Neanderthal 'Family' Possibly Victim of Cannibal Attack

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

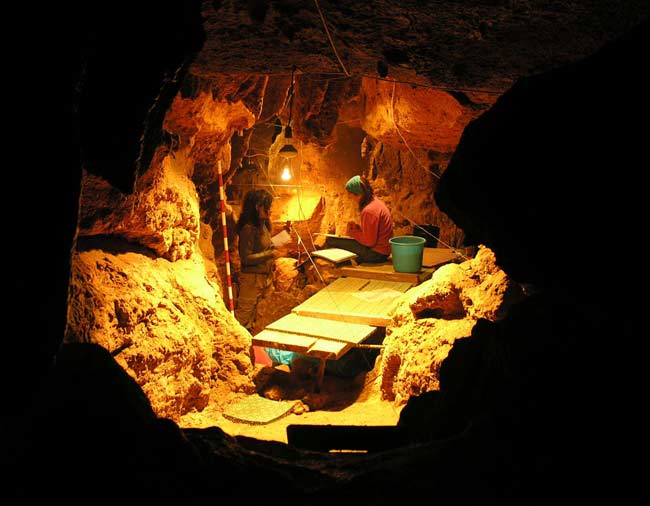

The remains of a possible family group of Neanderthals, including an infant, were discovered in a cave in Spain, researchers reported. The bones of the 12 individuals show signs of cannibalism, suggesting another Neanderthal group came along and chowed down on the meat.

This group of Neanderthals died some 49,000 years ago, the research suggests. Shortly after, a violent storm or other natural disaster likely caused the cave to collapse and bury their remains at the El Sidron site.

The finding, detailed last week in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, reveals for the first time genetic evidence of a social kin Neanderthal group. Analyses suggest the group included three adult males, three adult females, three adolescents (possibly all male), two juveniles (one 5 to 6 years old and the other from 8 to 9), and an infant. [The Many Mysteries of Neanderthals]

"I think this is a pretty significant piece of research, and [it] really adds to the forensic understanding of what happened in that cave," said John Hawks, an anthropologist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, who was not involved in the current study, referring to the possibility of cannibalism.

"I don't see any real reason to question the scenario, but like most cases of archaeological finds there are always questions as to the fidelity of the evidence," Hawks told LiveScience in an e-mail. "That being said, my inclination would be to revisit some other Neanderthal sites keeping in mind the relatively strong evidence of cannibalism and systematic 'warfare' at El Sidron. I think there are other pieces that can be put together into a stronger case across many sites — that is I don't think this was a single incident without parallels elsewhere"

Neanderthal family

The remains have been unearthed over the last 10 years. "They were difficult to isolate because they are highly fragmented, due to the cannibalism," said lead author Carles Lalueza-Fox, of the Institute of Evolutionary Biology in Barcelona, adding, they included: lots of teeth, mandibles, long bones and skull fragments.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers used mitochondrial DNA, which resides in the energy-making structures of cells, to determine who was related to whom. This type of DNA, unlike nuclear DNA, gets passed down from females only. To figure out sex of the individuals, the team analyzed the remains for a Y chromosome, since only males are equipped with a Y.

Results suggested the child about 8 to 9 years old was the offspring of one of the female adults, while another adult female was the mother of the infant and child about 5 or 6. The three adult males shared mtDNA, suggesting they were brothers or otherwise related through the maternal line.

Past research of the nuclear DNA from remains of the women who bore the 5- or 6-year-old child suggests she was a redhead, Lalueza-Fox said during a telephone interview. Those results were published in a past issue of the journal Science.

Clues to cannibalism

"There are many different markings in many different bones in all 12 individuals, including traditional cut marks to disarticulate bones and remove muscle insertions, snapping and fracturing of long bones to extract the marrow," Lalueza-Fox told LiveScience.

These marks "could indicate that the assemblage corresponds to a Neandertal group processed by other Neandertals on the surface," the researchers wrote. (Neandertal is an alternative spelling of Neanderthal.)

He pointed out that cannibalism is not rare among Neanderthals, though the current finding is unique in its scale (12 individuals). "The dating of 49,000 years ago, on the other hand, indicates that the cannibals should be other Neandertals, since modern humans were not around at that time in Europe," he said.

That means the men in the group are kin, while the women came from different kin groups — a phenomenon called patrilocality. "The authors' hypothesis about patrilocality is consistent with the mtDNA, and I think it is likely to be the correct one," Hawks writes in his blog. He adds, however, that the interpretation isn't foolproof.

"For one thing, Neandertals are already known to be relatively low in mtDNA variation, with very little regional population structure in the mtDNA. In such a population, it wouldn't be surprising to find individuals sharing the same mtDNA haplotype, even if they were not close kin," Hawks writes.

- Weird Ways We Deal With the Dead

- Gnawed Bones Reveal Cannibal Cavemen

- Top 10 Things That Make Humans Special

You can follow LiveScience Managing Editor Jeanna Bryner on Twitter @jeannabryner.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus