Tricky Parasite Creates Deadly Threesome

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

In a devious ploy that might impress the most hardened crime lord, parasitic worms alter their aquatic hosts' sense of smell so they are more likely to be eaten by fish that serve as the parasites' hosts later in life, new research reveals.

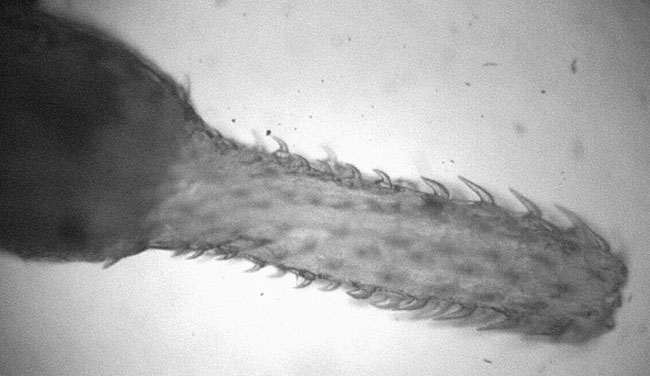

Parasites often swap hosts during their lifetimes. The parasitic worm Pomphorhynchus laevis spends its youth in the body cavities of freshwater shrimp-like crustaceans known as amphipods before reaching sexual maturity and moving to roomier lodgings inside predatory fish. The worms use their spiny proboscises, mouth-like tubes, to pierce and hook onto intestinal walls.

Prior studies had revealed that amphipods infected with the worm preferred swimming in the open water during the day when uninfected crustaceans normally would hide from predators in dark places. Still, this was not definitive proof that infected amphipods were on suicide missions.

Instead, evolutionary biologist Sebastian Baldauf at the University of Bonn in Germany and his colleagues investigated what happened when amphipods were exposed to the sight and smell of predators. They first collected hundreds of infected and uninfected amphipods from a brook, as well as 10 perch fish from a lake.

When amphipods were in a tank separated from a perch by a transparent net, thereby allowing for the transfer of chemical signals, the uninfected crustaceans stayed away from the fish while the infected ones preferred staying near the predator.

At the same time, when the amphipods were in a tank separated from a perch by a transparent partition, neither infected nor uninfected crustaceans preferred or avoided the predator side. This suggested that visual cues alone do not cause infected amphipods to seek death.

In a final set of experiments, the researchers found that when amphipods were in a tank that had clean water poured into one side and water from a tank containing a perch on the other, the infected crustaceans often opted for the fishy side while the uninfected shunned it.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This may be the first time that scientists have shown a parasite increases its chance to reach another host by manipulating the sense of smell of its current host, Baldauf told LiveScience. Future research could entail seeing what difference multiple parasitic infections have on amphipods, he said.

The findings are detailed in the January issue of the International Journal for Parasitology.

- VIDEO: Sneaky Parasite Filmed While Infecting Blood Cells

- VIDEO: How a Parasitic Plant Strangles its Host

- Top 10 Animal Senses Humans Don't Have

- Inside Look: How Viruses Invade Us

- Vote Now: The Ugliest Animals

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus