What Caused the Deadly Midwestern Tornado Outbreak?

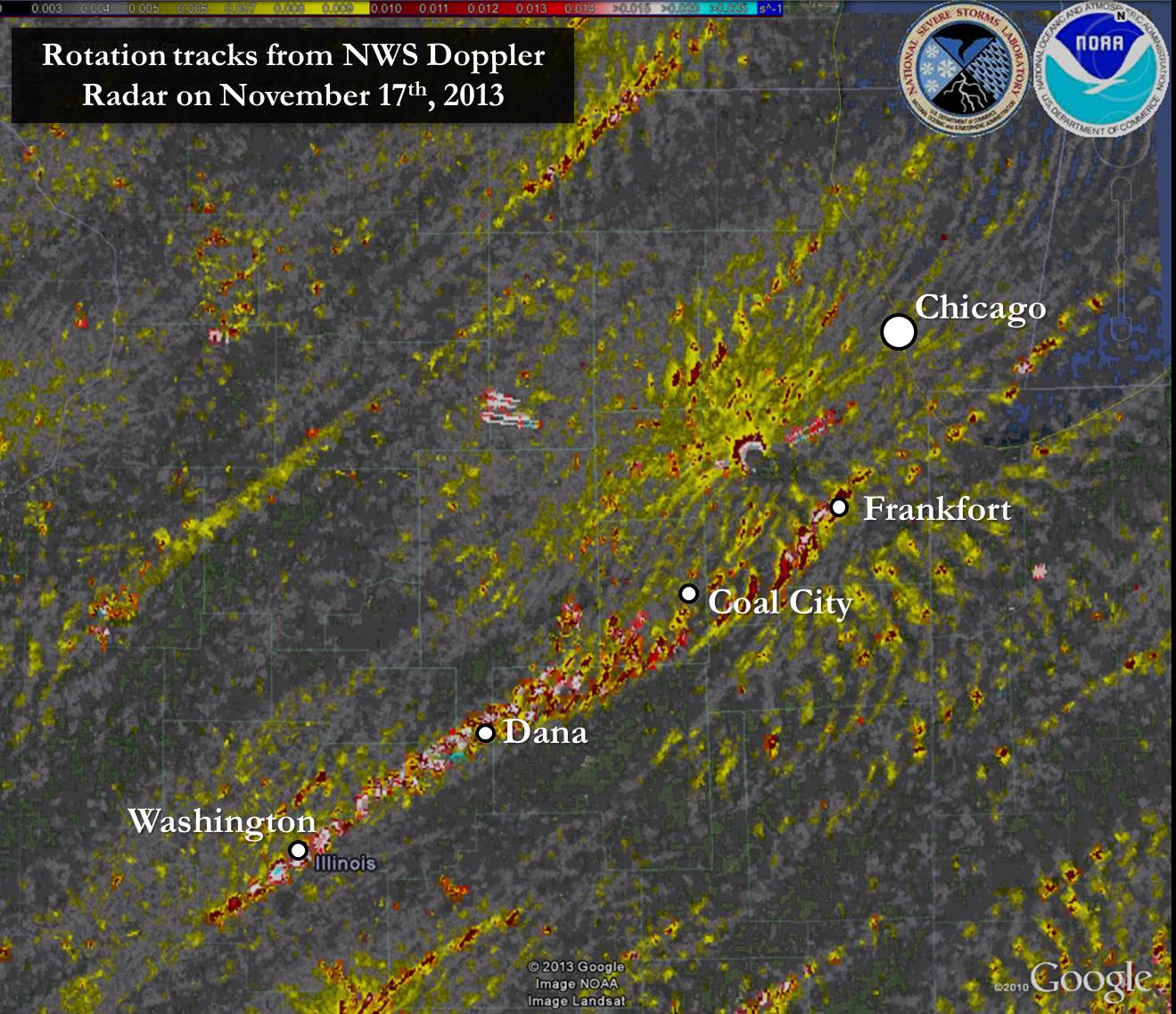

A slew of tornadoes slammed the state of Illinois and surrounding areas yesterday (Nov. 17), killing six people and damaging or destroying thousands of homes, according to news reports. Eighty-one tornado reports were submitted to the National Weather Service (NWS) yesterday, most of them in the Land of Lincoln, though more than one report could be for the same tornado.

The devastation was significant enough that Gov. Pat Quinn declared seven counties state disaster areas, including Tazewell County, where a twister left parts of the town of Washington in ruins.

One of the tornadoes in this area was preliminarily declared an EF-4, the second strongest type of tornado, said Illinois state climatologist Jim Angel. These twisters pack winds between 166 to 200 mph (267 to 322 km/h) and are strong enough to destroy sturdy houses and hurl cars.

Whence the tornadoes

Sunday started out feeling "like a spring day" (a time of year more associated with tornadoes) throughout much of Illinois, with high humidity and sunny skies, Angel told LiveScience. But then it took a turn for the worse as a low-pressure system over the Great Lakes pulled in a cold front from the north and west and into central and northern Illinois.

The tornado outbreak was caused by this clash of cold, dry air from the north and warm, moist air from the Gulf of Mexico, some of which was also pulled northward by the Great Lakes' low-pressure system. The cold air acted like a "wedge," forcing up the hot air, since the balmier air is less dense. As this soupy air rose, its moisture condensed, forming clouds and releasing energy in the form of high winds and thunderstorms, said Greg Carbin, a meteorologist with the NWS' Storm Prediction Center in Norman, Okla. [Infographic: How, When & Where Twisters Form]

As this warm and cold air mixes together, it can cause swirling funnels or gyres of air, which can then be flipped vertically to form tornadoes by wind shear, which is a change in wind speed or direction with height, Carbin told LiveScience. Wind shear, and the tornadoes it helps spawn, was also increased by an intensified jet stream, a thin ribbon of air that loops around the Northern Hemisphere. The jet stream was strengthened by the collision of cold and warm air masses, powered by the flow of energy from hot to cold air, Carbin said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

'Second tornado season'

Although more tornadoes form in the spring, there is a second spike of them in the fall, particularly in November. Both seasons are "transition periods," where cold and warm air can come together, bringing with them the ingredients necessary to create thunderstorms and tornadoes. Some have rightfully called this period of the fall the "second tornado season," Carbin said.

A study by Angel and colleagues found that in Illinois, as with other areas in the central and southern United States, there is a small November spike of tornadoes, at least relative to October and December. Still, the number is dwarfed by the amount of twisters in the spring. Angel found that there have been 68 November tornadoes in Illinois in the past 50 years, compared with 500 over the same time period in each month of April, May and June. This outbreak, then, will add significantly to this total, Angel said.

The outbreak itself is "atypical, but not unheard of," Carbin said. The last similar-sized one took place on Nov. 15, 2005, when there were scores of tornadoes throughout the Midwest. On average, such an outbreak in November can be expected once every seven years, Carbin said.

Email Douglas Main or follow him on Twitter or Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook or Google+. Article originally on LiveScience.