Rare Fossil Octopuses Found

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

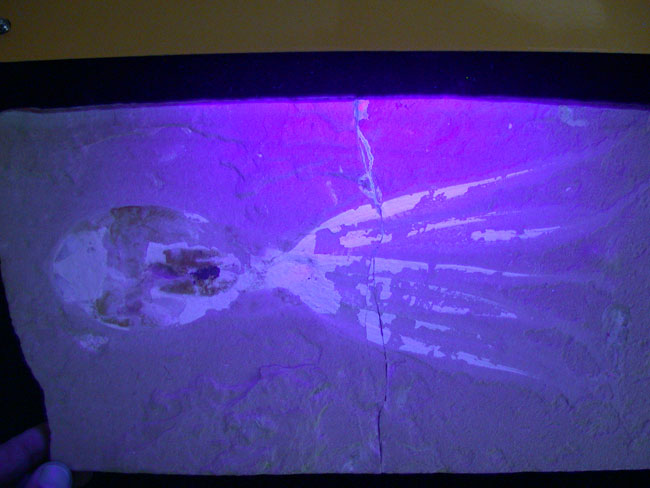

It's hard enough to find fossils of hard things like dinosaur bones. Now scientists have found evidence of 95 million-year-old octopuses, among the rarest and unlikeliest of fossils, complete with ink and suckers.

The body of an octopus is composed almost entirely of muscle and skin. When an octopus dies, it quickly decays and liquefies into a slimy blob. After just a few days there will be nothing left at all. And that assumes that the fresh carcass is not consumed almost immediately by scavengers.

The result is that preservation of an octopus as a fossil is about as unlikely as finding a fossil sneeze, and none of the 200 to 300 species of octopus known today had ever been found in fossilized form, said Dirk Fuchs of the Freie University Berlin, lead author of the report.

Fuchs and his colleagues now have identified three new species of octopuses (Styletoctopus annae, Keuppia hyperbolaris and Keuppia levante) based on five specimens discovered in Cretaceous Period rocks in Lebanon. The specimens, described in the January 2009 issue of the journal Palaeontology, preserve the octopuses' eight arms with traces of muscles and rows of suckers. Even traces of the ink and internal gills are present in some specimens.

"The luck was that the corpse landed untouched on the sea floor," Fuchs told LiveScience. "The sea floor was free of oxygen and therefore free of scavengers. Both the anoxy [absence of oxygen] and a rapid sedimentation rate prevented decay."

Prior to this discovery only a single fossil species was known, and from fewer specimens than octopuses have legs, Fuchs said.

What most surprised Fuchs and his colleagues Giacomo Bracchi and Robert Weis was how similar the specimens are to modern octopus. "These things are 95 million years old, yet one of the fossils is almost indistinguishable from living species," Fuchs said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This provides important evolutionary information, revealing much earlier origins of modern octopuses and their characteristic eight-legged body-plan, Fuchs said.

Unlike vertebrate animals, octopuses lack a well-developed skeleton, which allows them to squeeze into spaces that a more robust animal could not.

"The more primitive relatives of octopuses had fleshy fins along their bodies. The new fossils are so well preserved that they show, like living octopus, that they didn't have these structures," Fuchs said.

This insight pushes back the origins of the modern octopus by tens of millions of years, he said.

- Video: A Surprising Fish Tale

- Gallery: Small Sea Monsters

- Gallery: Under the Sea

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus