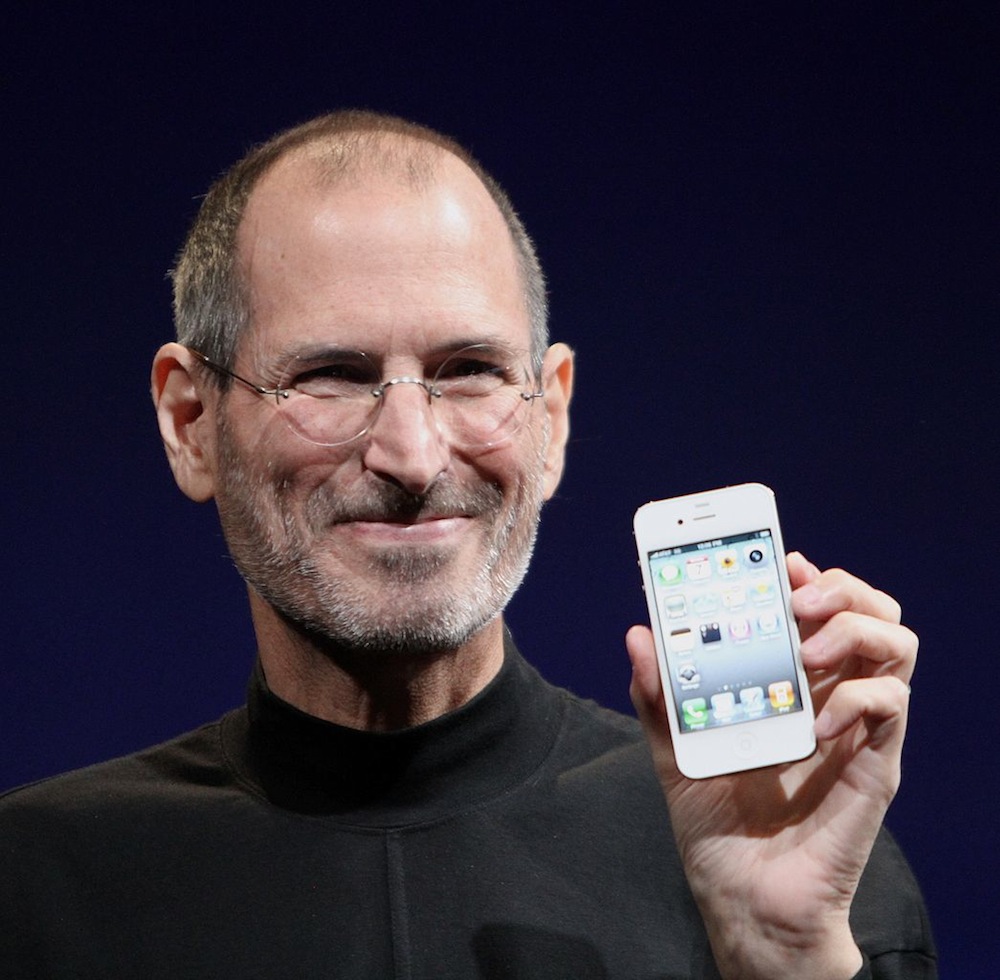

Obsession: The Dark Side of Steve Jobs' Triumphs

At the turn of the millennium, "Think Different" was the widely acclaimed advertising campaign for Apple Inc. But for company chairman Steve Jobs, thinking differently was more than just a slogan — it was an unavoidable fact of life.

Jobs — subject of a new biopic, "Jobs" — was a typical obsessive, according to author Joshua Kendall, and Apple's leader probably had a little-known disorder that psychiatrists now refer to as obsessive-compulsive personality disorder, or OCPD.

Is this a case of psychiatric overreach, in which any human quirk is declared a dangerous pathology (especially if Big Pharma can invent a pill for it)? Or did Jobs' undeniable success at Apple — perhaps the most imaginative and successful company of the 21st century — cost him his happiness, his family and even his health? [Creative Genius: The World's Greatest Minds]

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) describes OCPD as "a mental health condition in which a person is preoccupied with rules, orderliness and control." It often runs in families, but scientists are unclear whether genes, environment or a combination of these factors are behind the disorder.

OCPD or obsessive-compulsive disorder?

Though they're similar, the contrast between OCPD and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) couldn't be starker: People with OCD have unwanted thoughts that interfere with their functioning, whereas people with OCPD are highly functioning individuals who are convinced that their way of thinking is absolutely correct, if not superior to everyone else's.

"OCD, in contrast to OCPD, often paralyzes people," Kendall told LiveScience. "Someone with OCD may have trouble working at all, because he might spend hours every day scrubbing his hands to make sure that they are perfectly clean. That person won't have the energy to start Apple or to fly across the Atlantic on a piece of wood like Charles Lindbergh." [The 10 Most Controversial Psychiatric Disorders]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Jobs, Lindbergh and other high-fliers are the subject of Kendall's recent book, "America's Obsessives: The Compulsive Energy That Built a Nation" (Grand Central Publishing, 2013). The book is filled with examples of people (mostly men, as OCPD is less common among women) who rose to the top of their fields, largely due to their obsessiveness.

A long history of obsessives

Thomas Jefferson — architect, botaanist, diplomat, farmer, meteorologist, president and author of the Declaration of Independence — also kept a written log of every penny he ever spent and charted every vegetable market in the Washington, D.C., area, according to Kendall.

Baseball legend Ted Williams of the Boston Red Sox also exhibited the traits of OCPD, Kendall said. "When I wasn't eating or sleeping, I was practicing my swing," Williams famously said. He also approached the practice of hitting a baseball as a science, even attending physics lectures at MIT to better understand the dynamics of swinging a bat.

But single-mindedness like this comes at a dear cost — one that's generally paid by other people. "Obsessives tend to miss out on the joys of family life. They have a hard time connecting with others," Kendall said "They are control freaks who are uncomfortable unless they are in a dominant position in a relationship." Indeed, Jobs refused all contact with his biological father, who tried in vain to reconnect with his famous son.

The annals of history are filled with successful, obsessive people who cultivated rich, benevolent public personas, but had private lives that bordered on monstrous. "Lindbergh kept detailed checklists on the so-called infractions of his sons and daughters. He would record every incident of gum-chewing," Kendall said. [7 Personality Traits You Should Change]

Slugger Williams, who championed cancer treatment on behalf of the Dana-Farber Cancer institute in Boston, once admitted that he was "horses**t" to his own neglected children.

Perhaps no one personifies this dichotomy better than Jobs, whose achievements could make his life story read like a hagiography (he was a rags-to-riches electronics wizard, a Zen Buddhist and a billionaire). But behind the scenes, he reportedly could be impossible to relate to on a human level.

"Jobs was difficult to work for," Kendall said, "and would often blow his stack when something wasn't done the right way," which meant, of course, his way.

"And his difficult personality was the reason for his hiatus from Apple in the 1980s," Kendall said. Suffering from a bad reputation earned by his heavy-handed, mercurial management style, Jobs was forced out of Apple in 1985 (he rejoined the company in 1996).

There's some evidence that Jobs — who was never actually diagnosed with OCPD (Kendall asserts that he's simply suggesting the diagnosis, based on current criteria) — also had an eating disorder that's frequently associated with OCPD. "He struggled on and off with anorexia, a condition that is also associated with a history of trauma in childhood," Kendall said. "While Steve Jobs was lucky that his adoptive parents were kind, he seems to have possessed some scars from the adoption."

"A harsh early life seems to be a common theme in the icons whom I studied," Kendall explained. "Ted Williams was neglected by both his parents, neither of whom was around much when he was a kid. He ended up bonding with his bat rather than with other people."

The benefits of mental illness

There's a large and growing body of research devoted to the link between successful, high-achieving personalities and some degree of mental illness. For instance, a few personality traits of psychopaths may actually be positive in some circumstances, according to researcher Scott Lilienfeld, a psychologist at Emory University in Atlanta.

Lilienfeld found that a couple of psychopathic traits are, ironically, also linked to heroic behavior. A psychopathic trait called fearless dominance — essentially boldness — was linked with greater heroism and altruism toward strangers.

"Personality traits can be good or bad depending on the person and depending on the situation and also how they're channeled," Lilienfeld told LiveScience in an earlier interview.

"Fortunately, obsessives aren't as dangerous as psychopaths — they don't kill anyone — but they can be destructive," Kendall said. "Obsessionality is part of the way [up] on the psychopath continuum. And we need to realize that just because someone is successful doesn't necessarily mean that he or she is totally sane or even reasonable … Sometimes a person rises to the top precisely because he is a tad mad."

Obsessives and human civilization

There's even some evidence that OCPD may have helped human civilization evolve: A 2012 report in the journal Medical Hypotheses presented the "ADHD-OCPD theory of human behavior," which states that people with attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder and OCPD were critical in the switch from a hunter-gatherer society to an agricultural society.

Farmers, the theory proposes, who were more meticulous, detail-oriented perfectionists would have been more successful than others, especially when growing just one crop (only corn, for example). Being more successful, these obsessive individuals would have had more children, and their successful traits would have thus spread to other fields, giving rise to merchants, teachers, doctors and other specialists.

There are positions, it seems, in which people with OCPD naturally shine, Kendall asserts. "Obsessives do very well in the IT world. In fact, tech firms such as SAP are now making a concerted effort to hire workers who have Asperger syndrome, which is an analogous condition," Kendall said. "They also do well in athletics, particularly in sports such as baseball or golf in which they need to do the same thing over and over again — such as swing and hit the ball."

But the obvious talents of these individuals don't make them perfect for every task. "Since they lack people skills, they should stay away from jobs that require sensitive interaction with others," Kendall said. "For example, an obsessive would be a disaster as the head of an HR [human resources] department."

The key, then, is playing to the strengths of people with OCPD, while minimizing their limitations, Kendall said. "The challenge for obsessives — and perhaps for everyone, as most of us have a touch of something — is to find a way to channel constructively their passions."

Follow Marc Lallanilla on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.