First Jaws? Ancient Creature Sported One Scary Mouth

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Strange fusions of tooth-covered lips, tongues and throats in ancient eel-shaped creatures might reveal how jaws evolved, researchers now suggest.

The origin of jaws remains largely an enigma. To solve this mystery, scientists analyze jawless vertebrates (animals with backbones) both living and fossil.

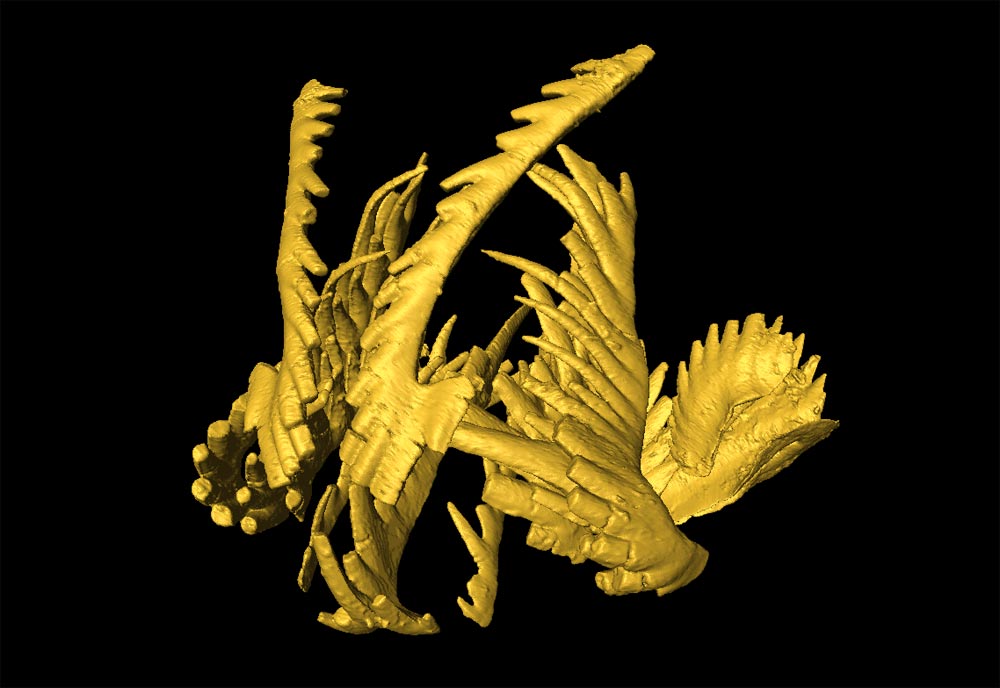

Investigators focused on extinct eel-like creatures known as conodonts, whose relationship with the vertebrate family tree is still a bit murky. Using X-rays of exceptionally well-preserved 250-million-year-old mouthparts of the conodont Novispathodus unearthed in southern China, they created 3-D models of how their mouths might have worked and compared this with research on other conodonts. [Image of 3-D mouth model]

The mouths that emerged might look monstrous by our standards. Apparently, most conodonts had two upper lips that each possessed a long, pointed, fang-like tooth. They also had a "tongue" of sorts that possessed a complicated set of spiny or comb-like teeth, an organ connected by pulley-like cartilage to two sets of muscles. In addition, its pharynx, or back of the throat, had two or more pairs of robust, sometimes molar-like, "teeth."

To eat, the creatures likely used their lips and "tongue" to grasp food. The "teeth" in their pharynxes then crushed or sliced up their meals, explained researcher Nicolas Goudemand, a paleontologist at the University of Zurich in Switzerland. [The Creatures of Cryptozoology]

As bizarre as this arrangement might sound, modern lampreys and hagfish have somewhat similar mouths, although they lack teeth in their pharynx, and their tongues have "teeth" made of horn as opposed to minerals. Actually, in this regard, "conodonts are closer to us than lampreys are," Goudemand told LiveScience, as our teeth are also made using minerals. "They were probably also grown in a similar way."

These findings suggest conodonts are vertebrates, and potentially the ancestors of the first jawed vertebrates. Although jaws evolved much earlier than Novispathodus — sharks date back at least 200 million years before these specimens — jaws likely evolved from even older creatures with similar pulley-like cartilage systems and mineral teeth.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The common ancestor of conodonts and lampreys — that is, some of the first vertebrates — must have had a similar pulley-like feeding mechanism," Goudemand said.

The scientists detailed their findings online today (May 9) in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus