Archaeologists Reconstruct Face of Medieval Man Who Died 700 Years Ago

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

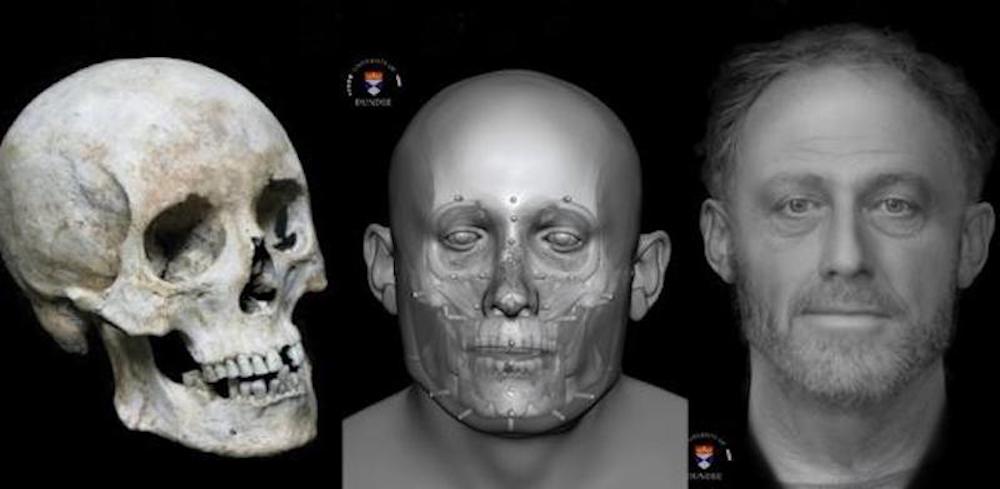

The face of a British man who died about 700 years ago has been brought to life using reconstructive technology.

The medieval man was buried along with hundreds of others in a graveyard underneath what is now the Old Divinity School building of St. John's College at the University of Cambridge, in the United Kingdom. By studying his remains and piecing together his facial features and biological history, archeologists said they hope to understand the lives of anonymous poor people in the 13th century.

"Most historical records are about well-off people and especially their financial and legal transactions," study lead researcher John Robb, a professor of archaeology at the University of Cambridge, said in a statement. "The less money and property you had, the less likely anybody was to ever write down anything about you. So, skeletons like this are really our chance to learn about how the ordinary poor lived." [25 Grisly Archaeological Discoveries]

Most of the skeletons found beneath St. John's were of impoverished adults. Their burials ranged from the 13th to 15th centuries, when the graveyard was attached to a hospital and charitable foundation for the poor and infirm, according to the researchers.

Scientists studied the skeleton of one man, dubbed Context 958, in more detail. Measuring the man's pelvic bones helped the archaeologists conclude that the medieval man was over age 40 when he died. Analyzing the jaw, cheekbones and skull also helped the researchers estimate Context 958's facial structure. And peering into his backbone revealed that he had participated in hard labor, leading to herniated vertebrae and possible chronic back pain.

While the team wasn't able to tell exactly what the man's profession had been, or what ultimately led to his demise, the skeletal clues and sparse grave suggest that Context 958 was a laborer or craftsman of some sort, the researchers said.

"One interesting feature is that he had a diet relatively rich in meat or fish, which may suggest that he was in a trade or job, which gave him more access to these foods than a poor person might have normally had," Robb said. "He had fallen on hard times, perhaps through illness, limiting his ability to continue working or through not having a family network to take care of him in his poverty."While the team wasn't able to tell exactly what the man's profession had been, or what ultimately led to his demise, the skeletal clues and sparse grave suggest that Context 958 was a laborer or craftsman of some sort, the researchers said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Evidence of blunt-force trauma that left a small dent in the back of Context 958's head, and tooth decay that wiped out multiple molars, also provide clues that the man likely had a tough life.

Eventually, Robb's team hopes to compare the Cambridge man's reconstructed biography to those of the other skeletons buried alongside him, as well as remains from other Cambridge graveyards from around the same time. The comparisons may help humanize medieval citizens as people with a variety of life experiences and stories, Robb said.

Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus