Japan Quake May Have Struck Atmosphere First

The devastating earthquake that struck Japan this year may have rattled the highest layer of the atmosphere even before it shook the Earth, a discovery that one day could be used to provide warnings of giant quakes, scientists find.

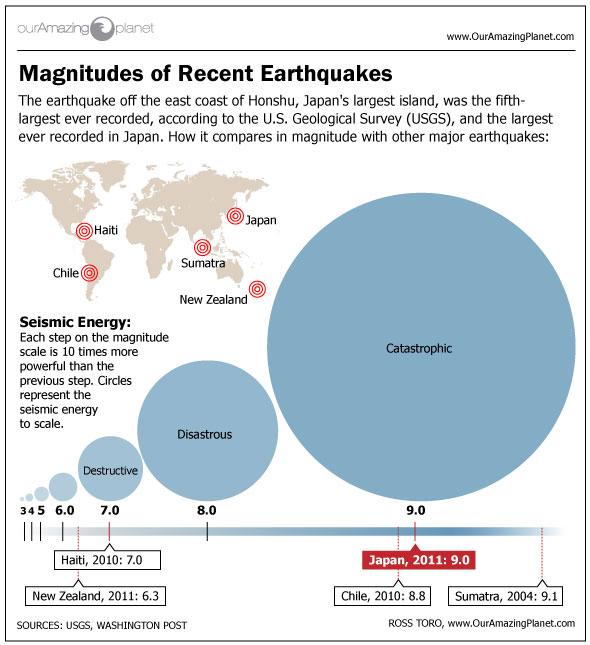

The magnitude 9.0 quake that struck off the coast of Tohoku in Japan in March ushered in what might be the world's first complex megadisaster as it unleashed a catastrophic tsunami and set off microquakes and tremors around the globe.

Scientists recently found the surface motions and tsunamis this earthquake generated also triggered waves in the sky. These waves reached all the way to the ionosphere, one of the highest layers of the Earth's atmosphere.

Now geodesist and geophysicist Kosuke Heki at Hokkaido University in Japan reports the Tohoku quake also may have generated ripples in the ionosphere before the quake struck.

Disruptions of the electrically charged particles in the ionosphere lead to anomalies in radio signals between global positioning system satellites and ground receivers, data that scientists can measure.

Heki analyzed data from more than 1,000 GPS receivers in Japan. He discovered a rise of approximately 8 percent in the total electron content in the ionosphere above the area hit by the earthquake about 40 minutes before the temblor. This increase was greatest about the epicenter and diminished with distance away from it.

"Before finding this phenomenon, I did not think earthquakes could be predicted at all," Heki told OurAmazingPlanet. "Now I think large earthquakes are predictable."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Analysis of GPS records from the magnitude 8.8 Chile earthquake in 2010 revealed a similar pattern, Heki said. These anomalies also may have occurred with the Sumatra magnitude 9.2 earthquake in 2004 and the magnitude 8.3 Hokkaido earthquake in 1994, he added.

If true, further research could lead to a new type of early-warning system for giant earthquakes.

The anomaly is currently seen before earthquakes only with magnitudes of about 8.5 or larger, Heki cautioned. Still, if researchers can detect what specifically causes this ionospheric phenomenon, it also might be possible to detect precursory phenomena for smaller earthquakes, he said.

Heki did caution that the ionosphere is highly variable — for instance, solar storms can trigger large changes in total electron content there. Before researchers could develop an early-warning system for earthquakes based on ionospheric anomalies, they would have to rule out non-earthquake causes.

Heki detailed his findings online Sept. 15 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

This story was provided by OurAmazingPlanet, sister site to LiveScience.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus