'Impossible' Stars Found in Super-Close Orbital Dances

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

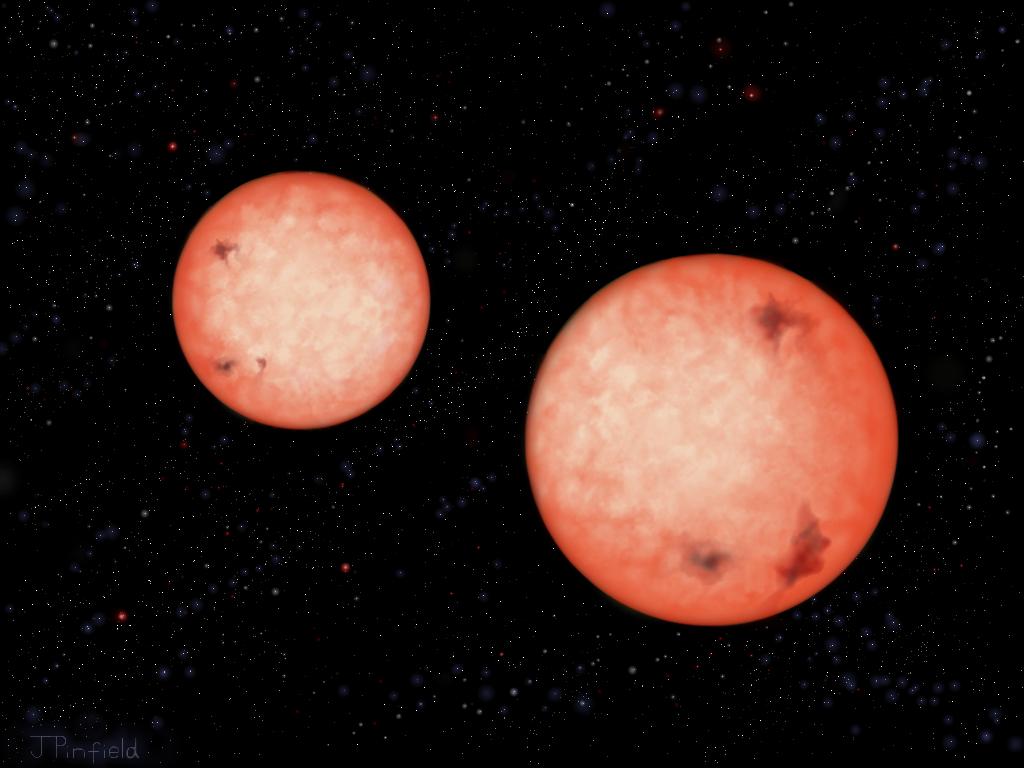

Four pairs of what astronomers are calling "impossible stars" — stellar twins in orbits so close they defy explanation — have been found in our Milky Way galaxy, scientists say.

Astronomers using the United Kingdom Infrared Telescope (UKIRT) in Hawaii discovered the four star pairs, each of which is a binary system in which two stars circle each other in less than four hours. Until now, scientists thought that such twin-star setups couldn't exist.

Our sun does not orbit another star, but roughly half of the stars in our Milky Way galaxy do, as part of a binary system. These binary stars likely formed close together, and have been orbiting one another since their birth, the researchers said.

It was typically thought that if a star formed too close to another, the two stars would quickly merge into a single, bigger star. This theory seemed to agree with observations taken over the last three decades, which reveal that binary systems are abundant, but none of the pairs have an orbital period shorter than five hours, the researchers said.

In the new study, a team of astronomers monitored the brightness of hundreds of thousands of stars in near-infrared light over the past five years, and found several stellar binaries with surprisingly short orbits. [Top 10 Star Mysteries]

The astronomers focused on binaries of red dwarfs, which are stars that are up to ten times smaller and a thousand times dimmer than the sun. While red dwarfs are the most common type of star in the Milky Way galaxy, they often do not show up in astronomical surveys because they are too dim in visible light.

"To our complete surprise, we found several red dwarf binaries with orbital periods significantly shorter than the 5 hour cut-off found for sun-like stars, something previously thought to be impossible," the study's lead author Bas Nefs, from Leiden Observatory in the Netherlands, said in a statement. "It means that we have to rethink how these close-in binaries form and evolve."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Early in their lifetimes, stars shrink in size, which suggests that the orbits of stars in these tight binary systems must have also shrunk since they were formed, the researchers said. If not, the stars would have interacted with each other early on, and would have likely merged.

But, how the orbits of stars in these binaries shrunk by so much remains a mystery. According to the new study, one possible explanation is that cool stars in binary systems are much more active and violent than was previously thought.

As the cool stellar companions spiral in toward each other, their magnetic field lines may become twisted and deformed. This powerful magnetic activity may help slow down the spinning stars, allowing them to move closer together, the researchers explained.

"The active nature of these stars and their apparently powerful magnetic fields has profound implications for the environments around red dwarfs throughout our galaxy," study co-author David Pinfield, from the University of Hertfordshire in England, said in a statement.

Detailed results of the new study appear in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow SPACE.com on Twitter @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus