Huge Ocean Blooms Don’t Wait for Spring, Study Finds

Microscopic, plant-like ocean creatures called phytoplankton spend their winters bulking up for the giant blooms that can cover thousands of square miles of the ocean surface come spring, a new study suggests.

The findings challenge the conventional wisdom that phytoplankton growth in the temperate oceans is spurred by the heating of the surface of the ocean and the increased light during the spring, which would provide extra fuel for the growing creatures. This 50-year-old theory is outdated, said study researcher Michael Behrenfeld, a botanist at Oregon State University in Corvallis.

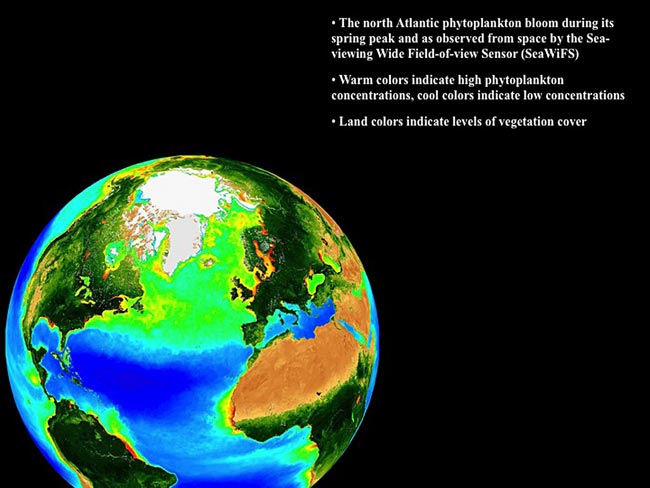

"The old theory made common sense and seemed to explain what people were seeing," Behrenfeld said. "It was based on the best science and data that were available at the time, most of which was obtained during the calmer seasons of late spring and early summer. But now we have satellite remote sensing technology that provides us with a much more comprehensive view of the oceans on literally a daily basis."

Those data, he said, "strongly contradict" the old theory.

The data reveal that spring phytoplankton blooms begin much earlier than previously thought, in the fall and winter. As winter storms become more frequent and intense, the ocean's biologically rich surface layer mixes with cold water from the deep sea. This dilutes the concentration of both the phytoplankton and the very tiny marine animals, zooplankton, that feast on it — making it more difficult for the zooplankton to find and eat it. More phytoplankton survives, and its growth skyrockets during the dark, cold days of winter.

Not accounting for how the activity of the zooplankton changes with the seasons, in particular their feeding rate on the phytoplankton, was the old theory's fundamental flaw, Behrenfeld said.

"To understand phytoplankton abundance, we've been paying way too much attention to phytoplankton growth and way too little attention to loss rates, particularly consumption by zooplankton," Behrenfeld said. "When zooplankton are abundant and can find food, they eat phytoplankton almost as fast as it grows."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The new theory about phytoplankton blooms is based on a nine-year analysis of satellite records that shows the phytoplankton growth surge during the middle of winter.

"What the satellite data appear to be telling us is that the physical mixing of water has as much or more to do with the success of the bloom as does the rate of phytoplankton photosynthesis," Behrenfeld said. "Big blooms appear to require deeper wintertime mixing."

Phytoplankton is the ultimate basis of the ocean food chain, and some regions with large seasonal phytoplankton blooms are among the world's most dynamic fisheries. The new theory of phytoplankton growth raises concerns that global warming, may actually curtail ocean productivity in some places rather than stimulating it, Behrenfeld said.

The study is detailed in the April edition of the journal Ecology.

This story was provided by OurAmazingPlanet, a sister site to Live Science.