Arsenic Bacteria Controversy Gets a Postmortem

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

SAN FRANCISCO – Take a simmering broth of fast-swirling news on the blogosphere and Twitter, stir in some arsenic bacteria and add a pinch of "extraterrestrial." The media explosion that followed has led both scientists and journalists to reconsider how they should tell the world about possibly groundbreaking science without creating an utter mess.

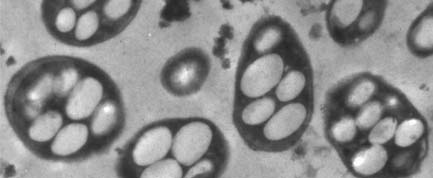

The loud controversy regarding the exact nature of the microbe known as GFAJ-1 became the focus of a panel here at the 2010 fall meeting of the American Geophysical Union on Thursday (Dec. 16). Despite ongoing debate about how exactly the microbe incorporates arsenic into its DNA – the microbe's claim to fame – one of the researchers behind the discovery made very clear that it does not represent a new life form.

"It's not a new form of life," said Ron Oremland, a scientist with the U.S. Geological Survey in Menlo Park, Calif. "It's actually a member of a well-defined genus that grows in salt water, called Halomonas."

The panel traced the uproar back to a NASA press release that came out before the main study was unveiled. The release suggested that the new research would "impact the search for evidence of extraterrestrial life" – words that set off breathless online speculation about a microbe that supposedly had a wildly different evolutionary origin than the rest of life on Earth.

"First in my view – and I'm certainly not being original about this – NASA's announcement of the press briefing was ill-advised and clearly fed the online rumor mill," said Robert Irion, director of the science communication program at the University of California at Santa Cruz.

The U.S. space agency actually organized the panel to dissect the fallout from the arsenic bacteria announcement. But no NASA representative sat on the panel, and so there was no response to any of the panel's criticisms regarding NASA's role in stoking online speculation.

Nobody said it was easy

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Oremland and his colleagues who published the controversial paper in the journal Science based the discovery upon decades of work with microbes. During the panel, Oremland described his past studies of other bacteria that could "breathe" arsenic in combination with using sunlight to get needed energy. [Q&A: 'Science' Journal Official Talks Arsenic-Based Life]

He eventually met microbiologist Felisa Wolfe-Simon at a conference. She suggested that bacteria might not only use toxic arsenic to breathe, but might also use it to substitute for the phosphate molecules that are part of the DNA double helix structure.

That sounded crazy to Oremland. But eventually he reconsidered.

"We have nothing to lose," Oremland recalled."This is such an easy experiment to set up, it's simple."

To the researchers' amazement, they found the GFAJ-1 microbe from Mono Lake, Calif., taking up arsenic into its DNA backbone – at least when the preferred phosphate was unavailable. That did not change the actual DNA base pairs that form the microbe's genetic code, but it still seemed like a remarkable adaptation by a resilient little life form.

The group did additional tests to "elevate the level of proof," and then submitted a paper to Science with Wolfe-Simon as lead author. Their work passed the peer review by Science's anonymous expert reviewers.

Fast and furious

Both NASA and the journal Science prepared press releases and material for reporters while the study was still held under wraps (embargoed) before public release. Then the online rumors began flying with a vengeance.

The U.S. space agency's press release was a "misleading teaser" that had been all-too-easily sensationalized, Irion said.

Irion also saved some criticism for the journal Science's press materials, which had described the bacteria as being able to "live and grow entirely off arsenic." The same material added that "Arsenic had completely replaced phosphate in the molecules of bacteria right down to its DNA," without clarifying that arsenic only replaced part of the double helix's backbone structure.

Irion also pointed out how the journal Science pre-released a story written by its independent news branch. That story included a more balanced view of the finding and quoted serious reservations by one skeptical scientist who also ended up as part of NASA's press conference.

Scientists under the microscope

As a result of the teasers, the early media coverage positively glowed with erroneous exuberance. The tech blog Gizmodo declared: "Hours before their special news conference today, the cat is out of the bag: NASA has discovered a completely new life form that doesn't share the biological building blocks of anything currently living in planet Earth. This changes everything."

But scientists who finally read the paper took a much more sober and skeptical view of the finding. Rosie Redfield, a microbiologist at the University of British Columbia in Canada, detailed her concerns about the paper's methods and possible contamination of the results in her blog. Then she used Twitter to summarize her take as, "Bottom line: it's shamefully bad science."

Her remarks have become the most public example of the scientific criticism aimed at the arsenic bacteria paper. Yet such harsh critiques are not out of the ordinary for provocative new studies, said Charles Petit, lead writer of the media-watch organization Knight Science Journalism Tracker in Berkeley, Calif.

Scientific criticism with such a rough tone is not new – plenty comes up in e-mails and in the halls of conferences all the time, Petit pointed out during the panel. The difference here was that social media tools had allowed much of that private conversation among scientists to become public.

Responding to criticism

The authors of the arsenic bacteria paper quickly found themselves buried by messages, and in some cases seemed uncertain about how to respond to the public criticisms.

"I have no idea what to do with the blogosphere," Oremland confessed during the panel."I apologize for any errors I made, but I felt that with no guidelines I couldn't respond."

That confusion may rest upon the unusually public airing of the critiques, as opposed to dealing with formal letters or counter-studies submitted through science journals. On the Internet, both researchers and members of the public alike can directly contact the authors of new papers.

"What is peer review these days? What is your peer in the information age?" said Andrew Steele, a scientist at the Carnegie Institute in Washington D.C., during his participation in the panel by phone."It's very difficult to mediate."

Either way, journalists had complained of the study authors being unresponsive to criticism from outside experts that they consulted for their stories. Ginger Pinholster, director of the office of public programs at the American Association for the Advancement of Science, or AAAS (publisher of the journal Science), had previously told LiveScience: "We encourage all Science authors to respond promptly to media queries."

Wolfe-Simon, the lead author on the arsenic bacteria paper, followed the panel's webcast and live-tweeted her responses in real-time.

"We, the entire team, were happy to engage. It was the sheer volume of requests coming in!" she wrote under her Twitter handle.

Brave new world

No members of the panel had immediate answers about how to reconcile the slower pace of scientific validation and confirmation with the "blindingly fast" world of online news that can turn any latest scientific development into a flashpoint.

Petit described information in general as "good," but also "messy." He added that having more information strengthened society and would lead to more info-savvy citizens – even in the case of the controversial WikiLeaks.

"I think this is a good thing, but it is painful," Petit said. "I wouldn't know what you should do either, when you're faced with a blizzard of criticism from lunatics to respected colleagues, and it's all coming in sort of unfiltered."

The difference between clear conclusions and subtle inferences drawn from research is often lost in the frenzied pace of new media, Irion noted. His advice was that "qualifiers are your friends," and he suggested deploying them frequently and up front in press releases.

Moving forward

A grand, messy discussion continues to evolve. On Thursday (Dec. 16), Wolfe-Simon and her colleagues posted the first short version of their answers to frequently asked questions from their critics – and it has already drawn a response from Redfield on her blog.

Oremland reminded the panel audience that he, Wolfe-Simon and the rest of the team would make their microbe cultures available to researchers so that they could try to duplicate their experimental results.

"If it's a fluke – and I'm first to admit it might have been a fluke, but we thought we were pretty tight on this – then we stand to suffer," Oremland said."That's the way it should work."

The GFAJ-1 microbes at the heart of the controversy have been unable to comment thus far. But an anonymous wit used the Twitter handle @arsenicmicrobes to send the following tweet shortly after the first news broke: "We come in peace."

- Extremophiles: World's Weirdest Life

- Kerfuffle! Scientific Discoveries Cause a Ruckus

- Strangest Places Where Life Is Found on Earth

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Jeremy Hsu on Twitter @ScienceHsu.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus