25 grisly archaeological discoveries

A tragic sacrifice

Mountaineers climbing near Aconcagua in Argentina in 1985 stumbled across a dark memento of the past. Nestled in a stone structure was the huddled mummy of a 7-year-old who died about 500 years ago.

The little boy was the victim of child sacrifice. The ritual was called capacocha, and it was practiced by the Inca people. As in "The Hunger Games," children were called as tribute from rural regions to the city of Cuzco, where they would live for about a year before they were drugged and walled into their tomb to die of exposure. Many of the mummies sport skull fractures, so there is debate over how they were killed. They may have been knocked out in order to decrease their suffering, archaeologists say.

Collective punishment

You work for years, supporting the first female emperor to China and smoothing her rise to power. You break your own arm instead of fighting against her for a rebel army. You help her mollify civil disorder.

And then your little brother goes rogue and gets you all executed.

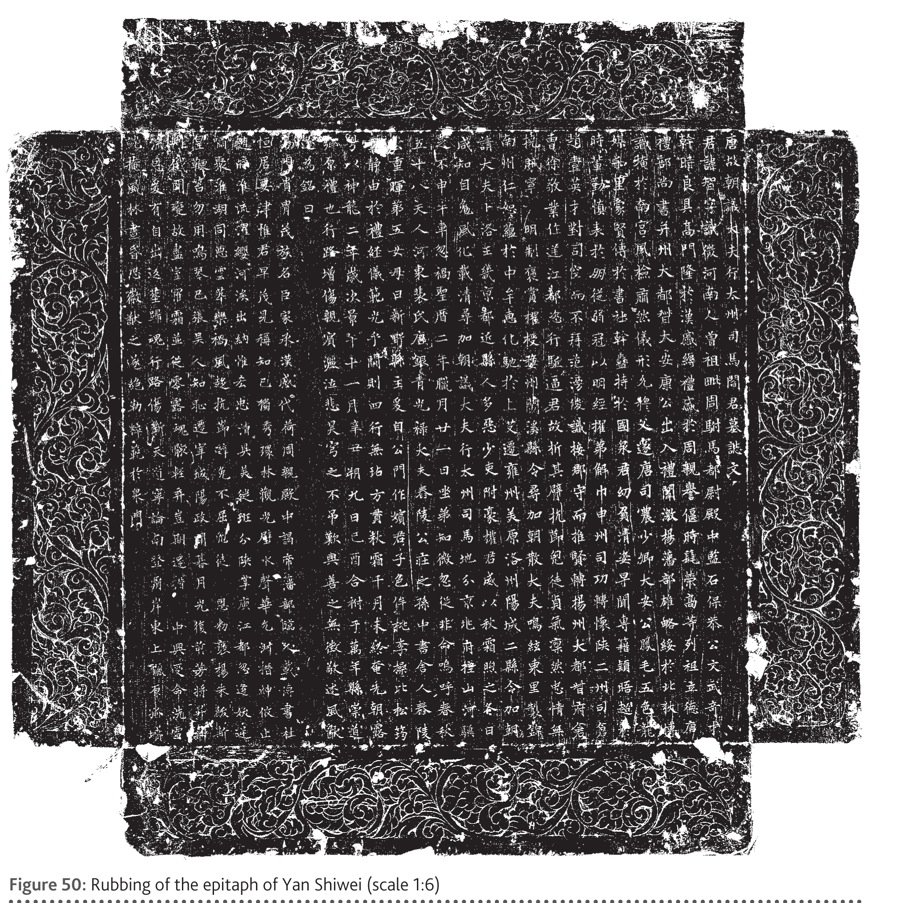

That's the sad story of Yan Shiwei, one of the favorite officials of Wu Zetian, the founder of China's Zhou dynasty. Archaeologists uncovered Yan Shiwei's 1,300-year-old tomb and discovered the tale on a stone-inscribed epitaph. Yan Shiwei's little brother, Yan Zhiwei, turned against Wu Zetian around 699. As a collective punishment, the entire family was executed and, according to the carvings, "carelessly buried."

Bones in a tree

A season 6 episode of the crime show "Bones" involves the case of a skeleton discovered with a dogwood tree growing through it. Something similar really happened in Ireland — though the tree was a beech.

In 2015, a 215-year-old tree blew over in a winter storm in Collooney, Ireland. Entangled in the roots was a mass of bones. They turned out to belong to a boy who died between the year 1030 and 1200. Making the discovery all the more creepy, the boy's ribs and hands showed knife marks, suggesting that his death was violent.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Ancient cold case

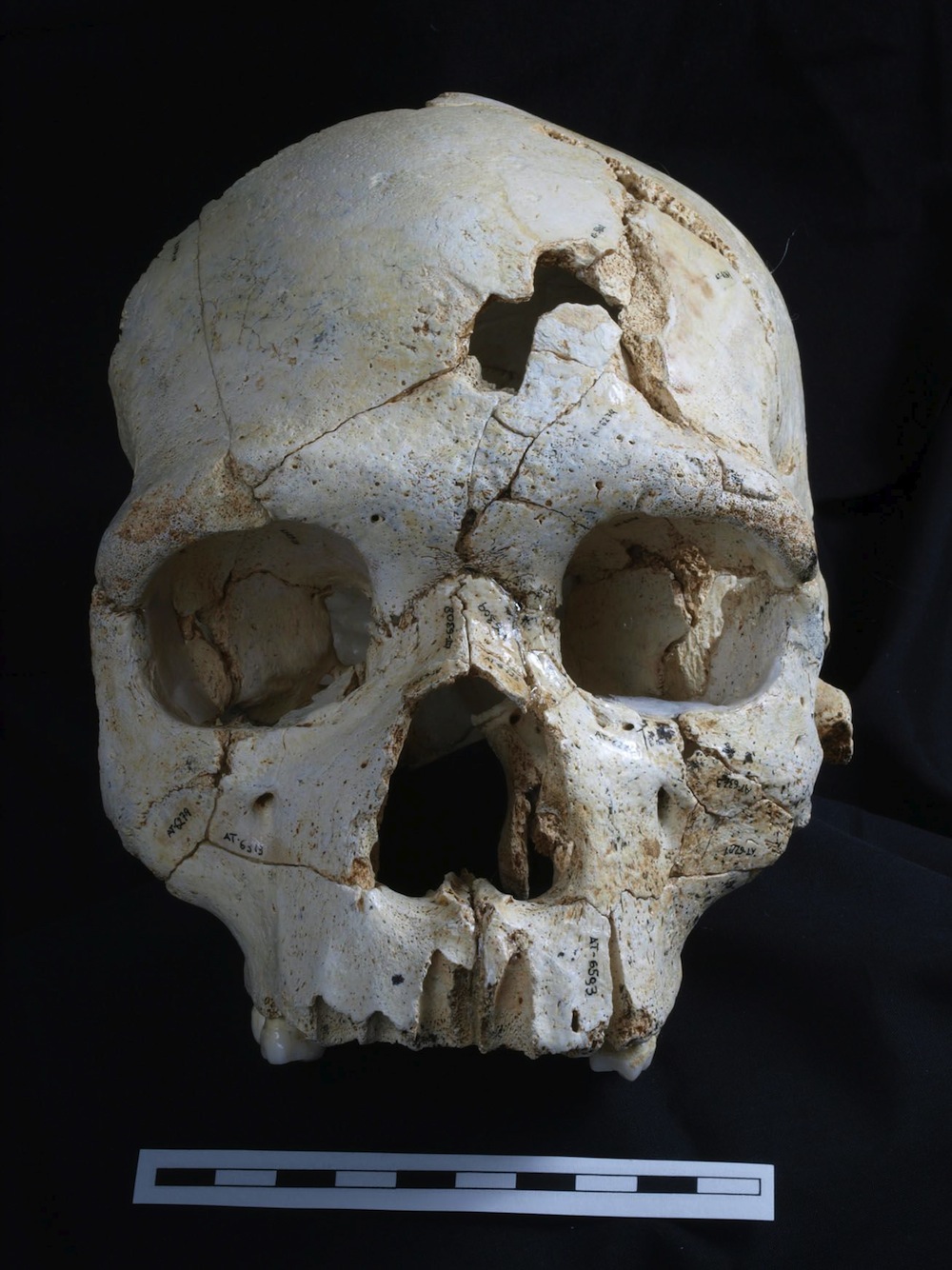

Skull fractures on a 430,000-year-old skeleton found in a Spanish cave point to a likely cause of death: murder most foul.

The victim's remains were found in a cave in the Atapuerca mountains, along with bones from 28 individuals of various Homo species. The bodies seem to have been moved there on purpose, making this spot possibly one of the oldest burial grounds ever found.

The sex and even species of the murder victim remain unknown, but researchers think that the wounds found on the skull couldn't be explained either by a fall or by postmortem damage. The murder weapon may have been a spear or an ax, but it's safe to say that after 430,000 years, the suspect is not still at large.

Cannibalism in the Canadian Arctic

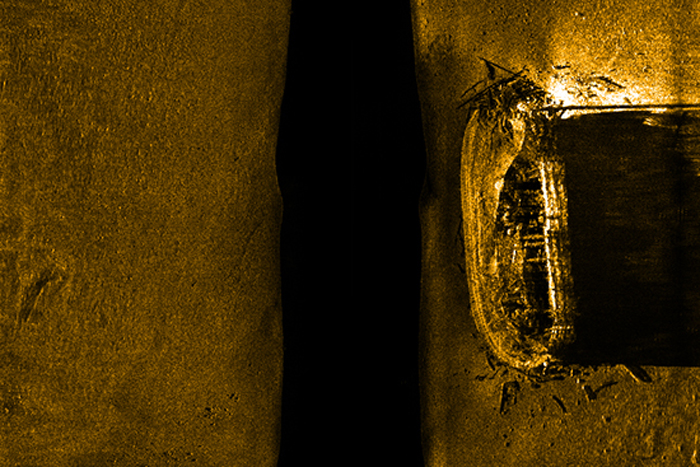

When Sir John Franklin and his crew headed off for their Arctic expedition in 1845, they hoped to navigate the Northwest Passage. They almost certainly did not expect that they'd be resorting to cannibalism within a few short years.

The Franklin expedition's two ships, the HMS Terror and the HMS Erebus, became trapped in ice … which failed to melt summer after summer. By April 1848, 24 men had died, and the remaining crew set off in an attempt to trek to the nearest trading post. None were ever heard from again.

Over time, the bones of some of the crew members were found. In 2015, researchers reported in the Journal of Osteoarchaeology that the bones had been hacked and boiled, and many were even cracked to get at the marrow inside. The discovery speaks to the very desperate situation in which those men found themselves," bioarchaeologist Anne Keenleyside of Trent University, who was not involved in the study, told Live Science. "You have to imagine yourself in that situation, what would you do?"

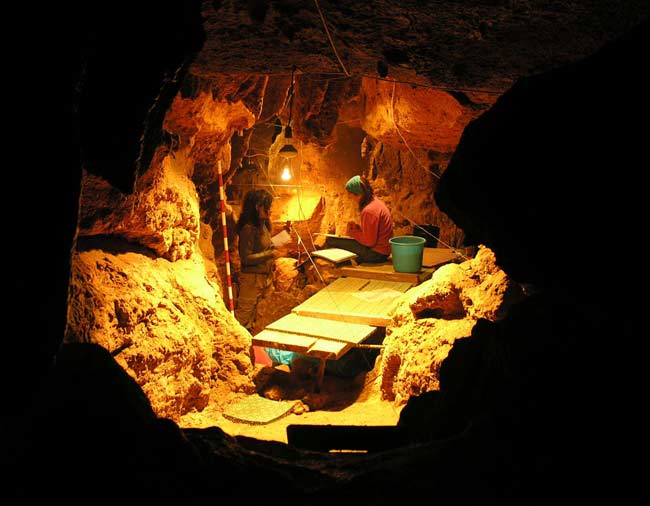

Neanderthal cannibals

Archaeology is the study of human society — but for our purposes, Neanderthals are close enough (we did interbreed, after all). In 2010, researchers reported the discovery of the skeletons of a family of Neanderthals in a cave in Spain. What makes the find so chilling is that the bones showed signs of cannibalism.

The three adult females, three adult males, three teenagers, two kids and an infant may have become a meal for another group of Neanderthals (humans weren't around in Europe at this time, so they're off the hook). This family isn't the only evidence of Neanderthal cannibalism, archaeologists said. It seems that when times got tough, Neanderthals weren't shy about chowing down on each other.

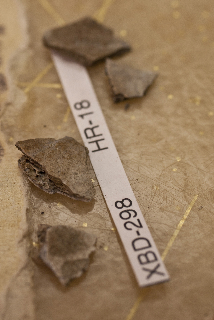

Burned Alaskan child

About 11,500 years ago, a 3-year-old child was burned and buried in a hearth in central Alaska. After the cremation, the home that housed the hearth was filled in and abandoned.

The lonely body — found as charred bone fragments still arranged as they were when the fire died — struck a nerve with its discoverers, University of Alaska archaeologist Ben Potter and dental anthropologist Joel Irish. Both researchers have children who are about the same age as the ancient Alaskan was when he or she died, Potter said.

"That was quite remarkable for both of us to be thinking, beyond the scientific aspect, that yes, this was a living, breathing human being that died," Potter said.

Tomb mystery

Buried, exhumed, burned and re-buried: That's the post-mortem fate of Alexander the Great's half-brother and successor, Philip III Arrhidaios, according to historical texts. The question is, have archaeologists found what was left of the man after his people got done with him?

A royal tomb in Greece containing the burned bones of a man and a young woman could be the resting place of Philip III and his young warrior-queen wife Eurydice, who were respectively killed and forced to commit suicide by Philip III's stepmother, Olympias, the mother of Alexander the Great. But some researchers argue that the entombed man is actually Philip II, Alexander the Great's dad. That would make the woman in the tomb Cleopatra, Philip II's last wife. (A different Cleopatra than the famous Egyptian queen, this Cleopatra nonetheless met a tragic end. She was either killed or forced to commit suicide by Olympias, whose bad side you didn't want to be on.)

The debate still rages as to whether the tomb is the final resting place of Philip II or Philip III. The most recent volley of scientific debate hinged on whether the bones were burned dry or covered in flesh and viscera.

Ill-fated expedition

The search for the legendary Northwest Passage claimed many lives, including those of 129 explorers who went searching for a sea route through the Arctic in 1845. Lead by British Rear-Admiral Sir John Franklin, the doomed crew headed into the icy unknown, where they would all perish of starvation, scurvy, hypothermia and exposure.

To make matters worse, many of the men's remains show evidence of lead poisoning, probably from the canned foods they were eating. High levels of lead in the body can cause vomiting, weakness and seizures.

At first, the dead received proper — if shallow — burials. Later on in the expedition as more explorers died, researchers say, bodies were left unburied, and some may have been cannibalized. Few bodies have been identified, despite attempts at facial reconstruction, as seen above.

Ancient Chemical Warfare

Ancient warfare was a messy matter, but a group of 20 or so Roman soldiers may have met a particularly nasty death nearly 2,000 years ago. During a siege of the Roman-held Syrian city of Dura, Persian soldiers dug tunnels under the city walls in an attempt to undermine them. The Romans retaliated by digging their own tunnels in an attempt to intercept the Persians. But the Persians heard them coming, and some archaeologists think they prepared a grisly trap: A cloud of noxious petrochemical smoke that would have turned the Romans' lungs to acid.

The tunnels were excavated in the 1920s and '30s, and have been reburied now. But some modern archaeologists think the placement of the skeletons and the presence of sulfur and bitumen crystals suggests chemical warfare. The choking gas would have been like "the fumes of hell," archaeologist Simon James of the University of Leicester told LiveScience.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus