Gunk in T. Rex Fossil Confirms Dino-Bird Lineage

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

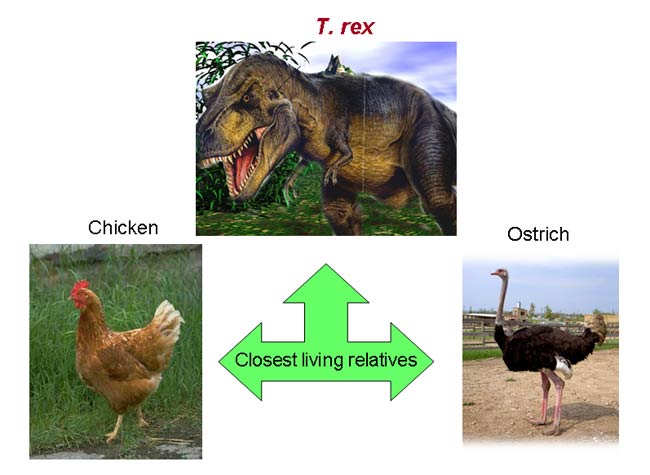

Tyrannosaurus rex just got a firm grip on the animal kingdom's family tree, right next to chickens and ostriches. New analyses of soft tissue from a T.rex leg bone re-confirm that birds are dinosaurs' closest living relatives.

"We determined that T. rex, in fact, grouped with birds – ostrich and chicken – better than any other organism that we studied," said researcher John Asara of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School. "We also show that it groups better with birds than [with] modern reptiles, such as alligators and green anole lizards."

Scientists long suspected non-avian dinosaurs were most closely related to modern-day birds. This idea initially rested largely on similarities between the outward appearances of bird and dinosaur skeletons. Later, further evidence on the close evolutionary relationships among birds and non-avian dinosaurs accumulated.

A leg bone full of key gunk

The latest evidence comes from an ancient femur bone unearthed in 2003 by Jack Horner of the Museum of the Rockies in the Hell Creek Formation, a fossil-packed area that spans Montana, Wyoming and North and South Dakota.

It seems some 68 million years ago, a teenage T. rex died and left behind a drumstick-shaped femur bone that today still contains intact soft tissue and the oldest preserved proteins discovered to date.

Though no genetic material was preserved, researchers were able to extract the proteins from the collagen tissues.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The proteins are what carry out the function inside the cells and organs. So the protein does a lot of the work. That [protein] sequence was derived from DNA," Asara told LiveScience. In the case of T. rex's collagen, "it was responsible for making hard bone so that the dinosaur could stand."

By comparing the dino's protein sequences with those of 21 living organisms, a team of researchers say they have locked in the dinosaur-bird link.

Mastodons and K-T boundary addressed

The study, detailed in the April 25 issue of the journal Science, also shored up the evolutionary link between the extinct mastodon and the modern-day elephant.

A slew of advanced techniques — such as the protein sequencing — are shedding more light on the lives and deaths of now-extinct animals such as mastodons and dinosaurs. For instance, another study published this week in Science pinned down more accurately the point in geologic time when dinosaurs, pterosaurs, plesiosaurs, mosasaurs and many plant and invertebrate animal species went extinct (as a result of what is called the K-T extinction event).

The new figure for that event is 65.95 million years ago, a few hundred thousand years later than previous estimates, says lead author Klaudia Kuiper of Utrecht University in the Netherlands.

The massive extinction event was likely the result of a meteor impact and/or volcanic activity on Earth that reduced sunlight and made photosynthesis very difficult for plants.

Reptiles, alligators, ostrich added

The current family-tree research builds on protein analyses of the T. rex bone by Asara and his colleagues, published last year in the journal Science.

"Now it's gone a lot further," Asara said. "We had no reptiles represented last year. We now have alligator and ostrich represented." The researchers also refined the family relationships using more sophisticated algorithms.

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Paul F. Glenn Foundation and the David and Lucile Packard Foundation.

- Avian Ancestors: Dinosaurs That Learned to Fly

- A Brief History of Dinosaurs

- Image Gallery: Dinosaur Art

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus