Load of Croc: 'Bird' Teeth May Actually Be from Teenage Crocodilians

For nearly 50 years, researchers have found mysterious, disembodied teeth dating to the dinosaur age in southern Alberta, Canada. The teeth lacked jawbones, so researchers weren't sure what animals these teeth came from, although many suspected the pointy chompers belonged to ancient birds.

Now, new research is turning that idea on its head: These cryptic teeth aren't avian in nature, but likely those of juvenile crocodilians, said Sydney Mohr, a master's student in biological sciences at the University of Alberta, who is studying the teeth.

"They've basically always been referred to as bird teeth," Mohr said, "but with not much evidence to back that up." [Images: How the Bird Beak Evolved]

The roughly 100 teeth in question date to the Late Cretaceous, from about 75 million to 65 million years ago, when many birds still had teeth, unlike modern birds, Mohr said. During that time, Alberta was warmer than it is today, and although the environment varied from wet to dry over the ages, the region was largely covered with wetlands and forests during that time, she said.

Curiously, it's extremely rare to find ancient bird remains in southern Alberta, she said. Granted, finding fossilized birds is challenging in most places, because birds have delicate skeletons that are easily crushed. But Mohr thought it was strange that bird remains were "almost never" discovered in the area, except for these mysterious teeth, she said.

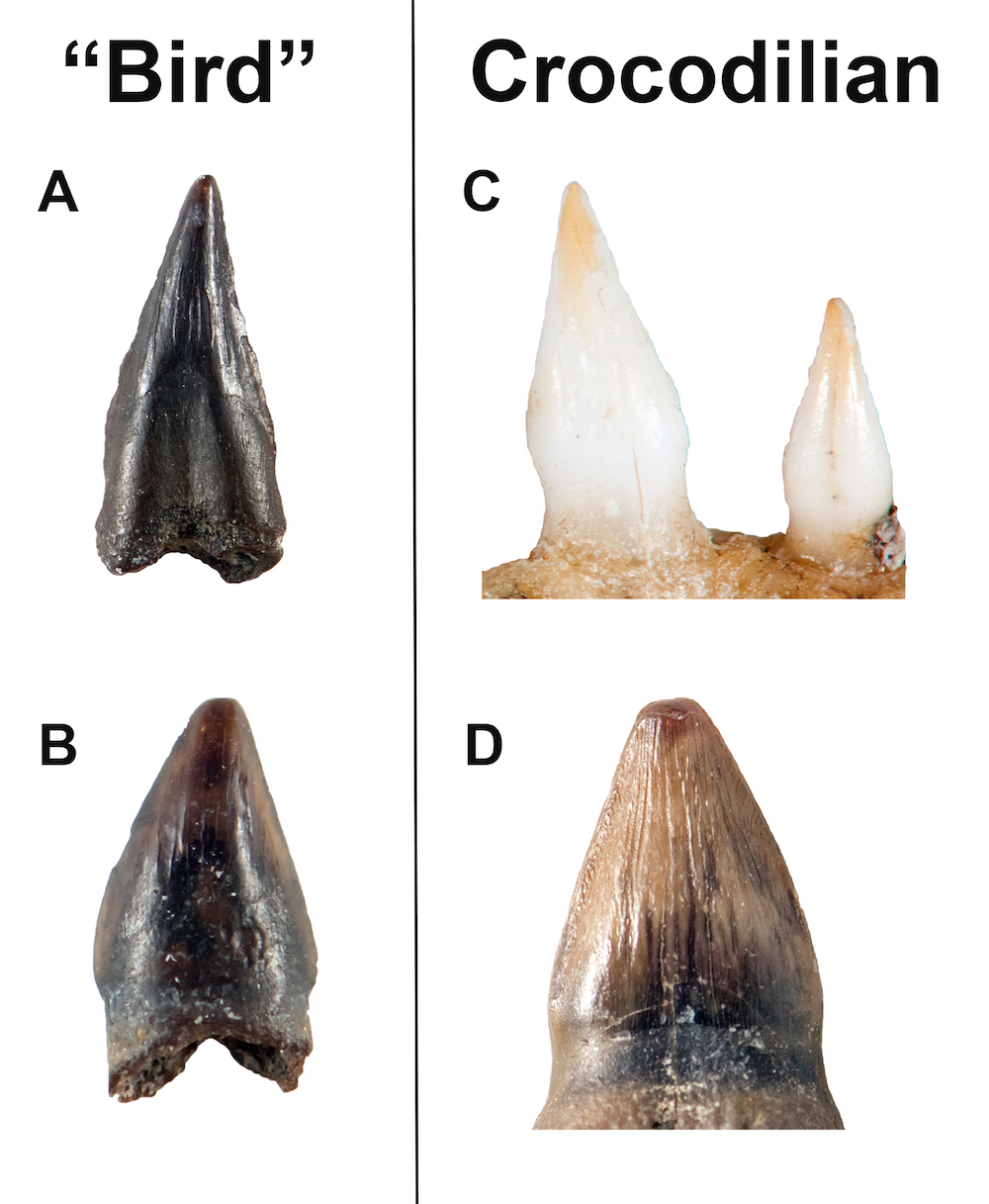

To learn more, Mohr analyzed the teeth. "No one has ever taken a really good look at them," she said. She compared them to the teeth of contemporary nonavian dinosaurs: the ancient birds Hesperornis and Ichthyornis; a small, extinct reptile in the genus Champsosaurus; and crocodilians, a group that includes crocodiles and their relatives.

A thorough examination revealed that the teeth were similar in size, shape and surface ornamentation to the teeth of juvenile crocodilians, Mohr said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Rocky road

But these findings aren't definitive, Mohr said. Without a fossilized skeleton, it's hard to say what animal sported these teeth. For instance, while the teeth are approximately the same size as those of a juvenile croc, it's possible the teeth belonged to a small, adult crocodilian that had tiny teeth, Mohr said. The teeth could also belong to a theropod, a group of bipedal, mostly meat-eating dinosaurs such as Velociraptor, Mohr added.

It's also possible that some of the teeth did, in fact, come from birds, Mohr said. But even if they didn't, that doesn't mean prehistoric birds didn't fly over southern Alberta. It's possible that toothless birds lived there, or that toothed-bird remains simply weren't preserved, she said.

Although Mohr can't conclusively name the teeth's owner, the finding is important, she said. Other researchers have used these mysterious teeth to assess avian diversity in in the Late Cretaceous period of North America. "So, if they're not birds, we have a problem," Mohr said.

Perhaps the teeth have different characteristics from one another because crocodilians have teeth that are different in the front, middle and back of their mouths, she said. "It's possible that these teeth are actually a better measure of variation within a single jaw rather than species variation," Mohr said. [Image Gallery: 25 Amazing Ancient Beasts]

Other studies have analyzed the teeth under the assumption that they belonged to birds, and thus ascribed each tooth's features to that of an ancient avian — so if these are not actually bird teeth, it would be a setback, she added.

As such, Mohr urged researchers to be cautious of material that is ambiguously classified. "We have to be careful about diagnosing isolated and fragmentary material and using it in analyses without knowing exactly what it is," she said.

The research, which has yet to be published in a peer-reviewed journal, was presented Aug. 23 at the 2017 Society of Vertebrate Paleontology meeting in Calgary, Canada.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.