Rest Your Fears: Big Earthquakes Not on the Rise

SAN FRANCISCO — While Earth seems to be getting slammed with frequent mega- earthquakes lately, big quakes are not on the rise.

That's the message from two studies presented here this week at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union. Two research teams using different statistical methods both found that the global risk of big earthquakes is not higher than usual. Neither team found any evidence that big earthquakes can trigger other big earthquakes over long distances.

"We tend to see patterns in random processes, that's just something we do," said Andrew Michael, a U.S. Geological Survey scientist who presented his work Wednesday (Dec. 7). "In particular, people expect when something's random for it to be uniformly spread out, but, in fact, really random processes have a lot of clustering in them."

That clustering can make it look like there are patterns in the short term, Michael said, even when the long-term statistics don't show any meaningful variation.

The rate of big earthquakes

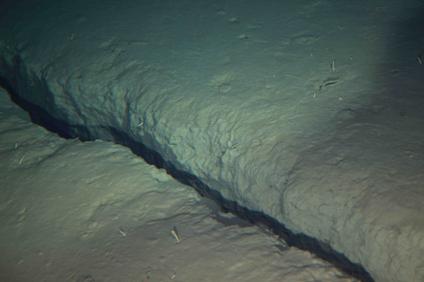

On a local level, earthquakes do cluster and trigger one another, with a main shock often surrounded by fore- or aftershocks. But whether large earthquakes that occur thousands of miles across the globe from each other are related is a separate question.

In research presented Monday (Dec. 5), University of California San Diego geophysicist Peter Shearer and UC Berkeley statistician Philip Stark reported that the recent rate of magnitude-7.5 to magnitude-8 quakes is close to its historical average. Since 2004, magnitude-8 quakes have been more common than usual, the researchers reported, but this blip is consistent with normal variation, the researchers reported.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Such giant earthquakes are expected to occur at least once during the 111-year history of the catalogue of quake data, they said.

Random patterns

In a second study, the USGS's Michael used three statistical methods to find out if large earthquakes cluster together or if what looks like clusters is just random variability. A first glance at global earthquakes since 1900 does look very clustered, he said. But as soon as you remove aftershocks from the equation, that pattern disappears.

"That tells us that all the clustering we were seeing on the global scale was just an effect of local clustering," Michael told LiveScience.

Michael also looked at time periods after a large quake to see if other large quakes peaked in the following months and years. Again after removing direct aftershocks, he found no such evidence. A third test again failed to uncover evidence of clustering.

"Really, if you take any data set and you look for patterns in it and you insist on things happening in a very similar way, things will always look very surprising," he said. "Even in random sequences you can sort of define yourself into a corner where things seem unique."

The risk of earthquakes hasn't gone down either, Michael warned, and people living near areas where large quakes have hit should keep their guard up. Aftershocks to giant quakes like the March 2011 Tohuko quake in Japan can be very large themselves, he said.

"There is localized higher risk," he said. "There just isn't global higher risk."

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.