NASA Telescope May Hunt for Rocky Mars-Size Planets Around 'Failed Stars'

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope could be used to find Mars-size alien planets orbiting strange "failed stars" known as brown dwarfs, according to a new proposal by a multinational astronomy team.

The group, led by a postdoctoral researcher at MIT, proposes to use the venerable observatory to find small, rocky exoplanets around brown dwarfs, which are larger than planets but too small to ignite the nuclear fusion reactions that power stars.

Astronomers will seek planets crossing the face of these brown dwarfs, in the hopes that some of them will end up being capable of supporting life as we know it. [9 Exoplanets That Could Host Alien Life]

The planets sought would orbit more closely than Mercury does to the sun, but the faint warmth of brown dwarfs could still make such inner regions habitable, researchers said.

"Our program represents an essential step towards the atmospheric characterization of terrestrial planets and carries the compelling promise of studying the concept of habitability beyond Earth-like conditions," the team's paper stated.

Spotting small planets around brown dwarfs

The team is aiming for Mars-size planets because of their importance in planetary formation models, lead author Armaury Triaud told SPACE.com.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

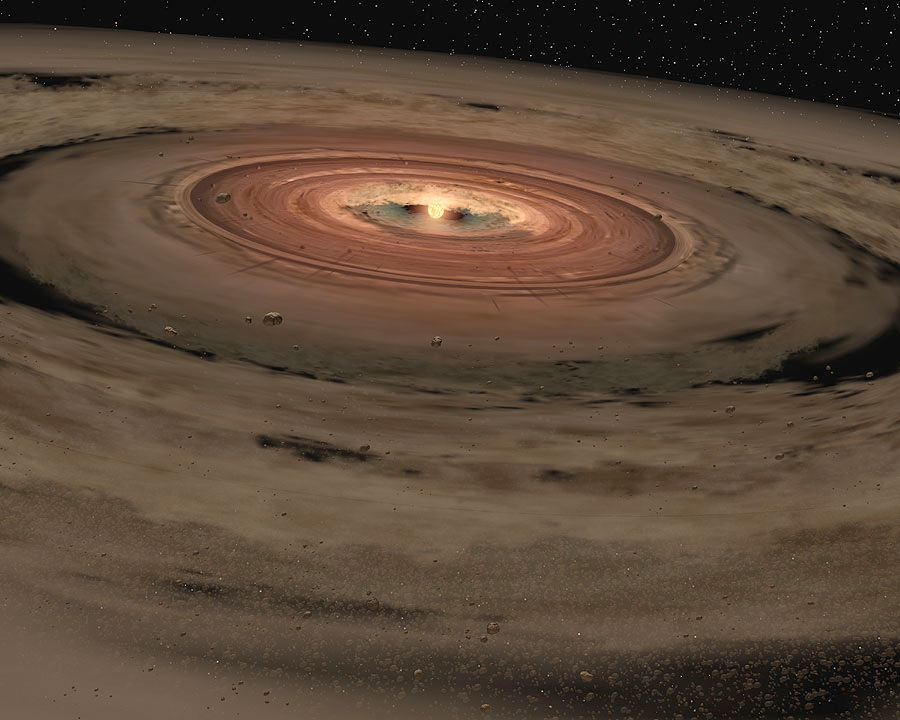

Models suggest our solar system emerged from a spinning disk of dust and gas, with planets slowly clumping together as particles collided, Triaud said, cautioning that we can't be completely sure of what actually occurred.

Our nascent solar system crossed an important threshold when those protoplanets reached the size of Mars, he said.

"Eventually these planet embryos, the size of Mars, those would collide and form bigger rocky planets, or the core of [gas giant] planets such as Jupiter," Triaud said.

It would be easier to spot such small, rocky worlds around a brown dwarf than a larger star, he added. Brown dwarfs are brighter in the infrared – the wavelength in which heat radiates – and those we can see are relatively close to Earth, making it easier to detect the effect of any planets on their motions.

Spitzer's data on planets could then be used by the forthcoming James Webb Space Telescope. James Webb should be able to probe planetary atmospheres, possibly to search for "biomarker" molecules such as oxygen, Triaud noted, although the orbiting observatory would need to stare at the planet for a long time.

"Right now, there are no projects able to find an Earth-sized planet whose atmosphere can be studied with the James Webb," he said. "Our project is the only path."

Short orbits, lots of data

In a brown dwarf's "habitable zone" — the range of distances in which liquid water could exist on a world's surface — it's possible that a planet could pass between the brown dwarf and Earth more than 50 times a year, providing ample opportunity for the science team to conduct observations.

"Our simulation shows that with only 50 occultations, you'll be able to reliably detect the atmosphere of a planet. It's 50 years, in a sense, of research."

The same data, Triaud noted, would be useful for studying brown dwarfs themselves — specifically their rotations and what happens in their atmosphere.

The team's paper, which is a portion of an observing proposal made for NASA, is available on the online preprint site Arxiv.org.

Triaud said the proposal is being considered, along with many others, as cases to further extend Spitzer's mission. If the extension is accepted, his team's proposal will compete against those of others for valuable telescope time.

Spitzer launched in August 2003. It ran out of coolant four years agobut is observing new targets (such as near-Earth objects) as part of an extended mission.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

Elizabeth Howell was staff reporter at Space.com between 2022 and 2024 and a regular contributor to Live Science and Space.com between 2012 and 2022. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus