California Tsunami Would Have Costly Aftermath

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

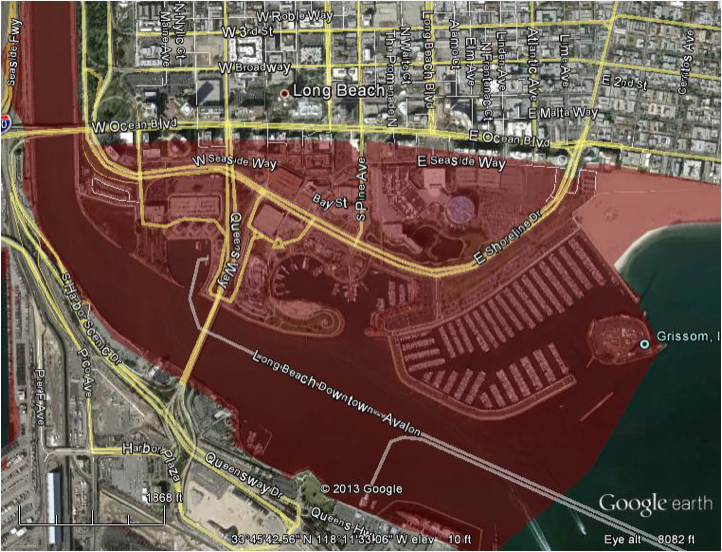

The fearsome aftermath of a tsunami striking California might cost at least $3.4 billion to repair, but neither of the state's nuclear power plants would be damaged, suggests a new analysis that could help officials and the public prepare for a tsunami and reduce risks before any such disasters happen.

Ever since the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami claimed about 250,000 lives, scientists have investigated the risks a tsunami crashing against the United Statesmight have. The fact the 2011 Tohoku-Oki earthquake and tsunami in Japan killed another 20,000 or so people and triggered a nuclear disaster further underscored the importance of such research, especially since the deadly wave also swept through California, albeit at a lesser strength, and caused $50 million to $100 million of damage.

Giant earthquakes can occur off the Alaskan coast, where the tectonic plate underlying the Pacific Ocean is diving underneath the continental plate underneath North America — in fact, the second-largest recorded earthquake in history was a magnitude-9.2 at this zone in 1964. The result could be a tsunami reaching down to California.

Six independent teams of scientists modeled a tsunami created by a magnitude-9.1 earthquake offshore the Alaskan peninsula as if it happened at nearly noon Pacific Time on Thursday, March 27, 2014, the 50th anniversary of the 1964 Alaska quake and tsunami. The federal and state researchers wanted to see the likely dangers such a tsunami would pose for California. [Waves of Destruction: History's Biggest Tsunamis]

"We created a scenario of what a plausible bad tsunami would be for California," researcher Lucy Jones, U.S. Geological Survey Science Advisor for Risk Reduction, told LiveScience.

Tsunami hazard

According to the model, it would take nearly six hours for the tsunami to crash into San Diego. After accounting for the amount of time needed to confirm the magnitude of any earthquake in Alaska, see whether it generated a tsunami, and calculate when it might hit, Southern California might have 3.5 hours of warning that a tsunami was on the way, while Northern California might only get two hours of warning, Jones said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The good news is that three-quarters of California's coastline is cliffs, and thus immune to the harsher and more devastating impacts tsunamis could pose," Jones said in a statement. "The bad news is that the one-quarter at risk is some of the most economically valuable property in California."

The bent shape of the California coast would lead the height of the tsunami approaching from the north to be significantly reduced in Southern California. As such, the tsunami hazard from this scenario is generally less in Southern California than elsewhere along the state's coast, although some areas of Southern California may be more vulnerable because they are low in elevation or have more people and maritime assets concentrated on the coast.

The greatest economic impact to California from tsunamis comes from damage to ports, harbors and other coastal properties. For instance, such a tsunami could damage or sink a third of all the boats in California marinas and damage or destroy two-thirds of the docks. Altogether, repairing California marinas, coastal properties, and the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach might cost about $3.4 billion, researchers estimated.

About 250,000 people live in the zones most inundated by the scenario and would likely have to be evacuated. An additional quarter of a million tourists and visitors might be on the coast if the scenario occurred in March. Tourist numbers could increase into the millions during the summer months.

Evacuation plans are key for those in potential tsunami inundation zones. "The best way to survive a tsunami is to not be there," Jones said. [No, You Can't Outrun a Tsunami]

Environmental damage

Furthermore, this scenario could lead to damage to the environment by many means, such as debris from damaged ships, piers and buildings, or raw sewage from inundated wastewater treatment plants. Still, in this scenario, neither of California's nuclear power plants are in danger of inundation.

If authorities do nothing further to prepare for a tsunami, losses from the interruptions to business after the disaster might reach about $6 billion. However, the researchers stress these losses can be reduced by 80 to 90 percent by implementing resilience strategies for recovery. For instance, ports might cross-train labor so they can fill in needed jobs if necessary and maintain extra capacity to keep operating despite setbacks. And such measures could have benefits beyond these in the aftermath of a tsunami.

"A lot of what you would do to prepare for one disruption can help you prepare for others," researcher Anne Wein, a U.S. Geological Survey operations research analyst in Menlo Park, Calif., told LiveScience.

The scientists detailed their plan on Sept. 4 in the U.S. Geological Survey's Science Application for Risk Reduction (SAFRR) Tsunami Scenario. They are now meeting with tsunami hazard working groups in several coastal Californian counties to discuss their findings.

"We need to get the word out, and we want to take insights from social science research on how to do that," Jones said. "Rather than saying how awful it is going to be, we want to ask people whether they're going to be ready to take care of their families, to be the people helping others rather than be the people being helped."

Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus