New Potions to Clean Old Masterpieces

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

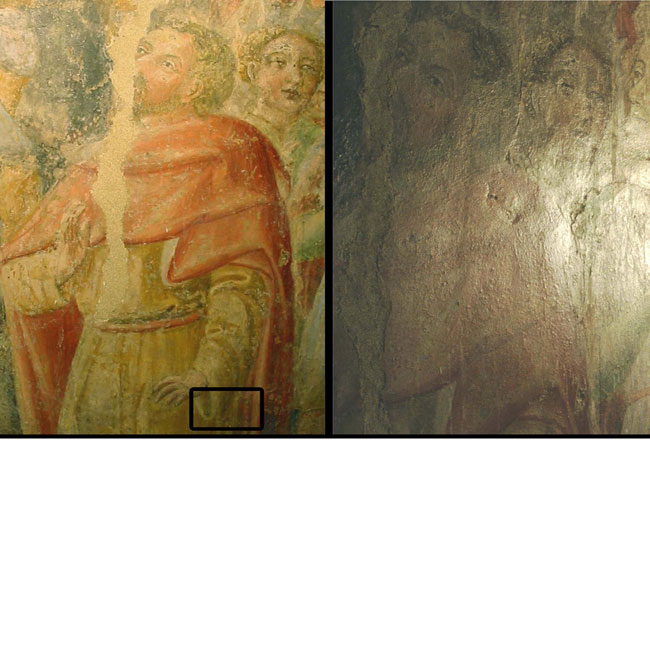

The delicate frescoes of the Renaissance master Lorenzo di Pietro "il Vecchietta" have survived for more than five centuries in the millennium-old Santa Maria della Scala in Siena, Italy, one of the oldest hospitals in Europe, but ironically, failed conservation efforts to save them might have destroyed them instead. Now advanced potions much like salad dressing that were developed by scientists in Italy could help cleanse masterpieces from hundreds of years of grime and the accidental harm wrought by prior attempts to restore or preserve them. Art, like artists, often suffers, especially after long centuries of tarnishing , deluge and flame. Unfortunately, some techniques designed some 50 years ago to conserve works of art have now been found to degrade as they age. In the case of Vecchietta's frescoes, the polyacrylate resin used to conserve the paintings darkened their colors and contributed an unwelcome reflective glare. Physical chemist Piero Baglioni at the University of Florence and his colleagues first employed salad-dressing-like formulations to conserve art two decades ago, when he was asked to help clean Renaissance paintings in Florentine churches of wax that had dripped on them. Salad dressing is essentially a mix or emulsion of oil and water. The micro-emulsions Baglioni and his collaborators used to extract the contaminants from the art were adapted from an emulsion used to pull extra petroleum from oil fields. Now Baglioni and his colleagues have invented micro-emulsions that are far better and less toxic than before. The key is a sugar-like compound that wraps an oily cleanser in tiny droplets less than a tenth of a wavelength of visible light in size. Altogether, these drops possess a tremendous amount of surface area to clean with, making the micro-emulsion ferocious at scrubbing away grime and polyacrylate resin. This means far less of the cleanser is needed than before, "so it's much safer, and you won't, say, contaminate an entire church with it," Baglioni told LiveScience. The researchers first pour the micro-emulsion onto cellulose fibers to make a paste. They next envelop artwork in super-thin Japanese paper and coat the wrapped-up art with the paste. After 10 minutes to a few hours, the paste is removed and the painting is cleansed. So far, Baglioni and his colleagues have used their new micro-emulsion to clean polyacrylate off Vecchietta frescoes. They also removed tar-like deposits from a 17th century fresco in Florence that was damaged during the 1966 flooding of the Arno River, as detailed in the May 22 issue of the journal Langmuir. The micro-emulsion will next get used to clean artwork in Sweden later this month. "We don't charge anything for it, Baglioni said. "We provide it basically for free."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus