Perfectly preserved 310 million-year-old fossilized brain found

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Researchers have uncovered a never-before-seen fossilized brain from a 310 million-year-old horseshoe crab, revealing some surprises about the evolution of these wannabe crustaceans, according to a new study.

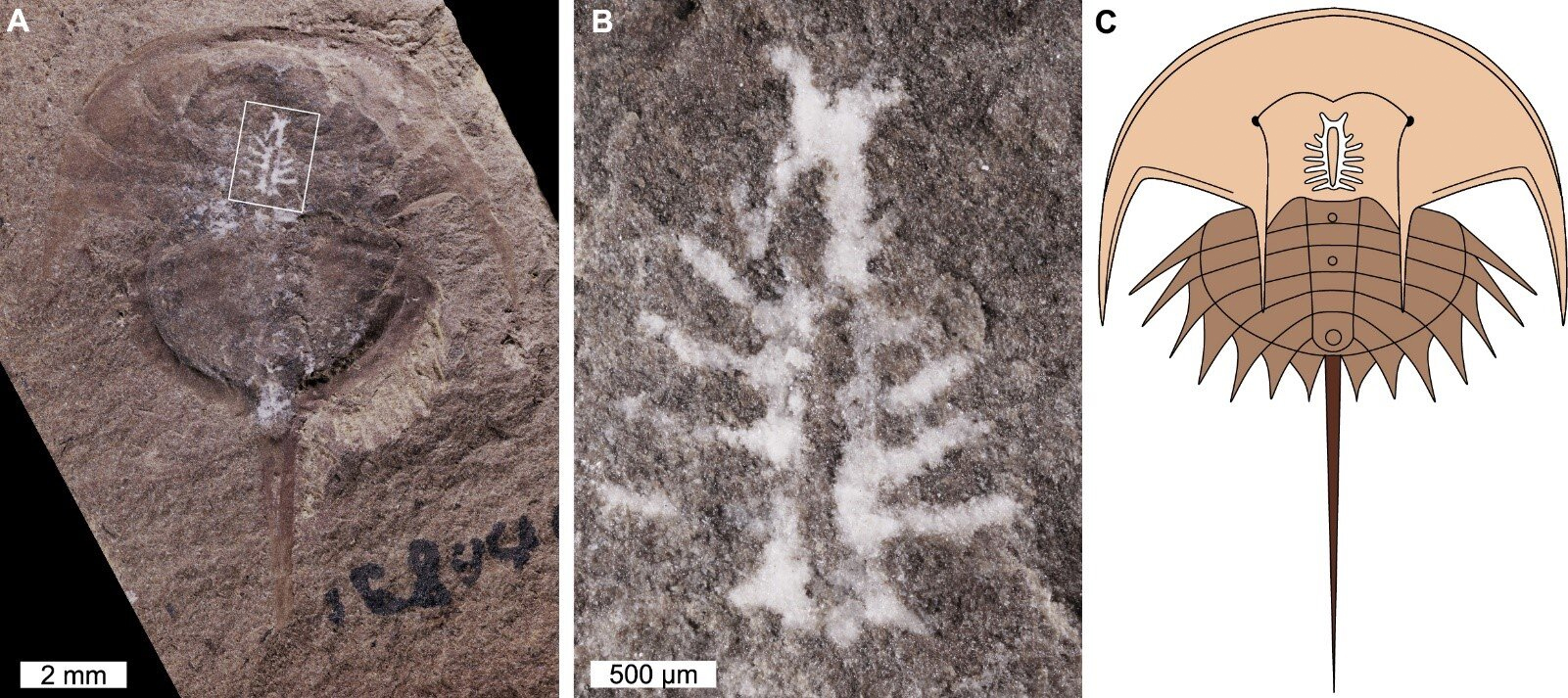

The fossilized brain, which belongs to the extinct species Euproops danae, was discovered at Mazon Creek in Illinois, where the conditions were just right to perfectly preserve the animal's delicate soft tissue.

There are four species of horseshoe crabs alive today — all of which sport hard exoskeletons, 10 legs and a U-shaped head. Despite their name, these "crabs" are actually arachnids that are closely related to scorpions and spiders, according to The National Wildlife Federation. Although horseshoe crab fossils are relatively common, nothing was previously known about their ancient brains, the researchers said.

Related: From dino brains to thought control — 10 fascinating brain findings

"This is the first and only evidence for a brain in a fossil horseshoe crab," lead author Russell Bicknell, a paleontologist at the University of New England in Maine, told Live Science. The chances of finding a fossilized brain are "one in a million," he added. "Although, even then, chances are they are even rarer."

Soft tissues that make up brains are very prone to rapid decay, Bicknell said. "In order for them to be preserved, either very special geological conditions, or amber, are needed."

In this case, geology helped to keep the soft tissue in tip-top condition over the years and preserve the brain — or at least a copy of the brain. "We have a mold of the brain, not the brain itself, so to speak," Bicknell said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The deposits at Mazon Creek are made of an iron carbonate mineral called siderite, which forms concretions — mineral precipitations — that can quickly encase a dead body and fossilize it. Although such concretions preserved the horseshoe crab's body, the brain tissue still decomposed and eventually disappeared. However, as the brain rotted away it was replaced by a clay mineral called kaolinite, which created a cast of the brain.

Kaolite is white in color, whereas siderite is dark gray. This color contrast meant the brain fossil "stood out more than it would have normally" from the rest of the fossil, Bicknell said.

The hunt is now on for more ancient brains that might have been fossilized in the unique geological conditions that preserved this horseshoe crab.

"The Mazon Creek deposit is exceptional," Bicknell said. "If we started looking, we may be lucky enough to find more [brain fossils]."

The discovery provided researchers with the unique opportunity to study how the arachnids' brains evolved over time. But to the researchers' surprise, they found that the ancient brain, which dates to the Carboniferous period (359 million to 299 million years ago), was remarkably similar to that of a modern horseshoe crab.

"Despite 300 million years of evolution, the fossil horseshoe crab brain is pretty much the same as modern forms," Bicknell said.

The study was published online July 26 in the journal Geology.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus