Evidence Builds For Water on Mars

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

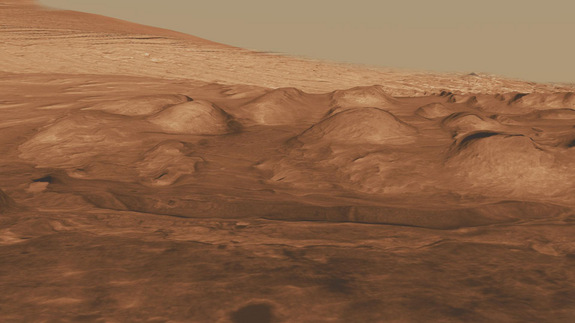

NASA has chosen a landing site for its next Mars rover with the goal of seeking more signs of historical water on the planet, and a recent study suggests it may find it.

New evidence of Mars' watery past has surfaced, NASA scientists say, suggesting that telltale signs of the wet stuff may lurk under thin layers of rust seen scattered around the Red Planet, in areas that mirror conditions found in Earth's desert regions.

That's good news for NASA' Mars Science Laboratory Curiosity rover, which will be launched toward the planet later this year. The rover will land in Gale Crater, the space agency announced Friday (July 22), in part because the site offers promising conditions for the search for signs of water. [Mars Explored: Landers and Rovers Since 1971 (Infographic)]

Scientists have long known that Mars is home to a few patches of carbonates — minerals that form readily in large bodies of water and can point to a planet’s wet history — yet they suspect that many more carbonates may be hidden beneath the rust (iron oxide) that coats many regions of the planet.

"It's possible that an important clue, the presence of carbonates, has largely escaped the notice of investigators trying to learn if liquid water once pooled on the Red Planet," said Janice Bishop, a planetary scientist at NASA's Ames Research Center at the SETI Institute at Moffett Field, Calif., in a statement.

"The plausibility of life on Mars depends on whether liquid water dotted its landscape for thousands or millions of years," said Bishop, the lead author on a paper published in the July 1 online edition of the International Journal of Astrobiology. [5 Bold Claims of Alien Life]

Scientists conduct field experiments in desert regions because the extremely dry conditions are similar to Mars. Researchers realized the importance of the varnish earlier this year when Bishop and Chris McKay, a planetary scientist at Ames, investigated carbonate rocks coated with iron oxides collected in the Mojave Desert.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

When the scientists examined the rusty varnish in the lab, they found it had tinkered with the spectral signature of carbonates hidden underneath.

In addition, McKay found dehydration-resistant blue-green algae under the rock

varnish. Scientists believe the varnish may have extended temporarily the time that Mars was habitable, as the planet's surface slowly dried up.

"The organisms in the Mojave Desert are protected from deadly ultraviolet light by the iron oxide coating," McKay said. "This survival mechanism might have played a role if Mars once had life on the surface."

NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) spacecraft found patches of carbonates, approximately 200 to 500 feet (60 to 150 meters) wide, on the Martian surface, yet the Mojave study suggests more patches may have been overlooked because their spectral signature could have been changed by the planet's pervasive rusty coating.

In fact, the rusty varnish is so widespread that NASA's Mars Exploration Rovers, Spirit and Opportunity, were equipped with motorized grinding tools to remove the rusty overcoat on rocks before other instruments could inspect them.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, sister site to LiveScience. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus