Ancient Roots: Flowers May Have Existed When First Dinosaur Was Born

Newfound fossils hint that flowering plants arose 100 million years earlier than scientists previously thought, suggesting flowers may have existed when the first known dinosaurs roamed Earth, researchers say.

Flowering plants are now the dominant form of plant life on land, evolving from relatives of seed-producing plants that do not flower, such as conifers and cycads.

"Flowering plants were the last group of plants appearing in Earth's history," said Peter Hochuli, a paleobotanist at the University of Zürich's Paleontological Institute and Museum and a co-author of the new study. "They are an extremely successful group on which all terrestrial ecosystems today depend, including the existence of humanity."

Flowering plants, or angiosperms, became the dominant plants about 90 million years ago, when the dinosaurs still roamed the Earth. However, the exact time when these plants originated remains hotly debated.

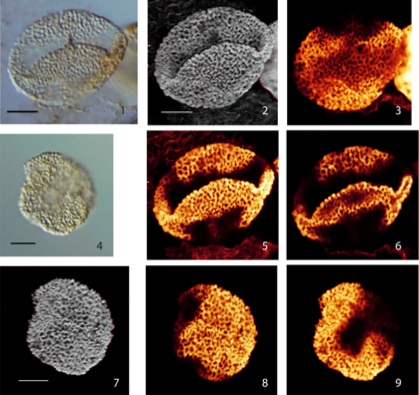

Now, scientists have unearthed ancient pollen grains with microscopic features typically seen in flowering plants. These well-preserved fossils, discovered in two core samples drilled in northern Switzerland, are about 245 million years old, dating back to the earliest known dinosaur in the Middle Triassic period. [See Images of the Earliest Known Dinosaur]

"Our findings suggest that the origin of flowering plants is rooted much deeper than originally thought," Hochuli told LiveScience.

Pollen grains are small, robust and numerous. This makes them easier to find in the fossil record than comparably large and fragile leaves and flowers. After analyzing the structure of these grains, the researchers suggested that the associated plants werepollinated by insects — most likely beetles, as bees did not evolve until about 100 million years later.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Six different types of pollen were found in the ancient samples, revealing that flowering plants back then may have been considerably diverse. The researchers have seen these pollen grains in both Switzerland and the Barents Sea, north of Scandinavia. However, back in the Middle Triassic, both areas were located in the subtropics, and the region that is now Switzerland was much drier than the Barents Sea region, suggesting the flowering plants spanned a broad range of environments.

The fossil record of flowering plants is continuous, dating back 140 million years. Until now, the fossil record of flowering plants suggested they dominated the planet rather quickly after their earliest appearance. "This sudden appearance has bothered scientists ever since Darwin, who called the origin of flowering plants an 'abominable mystery,'" Hochuli said.

These newfound fossils reveal that flowering plants may have existed more than 100 million years longer than previously thought. This increased span of time might help explain how flowering plants spread, diversified and prevailed on land.

The ancestors of flowering plants currently remain a mystery, and scientists aren't sure what kind of events or conditions might have spurred their origin.

"So far, no direct ancestors of flowering plants are known," Hochuli said. "Some groups of plants are suspected to be closely related. But the evidence is weak, and most of these groups are thought to be too specialized to be at the base of the flowering plants."

Hochuli and his colleague Susanne Feist-Burkhardt detailed their findings Oct. 1 in the journal Frontiers in Plant Science.

Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus