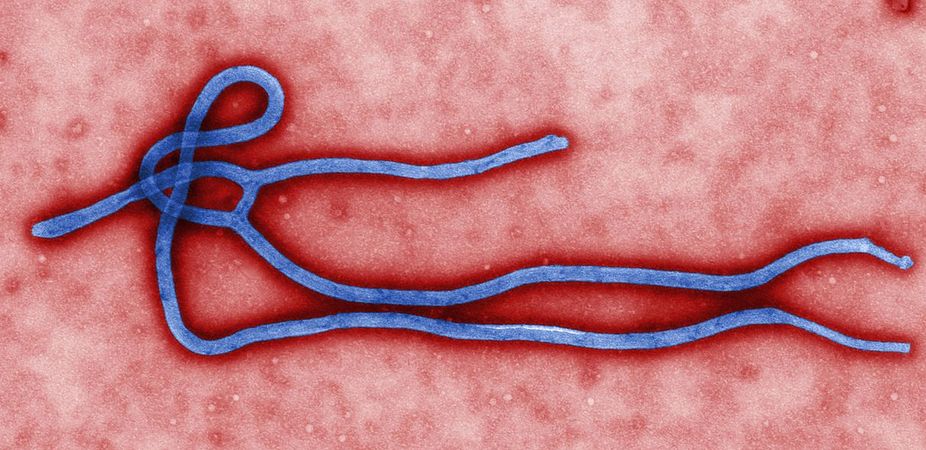

If some worst-case scenarios are to be believed, then terrorist groups could use the recent outbreak of Ebola in Africa to their advantage. By using the Ebola virus as a biological weapon, the story goes, these groups could wreak havoc around the globe.

But the idea that Ebola could be used as a biological weapon should be viewed with heavy skepticism, according to bioterrorism experts. Although deadly, Ebola is notoriously unstable when removed from a human or animal host, making weaponization of the virus unlikely, two experts told Live Science.

That's not the view posited by Peter Walsh, a biological anthropologist at Cambridge University in the United Kingdom. The world should be taking the threat of an Ebola bomb very seriously, Walsh said in a recent interview with the British tabloid The Sun. [7 Technologies That Transformed Warfare]

Walsh warned that terrorists could "harness the virus as a powder," load it into a bomb, and then explode the bomb in a highly populated area, CBS Atlanta reports.

"It could cause a large number of horrific deaths," Walsh told The Sun.

But the idea of Ebola being harvested for use in a "dirty bomb" sounds more like science fiction than a real possibility to bioterrorism experts.

Dr. Robert Leggiadro, a physician in New York with a background in infectious disease and bioterrorism, told Live Science that although Ebola is listed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as a possible bioterrorism agent, that doesn’t necessarily mean the virus could be used in a bomb.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The thing about Ebola is that it's not easy to work with," Leggiadro said. "It would be difficult to weaponize."

And Hamish de Bretton-Gordon, COO of SecureBio, a chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear security firm in the United Kingdom, said that claims like Walsh's are an example of fear-mongering.

"The chance of the Zaire strain of Ebola being made into a biological weapon is less than nil," de Bretton-Gordon said, referring to the strain of Ebola that is causing the current outbreak in West Africa. "It's just not going to happen."

These experts pointed to three main reasons why Ebola isn't likely to be used as a bioterrorism agent anytime in the near future.

Weaponization woes

In order to make Ebola into a biological weapon, a terrorist organization would need to first obtain a live host infected with the virus, either a human or an animal. Only a few animals serve as Ebola hosts, including primates, bats and forest antelope, and none of these are particularly easy to detain.

Once a live host was captured, it would need to be transported to what de Bretton-Gordon called a "suitably equipped" laboratory, in order to extract the virus. Such laboratories, known as Category 4 or Biosafety level 4 Labs, are not easy to come by, he said.

In fact, there are less than two dozen Category 4 laboratories in the world, according to the Federation of American Scientists. Failure to work inside one of these labs when handling the Ebola virus would likely result in the death of whoever is doing the weaponizing, de Bretton-Gordon said.

If a terrorist organization were able to obtain a host, gain access to a Category 4 Lab and isolate the virus, they still would have a lot of work to do before they could use Ebola as a biological weapon.

"The process to weaponize a biological agent is complex and multi-staged, involving enrichment, refining, toughening, milling and preparation," de Bretton-Gordon said.

Ebola is not well suited to any of these processes, which are designed to ensure that the biological agent survives the traumatic experience of being fired from a rocket, dropped from an aircraft and submitted to harsh climatic conditions.

Hardly hardy

There's a reason you haven't heard about Ebola being used as a biological weapon in the past: it hasn't been. And that's because Ebola, unlike other disease-causing agents, is not very hardy, de Bretton-Gordon said.

"The reason anthrax has been the biological weapon of choice is not for its mortality rate — when properly weaponized it is similar to Ebola— but for the fact that it is exceptionally hardy," de Bretton-Gordon said. "Anthrax can and will survive for centuries in the ground, enduring frosts, extremes of temperature, wind, drought and rain before re-emerging."

In contrast to the hardiness of anthrax bacteria, the Ebola virus is sensitive to climactic conditions, like exposure to sunlight and extreme temperatures, de Bretton-Gordon said. Once the virus is removed from its host, it requires a very particular environment in which to survive, including relatively high temperatures and humidity, he said.

"Assuming a terrorist organization manages to capture a suitable Ebola host, extract the virus, weaponize the virus, transport the virus to a populated city and deliver the virus, it is entirely likely that the sub-optimal climatic conditions of a Western city will kill it off relatively quickly," de Bretton-Gordon said.

Slow transmission

Many of the deadliest viruses and toxins that the CDC categorizes as possible bioterrorism agents can spread from person-to-person through the air. These airborne toxins, such as anthrax or plague, could be released into the environment, through a dirty bomb or some other means, and could infect many people very quickly. [7 Devastating Infectious Diseases]

But as de Bretton-Gordon explained, that's not how Ebola works.

"Contrary to popular myth — probably from the film "Outbreak" — Ebola is not airborne, and relies on transmission through the consumption of contaminated meat and direct contact with infected bodily fluid," de Bretton-Gordon said.

It's method of transmission makes Ebola less contagious than airborne viruses, and therefore easier to contain, provided that strict protocols for containment are followed, de Bretton-Gordon said. When the proper protocol is followed, Ebola is considerably less contagious than common viruses, such as measles or the flu, he said.

Follow Elizabeth Palermo @techEpalermo. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus