Mystery of Half-Male Chickens Solved

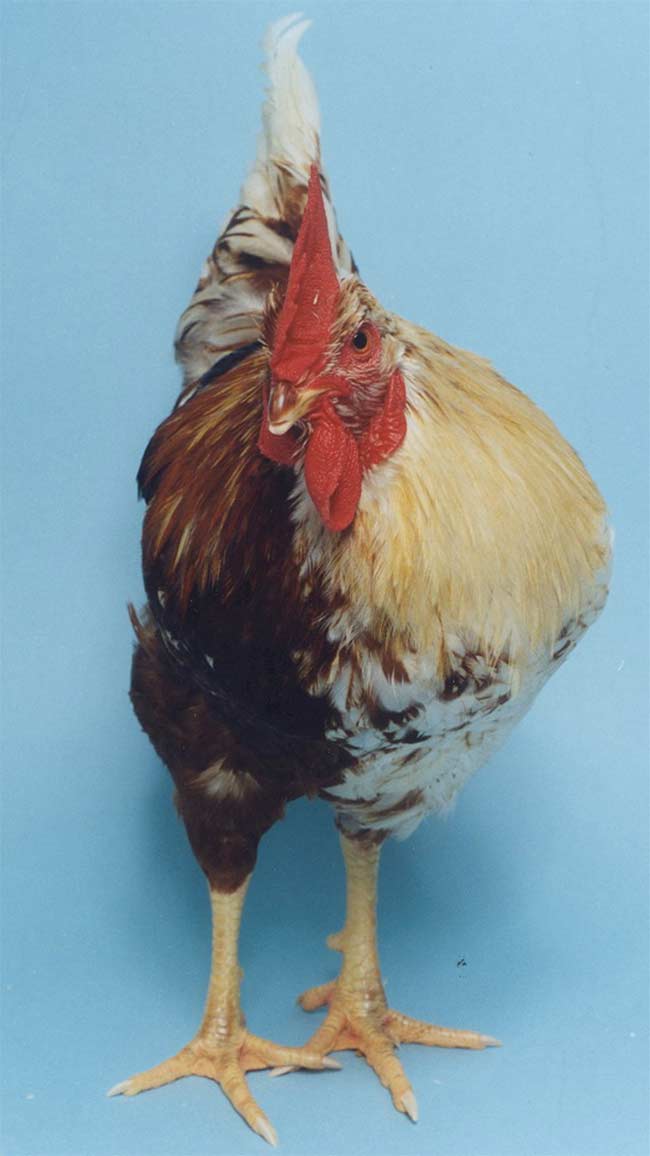

Some chickens have sexual-identity issues, waddling around with half-male and half-female plumage.

Now researchers have figured out the cause of the gender-confusing traits: Half of their bodies are full of female sex cells, while the other half contains mostly male cells.

"This research has completely overturned what we previously thought about how sexual characteristics were determined in birds," said study researcher Michael Clinton of the University of Edinburgh, Roslin, in Scotland. "We now believe that the major factors determining sexual development are built into male and female cells and derive from basic differences in how sex chromosome genes are expressed."

The findings are detailed this week in the journal Nature.

Previously, scientists thought whether an animal became male or female occurred during embryo development when genetic and other factors instructed gonads to become ovaries or testes. These organs, in turn, released hormones that signaled to the brain and reproductive tract, "You are female (or male)." In chickens, those same hormones were also thought to signal gender to tissues that would become feathers and muscles.

The new research, however, suggests "in birds, sex determination occurs in cells across the entire body, not just in the gonads," Lindsey Barske and Blanche Capel of Duke University Medical Center write in an accompanying perspective article in the same issue of Nature.

In addition to plumage color, the male and female cells also are involved in wattle length (fleshy growth hanging from the head or neck) and comb height.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Sexual identity

In most mammals, including humans, females have two X (sex) chromosomes, while males have one X and one Y. For birds, the sex chromosomes are labeled as Z or W and females have dissimilar chromosomes (ZW), while males have matching ones (ZZ).

The researchers examined three of these funky chickens, testing the sex chromosomes from various tissues throughout the chickens' bodies. Tissues from the "male" side of the body had mostly ZZ cells (about 80 percent), while those on the "female" half had higher proportions of ZW cells.

Since all the tissues in the body are exposed to the same hormones, the researchers suspected the cells must just respond differently to the hormones. In other words, the body's cells are set in their sexual identity no matter whether they get a squirt of female or male hormones.

"So that made us think the cells must have a sex identity," Clinton said.

The research team included University of Edinburgh scientists Debiao Zhao and Derek McBride.

Female and male cells

To test this idea, they transplanted female chicken cells into a developing male embryo and male cells into a developing female embryo. They did this by inserting the cells into a tiny hole in the eggshell, sealing it up and waiting a week before analyzing the tissues of the developing chicken embryos.

Results showed that ZW donor cells (female) "knew" they were gonads but they didn't get incorporated into the testes, and ZZ donor cells (male) didn't get incorporated into the ovaries and also didn't express the female hormone called aromatase in the host's ovary.

That suggests "their sexual identity was already fixed by the time they arrived in the host tissue," Barske and Capel write.

As for why chickens evolved this system in which sexual appearance is controlled primarily by the sexual identity of cells rather than hormones, Clinton speculates that it's just a simpler system compared with the hormonal one that mammals use.

"We think all birds will be like this, and it's possible other vertebrates will have elements of this system," Clinton told LiveScience.

- Top 10 Amazing Animal Abilities

- World's Strangest Creature: Part Mammal, Part Reptile

- Animal Sex: No Stinking Rules

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus