Home Lighting Could Be Wireless Network

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Lights may soon do more than just shine in dark places – they might wirelessly connect your computer, phone or car to the Internet.

Sounds strange, but consider this. Remote controls already use infrared light to communicate with TVs and DVD players. Turning ceiling and reading lamps into wireless access points could allow you to get your Internet fix almost anywhere.

"We can provide ubiquitous communication if we have network access wherever there's lighting," said Thomas Little, a computer engineer at Boston University.

These aren't just any lights, though. Little and other researchers hope to piggyback on the spread of light-emitting diode (LED) light bulbs, which are finding favor as low-energy, long-lasting alternatives to the more conventional incandescent or fluorescent light bulbs.

Communicating with light

Using light to communicate is nothing new. The Romans used beacon fires to communicate between isolated forts, and lighthouses have long warned ships away from dangerous shores. Both NASA and the U.S. military have recently studied using lasers as a direct, high-speed form of communication.

However, the most common wireless network technologies today rely on radio frequencies. Those frequencies can get crowded and slow browsing speed to a crawl as more Internet users and devices occupy the same bandwidth.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"It's like being in a cocktail party," Little told LiveScience, noting that the "conversation gets louder and louder" as more people try to talk.

Light information bypasses the crowding problem by directly reaching individual users and devices, whether through a narrow laser or through light bulbs shining on a broad area. Information would first travel from a wireless router through a power line to a ceiling or lamp light. LED lights then transmit the data with flickering patterns undetectable by the human eye.

An added bonus for such a system is greater security, because light can't travel through walls like radio waves. A wireless network built on light would not go beyond the four walls of each room. Sneaky neighbors trying to catch free wireless Internet would have to crouch outside your window where light streams out.

A green wireless network

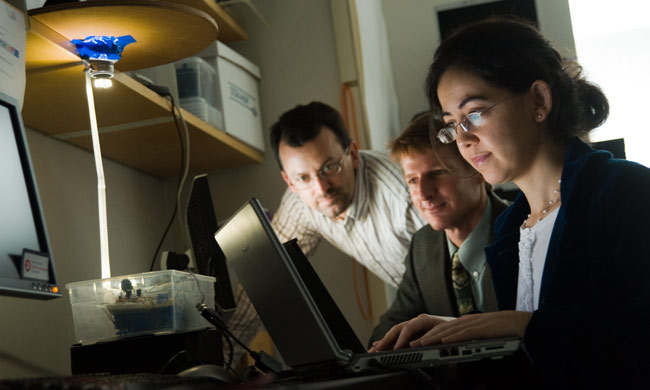

Little and his fellow researchers have already developed working prototypes using a modified wireless router and LEDs from a flashlight. The next big step in their plan relies on the rise of LED light bulbs in a world with ever-higher energy costs.

LEDs already appear in everything from computer screens to traffic lights, but have been slower to catch on as regular household lights because each bulb can cost $30 and up. Still, an LED bulb can last more than 50,000 hours compared with an incandescent bulb life of 1,000 hours – and the LED also cuts down on the electricity bill. So they are more costs effective.

"The real opportunity here is that LED has a lighting mechanism that offers such incredible energy savings over fluorescent bulbs," Little noted. He added that LED prices should come down over the next five to 10 years as more places use them.

Smart house, smart car

The effort is not limited to just enabling cheaper wireless networks across U.S. cities. Little talks about connecting everything wirelessly in a "smart" and energy-efficient home, including computers, TVs and thermostats.

Outdoor applications of local networks could also allow vehicles to communicate with each other. A car that senses a patch of ice through its anti-lock brakes might warn cars behind it automatically, with its LED brake lights transmitting the information.

"There's huge interest in the automotive and transportation industry," Little said. He pointed to a recent Audi demonstration of traffic lights communicating how soon they turn green, although he envisions using the actual light instead of a radio transmitter to tell cars.

Serious government dollars are backing such ideas. Little and 30 other researchers from Boston University, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute and the University of New Mexico received $18.5 million from the National Science Foundation for a five-year research grant to develop the technology.

Several global communications firms are also negotiating deals to use the technology, which means that applications could appear sooner than later.

"An aggressive partner could have something out on market within a year," Little said.

- Video – The Next Step in Alternative Fuel

- Top 10 Emerging Environmental Technologies

- Power of the Future: 10 Ways to Run the 21st Century

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus