Odd Football-Size Armored Creatures Solve Ancient Footprint Mystery

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

In a Cinderella-esque story, researchers have finally figured out the creature that left countless fossilized footprints across the ancient seafloor. The tracks — double grooves filled with scratches made by the creatures' spiny legs — belong to a football-size trilobite that lived about 480 million years ago, a new study reports.

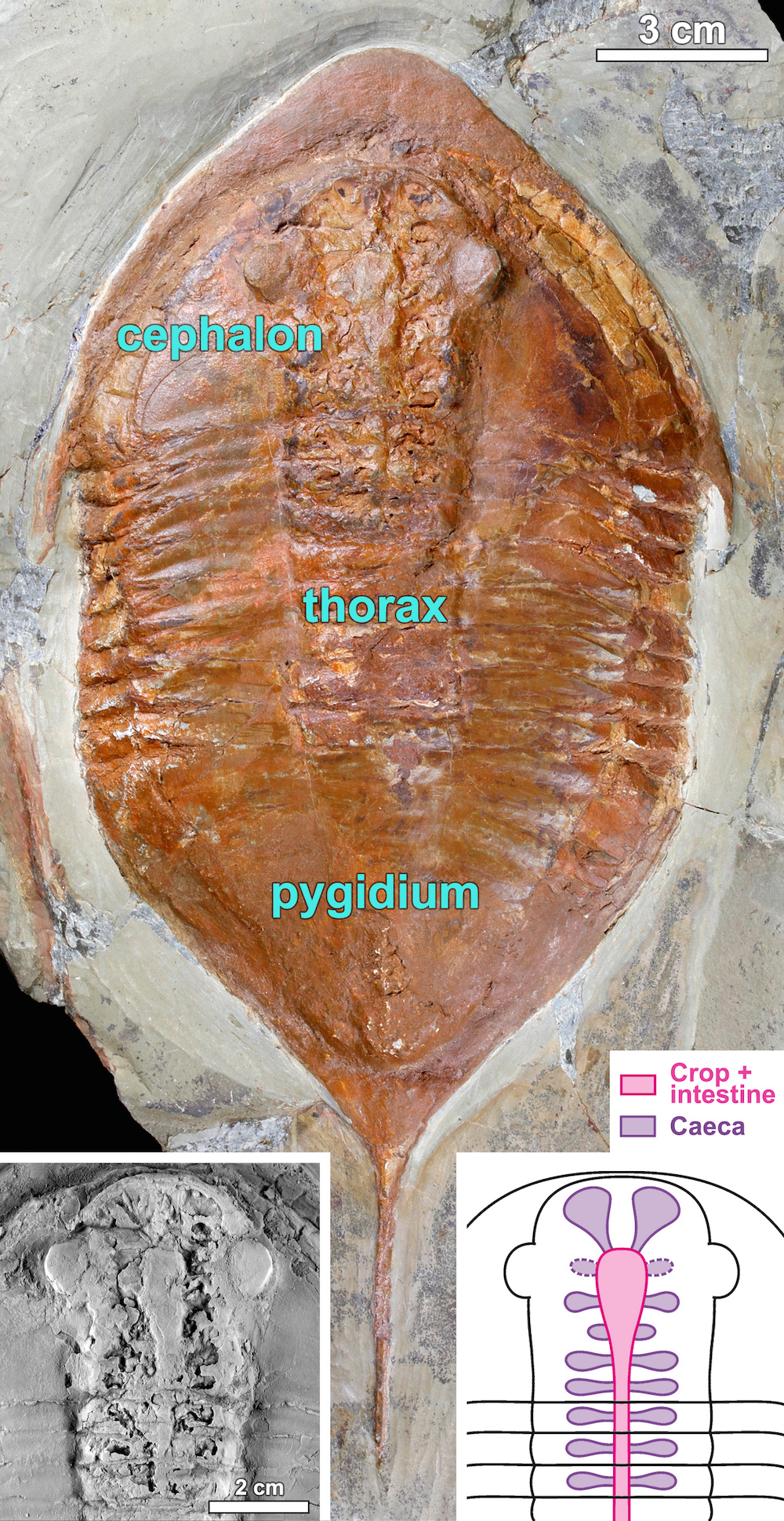

The finding was made possible by the discovery of three incredibly detailed fossils of the trilobite Megistaspis (Ekeraspis) hammondi, the researchers said. Found in Morocco, the three Ordovician-period fossils preserve the remains of the animals' legs and some of their soft parts, including their digestive tissues, they said.

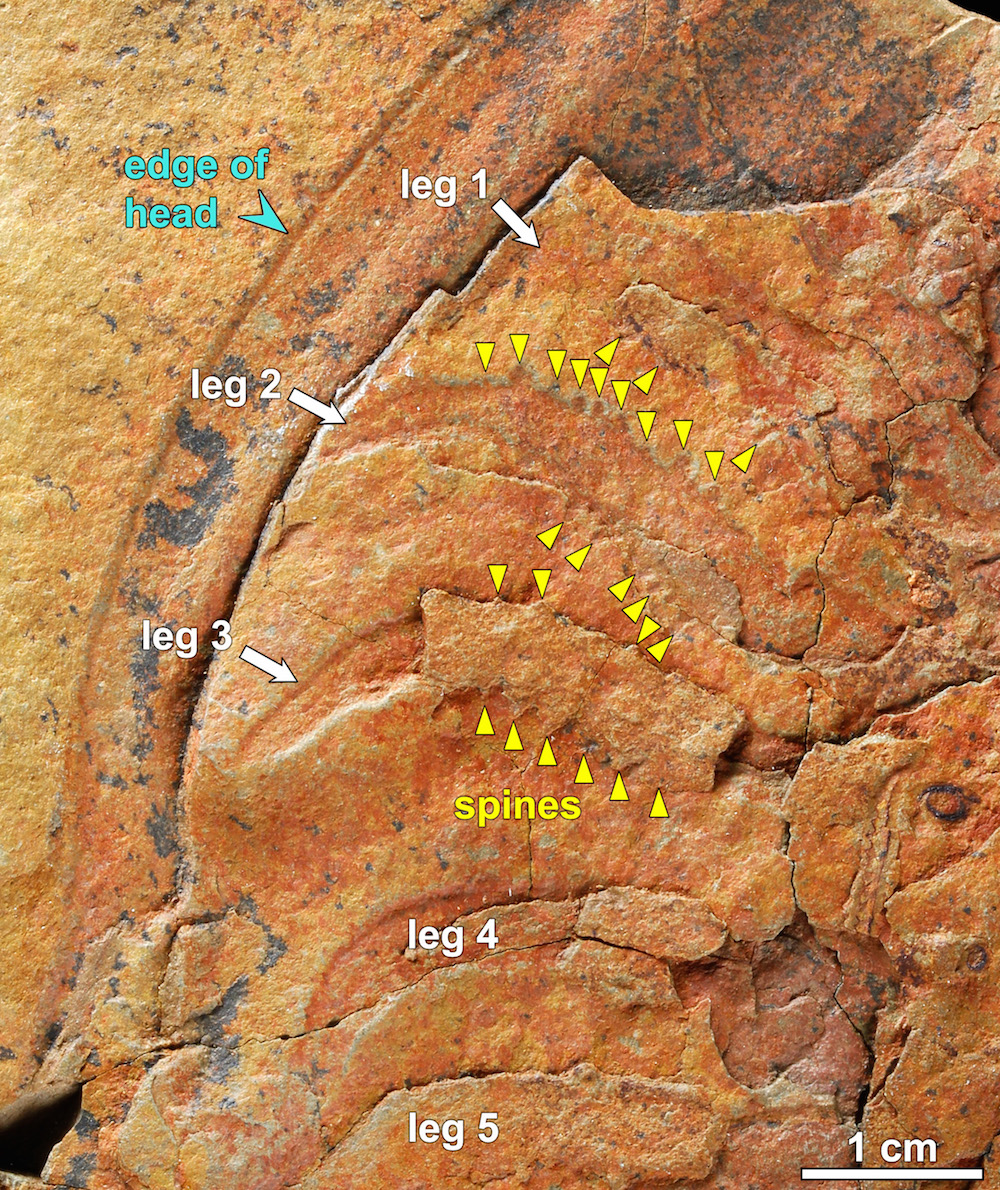

"One of the most striking aspects of the discovery is that the first three pairs of legs, those located in the head, bear short, strong spines, while those farther back in the thorax and tail are smooth," Diego García-Bellido, ARC future fellow with the University of Adelaide's Environment Institute and South Australian Museum, said in a statement. (García-Bellido received a "Future Fellowship" from the Australian Research Council.)

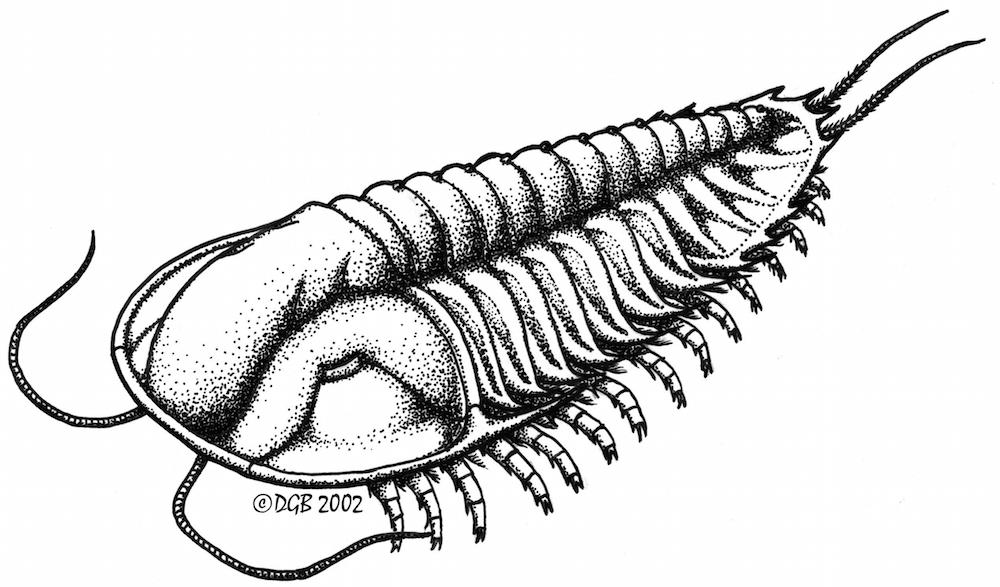

The extinct M. (E.) hammondi were approximately 12 inches long (30 centimeters) when alive and would have scuttled around Gondwana, the ancient supercontinent that included current-day Africa, South America, Australia, Antarctica, the Indian subcontinent and the Arabian Peninsula, the researchers said. [Photos: Trove of Marine Fossils Discovered in Morocco]

Trilobites, sea creatures with hard, calcified armor-like skeletons, were common about 300 million years ago during the Paleozoic Era. They disappeared about 250 million years ago during a mass extinction that killed about 96 percent of all marine species, the researchers said.

The Ben Moula family, who has uncovered countless detailed fossils in the Moroccan desert, collected the newfound remains in the formation called Fezouata Biota, the researchers said. The family sold the specimens to a professional fossil dealer, who offered it to the Museo Geominero, a museum of minerals, rocks and fossils in Spain.

Scientists already knew about the trilobite species M. (E.) hammondi, but the newfound fossils are among the most detailed of their kind on record, the researchers said. For instance, the leg spines helped the researchers connect the species to Cruziana rugosa, the name given to the fossilized footprints.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Cruziana rugosa [was] thought to be from a trilobite, but the actual trace-maker was previously unknown," García-Bellido said. "These marine animals ploughed the sediment in the seafloor for food with their forward legs, while holding their heads tilted downward, leaving behind a double groove with parallel scratches made by the spines on the legs."

C. rugosa imprints can have up to 12 parallel scratches per print. An analysis showed that the three newfound fossils "match the traces we've known as Cruziana rugosa," García-Bellido said.

In addition to the complete set of double-branched legs, the M. (E.) hammondi fossils also have preserved gut tissues, including a crop (an internal pocket that stores food before digestion) and several pairs of digestive glands in the upper portion of the digestive system.

Previously studied trilobite fossils have had either the crop or the paired glands, but not both in the same fossil, the researchers said.

The study was published online Jan. 10 in the journal Scientific Reports.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus