Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Age: unknown. Sex: unknown. Cause of death: blunt force trauma. Time of Death: 430,000 B.C., give or take a few thousand years.

Archaeologists may have unearthed one of the world's oldest cold cases — a skull fragment found in a Spanish cave from an ancient murder victim whose head was bashed in.

The skull was first unearthed in the Atapuerca Mountains, which are threaded by a series of limestone caves, sinkholes and tunnels. In 1987, researchers scrambled down a chimney into one of those caves to discover a giant bone bed.

The site, known as Sima de los Huesos, or "pit of the bones," harbors thousands of skeletal fragments from at least 28 individuals from multiple Homo species, including Homo heidelbergensis and a mysterious Homo species known only as the Sima de los Huesos hominin. Scientists don't know exactly why so many bodies were buried in this region, but many have speculated that it is one of the world's oldest burial pits. [8 Grisly Archaeological Discoveries]

"The bodies were deposited at the site by other members of the social group," study co-author Nohemi Sala, a paleontologist at the Carlos III Health Institute in Madrid, speculated.

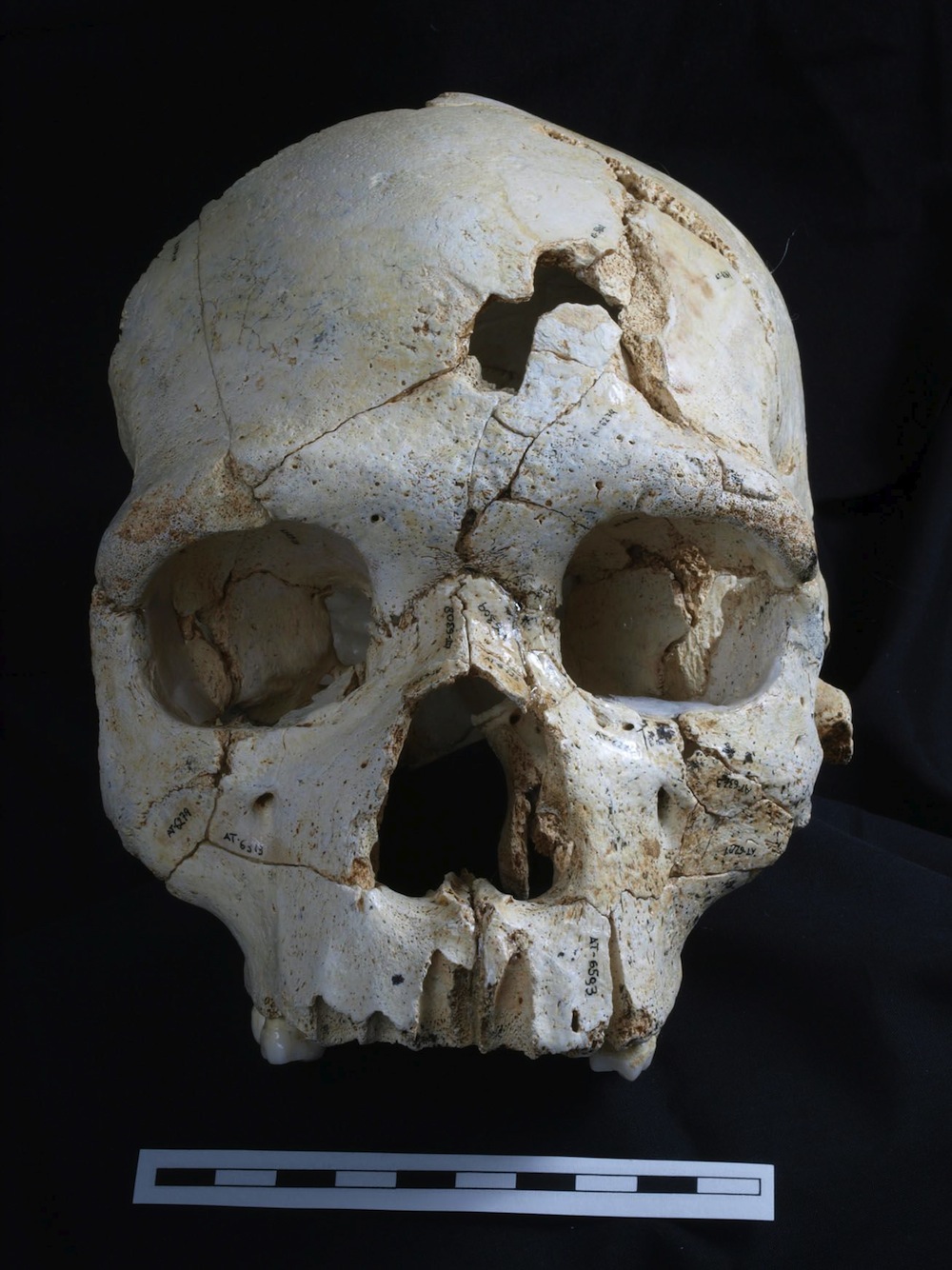

Scientists excavating at the site first found a skull fragment in 1990, but it wasn't until years later that they found other matching pieces of the skull. After many years, Sala and her colleagues painstakingly reconstructed the skull, revealing two holes poked through it. The skull belonged to a young adult of unknown sex and human species.

To solve this ancient murder mystery, the team analyzed the chemical makeup and structure of the bone around the holes, and found the head wounds had not healed before death, suggesting the man or woman died of his injuries.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

While it's possible that the "person" took a tumble down the chimney and bashed his head on a limestone boulder, it's unlikely he could have sustained two such wounds through an accidental fall, the researchers wrote in their paper, which was published today (May 27) in the journal PLOS ONE. In addition, the slow settling of the ground over hundreds of thousands of years didn't produce enough energy to cause the person's head wounds, Sala added.

That left one logical conclusion: murder.

"Based on the similarities in shape and size of both the wounds, we believe they are the result of repeated blows with the same object and inflicted by another individual, perhaps in a face-to-face encounter," Sala said. "We are not sure what the object was. However, possibilities include a wooden spear or a stone hand ax."

While ancient hominins may have cannibalized and butchered each other, there has been relatively little evidence for people using deadly force against other humans during the Paleolithic. At Shanidar Cave in Iraq, scientists have found a Neanderthal with a wound around his ribs, but that wound healed and was probably not lethal, the researchers wrote. In Sungir Cave in Russia, a skeleton bears a deadly spine fracture clearly caused by violence, but that could have been the result of a hunting accident, the researchers wrote.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus