Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

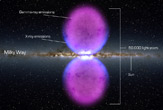

Scientists have detected two gigantic bubbles of high-energy radiation spilling out from the Milky Way's center that may have erupted from a supermassive black hole.

The mysterious structures each span 25,000 light-years across, meaning that together they cover more than half the area of the visible sky, and are emitting gamma rays, the highest-energy wavelength of light.

The bulbous features may be evidence of a burst of star formation a few million years ago, researchers said. Or they may have been produced when a supermassive black hole in the center of our galaxy gobbled up a bunch of gas and dust.

The newly discovered structures remain an enigma for now, scientists said. [New photo of gamma-ray bubbles]

"We don't fully understand their nature or origin," said study leader Doug Finkbeiner of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.

Scanning the gamma ray sky

Finkbeiner and his team used observations from NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope, which maps the sky's gamma-ray light. The scientists processed data from Fermi's Large Area Telescope, the highest-resolution gamma-ray detector ever launched.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

By filtering out the fog of background gamma rays suffusing the sky, the researchers were able to pick out the huge bubbles. The scientists weren't flying blind; previous studies by other astronomers using other instruments had found intriguing clues that a huge, previously unknown structure might be lurking near the Milky Way's heart.

X-ray observations from the German-led Roentgen satellite, for example, provided hints of bubble edges close to the galactic center. And NASA's Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe detected an excess of radio signals at the position of the gamma-ray bubbles, researchers said.

"We were definitely looking for something," Finkbeiner told reporters today (Nov. 9). "Some hints of this signal had been seen before, but not convincingly."

The two bubbles are dramatic, enigmatic and huge. They're emitting about the same amount of energy as 100,000 exploding stars, or supernovae, Finkbeiner said.

The bubbles' combined width of 50,000 light-years is about half of the entire Milky Way's diameter. The structures extend as far as the distance between our solar system and the galaxy's core (the bubbles don't envelop Earth; they spread out in a different plane).

A paper about the findings will be published in an upcoming issue of The Astrophysical Journal.

Possible causes

Researchers aren't yet sure what created the bubbles. But the structures appear to have sharp, well-defined edges, suggesting they were formed by a large, rapid and relatively recent release of energy.

Two leading candidate causes, according to Finkbeiner, are a surge of star formation several million years ago and a burst of activity by the Milky Way's central black hole, which is as massive as four million suns.

Astronomers have observed powerful jets blasting from the supermassive black holes in other galaxies. These jets are fueled by matter falling into the black hole.

"These monsters, once fed, can produce very powerful explosions," said David Spergel, chair of Princeton University's astrophysics department.

While there is no evidence the Milky Way's black hole has such jets today, it may have in the past, researchers said.

"This might be the first evidence for an outburst of activity of the black hole at the center of the galaxy," Finkbeiner said.

Scientists are now conducting more analyses to get a better handle on just what drives the newly discovered bubbles, and what they can reveal about the nature of the Milky Way and the universe.

"Whatever the energy source behind these huge bubbles may be, it is connected to many deep questions in astrophysics," Spergel said.

- Video: Giant Gamma-ray Bubbles Found Around Milky Way

- The Strangest Things in Space

- Top 10 Star Mysteries

This article was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site of LiveScience.com.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus