Belly-Flopping Icebergs Could Help Track Glaciers

ANCHORAGE, Alaska — Icebergs that tumble into the ocean are the source of unusual "earthquakes" recorded at Alaskan glaciers, researchers said yesterday (May 1) here at the annual meeting of the Seismological Society of America.

Though no one regularly follows these funky seismic signals, analyzing them could give researchers a better understanding of glaciers, said Alaska state seismologist Michael West.

"There are thousands of these events to work with," West said. "The seismic network can act as a tool for monitoring glaciers."

West said that watching how glaciers shimmy and shake could provide unexpected insights into the seasonal changes that happen at remote, inaccessible glaciers, as well as help monitor the ice sheets' complex response to climate change.

For example, Hubbard Glacier, College Fjord's glaciers and Yahtse Glacier in southern Alaska all hit their peak iceberg production in different months, but researchers don't know why, West said. [Image Gallery: Remote Alaska's Rugged Beauty]

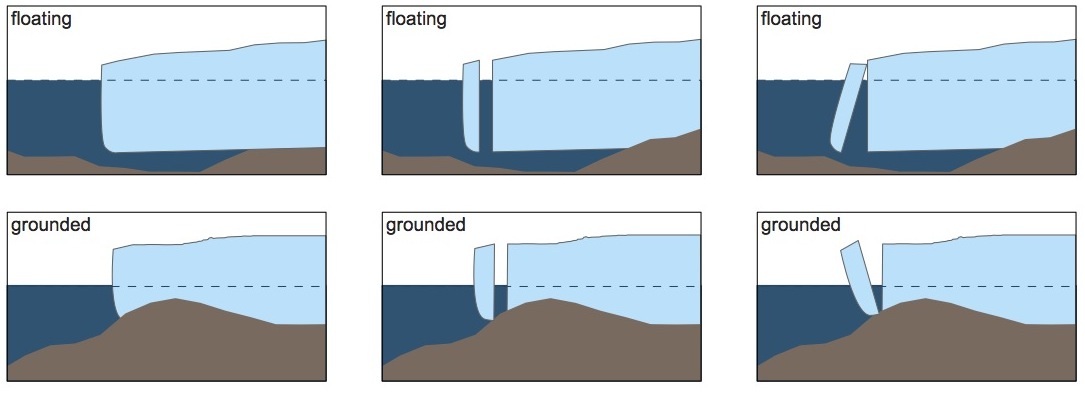

And when Alaska's rapidly retreating Columbia Glacier got stuck on an underwater pile of jumbled rock in August 2010, West said there was a sudden jump in the number of 'splashdown' quakes from icebergs. These are quakes recorded when giant ice chunks peel off the front of the glacier, then tip off the underwater hill and belly flop into the sea.

"It's like kids at a pool party," West said. "They cannonball into the water."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But the seismic record was much quieter before the glacier grounded itself, West said. That's because the end of the glacier was floating in the ocean, and calving icebergs dropped without a toppling splash off an underwater rise.

The splashdown events lack the hallmarks of earthquakes unleashed by rocks, West said. Still, they're similar enough to real shakers to trigger automatic quake-detection software, so state seismologists must find and delete these false positives, to ensure the record of earthquake activity is accurate.Since 2007, when researchers' network of seismic listening posts was greatly expanded in Alaska's glacier-cloaked southeastern mountains, the system has detected more than 2,800 of these splashdown quakes. Their size is equivalent to earthquakes between magnitude-1 and magnitude-3. For comparison, some 35,000 earthquakes shake Alaska each year.

If West adds glaciers to Alaska's watch list, then the icy rivers will join a long list of natural and man-made phenomena now tracked with seismometers, including volcanoes, meteorites, nuclear blasts, landslides and even hurricanes.

Cracking glaciers can also cause other kinds of quakes. There are glacier quakes within their flowing ice, and the giant ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica occasionally let loose with ice quakes equivalent to magnitude-5 earthquakes.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @OAPlanet, Facebook and Google+. Original article at Live Science's Our Amazing Planet.