How the Net Neutrality Debate Affects Your Internet

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

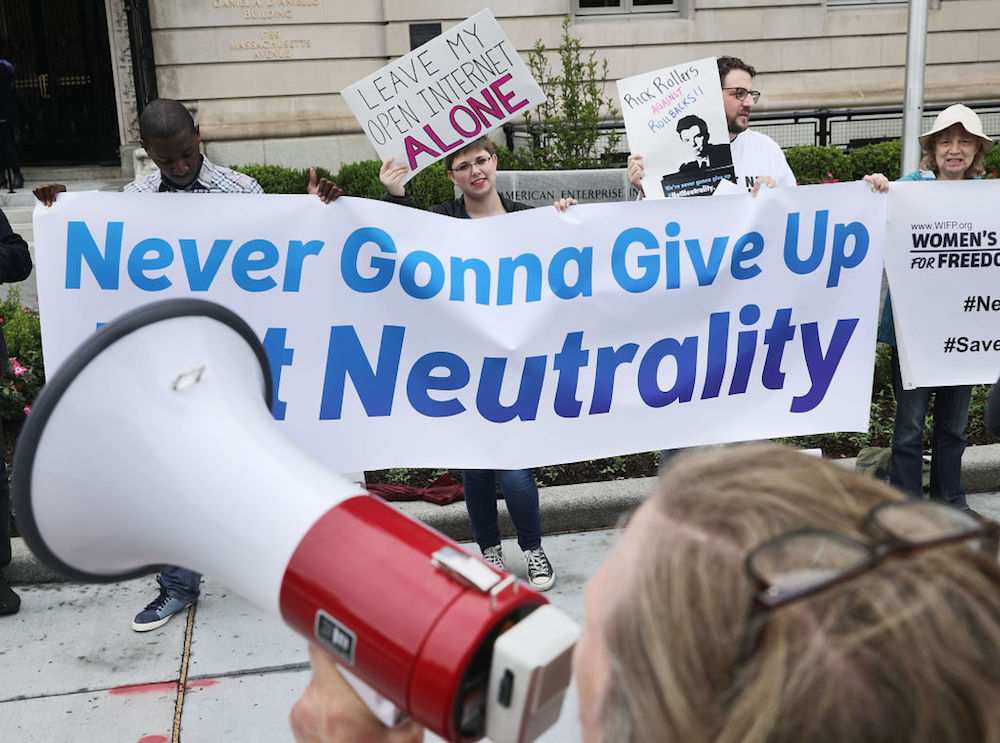

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) voted last week to start dismantling 2015 rules that regulated internet service providers the same way as utilities. So what does that mean for your internet access?

The answer to that question will take months to hash out.

The debate swirls around two related issues: whether the internet is a public utility, and how (or if) to ensure a concept known as net neutrality. Net neutrality is the framework for an internet in which all data is treated equally. For example, a provider such as Comcast can't throttle back Netflix's streaming speeds because Netflix's video content competes with its cable offerings. Nor can a company block legal websites or apps, or require them to pay extra for a broadband boost. [6 Politicians Who Got the Science Wrong]

Net neutrality advocates argue that the regulations on internet service providers (ISPs) enacted under President Barack Obama's administration are necessary to ensure that providers don't try any of these strategies. Meanwhile, advocates of Thursday's FCC decision — including FCC Director Ajit Pai — argue that market forces and alternative rules could keep the internet neutral, and that the current FCC regulations stifle innovation.

Here's how we got here.

How do you regulate the internet?

The net-neutrality debate is perhaps the biggest internet argument of all, and it's been going on since the late 1990s. In 1996, Congress passed the Telecom Act, leading the FCC to classify cable broadband providers as "information services" rather than "telecommunications services," which would have been subject to stricter regulation.

The FCC did, however, want to do some regulating. In 2010, it passed the Open Internet Order, which prohibited ISPs from blocking, throttling or offering paid prioritization. Blocking is cutting off access to legal websites, devices or apps; throttling is degrading the service to certain devices, websites or apps so as to render them unusable; and paid prioritization is offering sites, apps or device-makers the opportunity to pay for a speed boost for their traffic.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Net-neutrality advocates argue that without these rules, large, established companies will dominate the web, while startups without the cash to pay for access will struggle. Without regulation, ISPs could also block content from a particular political position or point of view, stymying free speech.

Unfortunately for the FCC, Comcast challenged the rules over whether the provider could slow down traffic through BitTorrent, peer-to-peer sharing software used to transfer large files like movies or audio clips.

In 2010, a federal appeals court ruled in that case that the FCC didn't have the authority to regulate ISPs such as Comcast. The FCC formalized the order as rules, but that workaround didn’t fly in court either: In 2014, a lawsuit by Verizon also ended with the court ruling that the agency had overstepped its boundaries by trying to regulate ISPs as if they were old-fashioned phone companies, or "common carriers."

That ruling set the stage for the last net-neutrality fight in 2015. At the time, the Obama White House came out strongly advocating for reclassifying ISPs as common carriers — essentially, as utilities. The FCC under then-Chairman Tom Wheeler ended up taking this route, reclassifying ISPs under the auspices of Title II of the Communications Act of 1934, which was originally designed to regulate radios, telegraphs and telephones.

Going another round

So far, the courts have given the Title II classification the nod. But now, with the FCC under new leadership, the debate is back.

On May 18, the FCC voted 2-1 to review the 2015 rules— the first step in the process of repealing and replacing them. Pai called the Obama-era regulations "a bureaucratic straitjacket," according to NPR.

What's not clear is what the replacement would be. There are several options, said Larry Downes, an internet industry analyst and co-author of "Big Bang Disruption: Strategy in the Age of Devastating Innovation" (Portfolio, 2014). The federal appeals court that previously struck down the FCC's non-Title II attempts to regulate ISPs suggested the agency try Section 706 of the Telecommunications Act, which focuses on broadband access but is not as comprehensive as Title II. That would be one option for removing the utility-like regulations but keeping net neutrality, Downes told Live Science.

However, many net-neutrality advocates think Section 706 isn't strong enough to ensure a neutral internet. [How Big Is the Internet, Really?]

"[S]ection 706 doesn't stand on the solid legal foundation of Title II when it comes to treating internet access providers as common carriers," Timothy Karr, a spokesman for the nonprofit Free Press, which advocates for net neutrality, wrote in an email to Live Science. "Title II has withstood several court challenges to that end. We don't believe section 706 would withstand such scrutiny."

Another possibility is that the FCC will revert back to the pre-2010 status quo, Downes said. Many advocates argue that this would be disastrous for the free flow of data online, but Downes disagrees. Between 1996 and 2015, there was only one court case over an alleged violation of net neutrality, Downes said. (That was the peer-to-peer file sharing Comcast case that killed the FCC's first attempt at regulation.)

"The reason it didn't happen was, the Federal Trade Commission was on the job," Downes said. "It's illegal to discriminate in terms of how we manage internet traffic if you are doing it for anti-competitive purposes."

If the FCC went back to pre-2010 regulations, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) would regain its status as the enforcer of those rules. But the FTC rules are not as strong as the FCC's. One Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals case held that companies that provide internet and also provide a common carrier service (such as phone lines) were exempt from FTC regulation. That decision was recently vacated as the Ninth Circuit will rehear the case, and it is uncertain whether the FTC will ultimately hold on to that regulatory power.

A final option, Downes said, would be to cut off the endless FCC squabbling with congressional action. A new law could give the FCC clear regulatory control over net-neutrality issues without regulating ISPs as utilities, Downes said.

That would be a fight in its own right. Advocates of managing ISPs the same way as utilities argue that ISPs otherwise behave monopolistically, and that consumers end up with poorer, more expensive internet service.

"What really matters is whether, someday, we'll take on as a country the issue of the dismal state of high-speed internet access in America," Harvard Law professor Susan Crawford wrote on the tech site Backchannel. "If the Title II reclassification holds, it's more likely that we will take that step sooner."

Meanwhile, opponents of regulating ISPs the same way as utilities say the extra rules stifle investment and innovation.

"The kinds of things that they [utilities] work for don't really reflect the nature of broadband, which is competitive, which changes all the time, which is consumer-driven," Downes argued.

A congressional battle would probably bring these issues to the forefront. In February 2015, three House members — Reps. John Thune, R-South Dakota; Greg Walden, R-Oregon; and Fred Upton, R-Michigan — released a draft bill that would have enshrined net neutrality into law while otherwise limiting FCC regulation of broadband providers. The draft law never went anywhere. Now, Recode reports that congressional Democrats are planning to take a stand on regulating ISPs, which could be a stumbling block to a bill like the one proposed by Thune, Walden and Upton.

That means the public can expect a lot more uncertainty over internet regulations, no matter how the FCC handles net neutrality this time around.

"Chairman Wheeler said Title II; Chairman Pai said not Title II," Downes said. "Guess what happens the next time a Democrat is the head of the FCC?"

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus