Ancient Water Bird Survived Attack by Short-Necked 'Sea Monster'

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

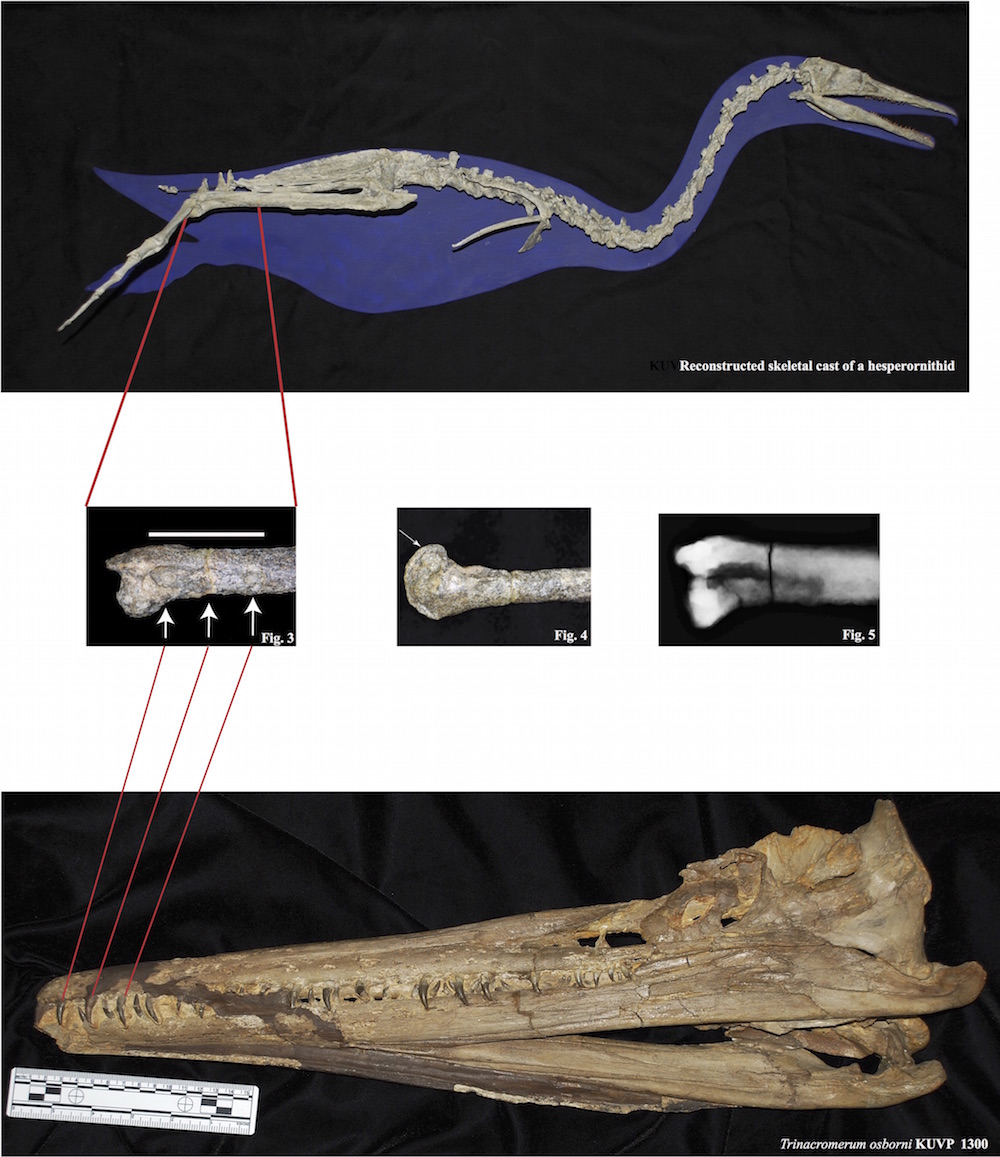

Scientists have found what may be the world's luckiest Hesperornis — an ancient water bird that escaped the snapping jaws of a plesiosaur about 70 million years ago in prehistoric South Dakota.

Still, the plesiosaur got a good bite out of the Hesperornis, a large, flightless diving bird that lived during the late Cretaceous period, when dinosaurs roamed the world.

"Basically, the plesiosaur came in from the side," said study co-author Bruce Rothschild, a professor of medicine at Northeast Ohio Medical University. "That probably was what allowed the bird to escape, because when [the plesiosaur] got the initial grip, and released to get a better grip, the bird got away." [Beastly Feasts: Amazing Photos of Animals and Their Prey]

Researchers came across the Hesperornis specimen while sifting through the Princeton University Collection of fossils at the Yale Peabody Museum. The roughly 3-feet-long (1 meter) skeleton had a damaged left tibiotarsus, or leg bone, that, upon closer inspection, looked like it had tooth marks on it.

The researchers put on their detective hats, and set out to determine what had bitten the bird. The suspects were a mosasaur (a large reptilian predator that swam in Earth's prehistoric oceans), a Xiphactinus (a giant prehistoric carnivorous fish) and a plesiosaur (another type of carnivorous marine reptile), Rothschild said.

He and his colleagues went to the University of Kansas, which has the largest collection of mosasaur fossils in the world (largely because an ancient seaway swimming with ancient reptiles once covered middle America, he said). They looked at skulls from the mosasaur Clidastes, the plesiosaurs Dolichorhynchops osborni and Trinacromerum bentonianum, and Xiphactinus.

The best piece of evidence was the spacing of the teeth marks. The fossil showed that whatever bit the bird had evenly spaced teeth, which didn't match the irregularly spaced teeth of the mosasaur or the tooth patterns of the Xiphactinus.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We basically did the Cinderella routine, to see whose teeth fit the 'slipper,'" Rothschild told Live Science.

The plesiosaur's teeth were a perfect fit. It's unclear what species of plesiosaur did the deed, but it's likely that a small, short-necked plesiosaur with a long, narrow snout and equally spaced teeth chomped down on the Hesperornis' leg, he said.

The bird's leg shows signs of healing, but the injury appears to have altered its subsequent growth. The bird was a juvenile when it was attacked, and it later developed osteoarthritis, probably because the bite caused its bones to permanently rub against one another, Rothschild said.

"Osteoarthritis had not been recognized previously in any kind of marine animal," he said. It's also the first evidence that plesiosaurs, which typically ate fish, also fed on birds, he said.

The finding is a reminder that fossils can tell wild tales about animals that lived along ago.

"Fossils are not static bits of information, but actually tell you about the behavior of the animal," Rothschild said. "It shows the resilience of the bird to survive the injury."

The study will be published in the August 2016 issue of the journal Cretaceous Research.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus