Prehistoric 'Sea Monster' Had More Legs Than Thought

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A 480-million-year-old fossil is giving paleontologists new insights into a sea monsterlike creature called an anomalocaridid, which is an ancestor of modern-day arthropods such as lobsters and scorpions, a new study finds.

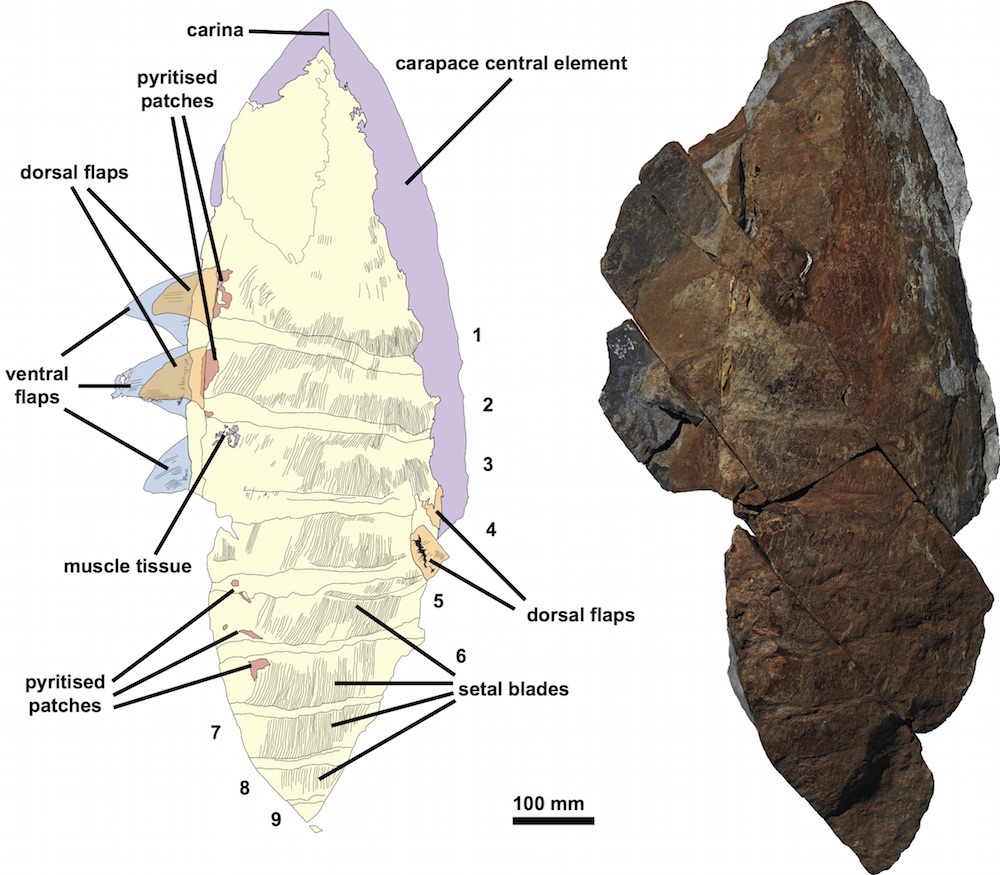

The 7-foot-long (2 meters) fossil reveals that the extinct giant had two sets of legs, not one, as researchers previously thought. It also had a filter-feeding system that likely allowed it to consume plankton, the researchers found.

The researchers named the species Aegirocassis benmoulae after its discoverer, Mohamed Ben Moula, who found the fossil in southeastern Morocco in 2011. [See photos of anomalocaridid fossils and illustrations]

The fossil was "dirty and dusty" when the study's lead researcher, Peter Van Roy, a paleontologist at Yale University, got it into the lab. Van Roy was cleaning the specimen when he realized it had two sets of flaps on each body segment — indicating that the creature had two sets of legs.

"I was totally shocked" to see the two sets of legs, Van Roy told Live Science. "For a week on end, I actually went back to the specimen every day just to look at it again, to make sure that I wasn't seeing things."

The fossil has helped researchers place the anomalocaridid within the arthropod family tree because it gives researchers an unfettered view of the beast, whose anatomy has stumped paleontologists for ages, he said.

Puzzling fossils

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Researchers first identified anomalocaridid fossils in the 19th century, but the creature is so odd-looking — with a whalelike head, bristly appendages and a segmented body covered in flaps — that some people thought the fossilized body parts belonged to several different animals, instead of just one, Van Roy said.

Researchers finally pieced the animal together in a 1985 study published in the journal Philosophical Transactions B. But parts of its anatomy remained a mystery.

"Anomalocaridids seemed to lack front limbs," Van Roy said. "Being an arthropod — being a joint-legged animal — and not having legs, it's kind of embarrassing."

The new fossil helps show that anomalocaridids had two separate sets of flaps per body segment, the researchers said. The upper flap is analogous to the upper limb of modern arthropods, and the lower flaps resembled modified legs that were adapted for swimming. [Cambrian Creatures: Photos of Primitive Sea Life]

"We didn’t know these animals had two sets of flaps (an upper one and a lower one) because the fossils we had were all so flattened," said Greg Edgecombe, a researcher at the Natural History Museum in London, who was not involved in the study.

Van Roy and his colleagues looked back at older anomalocaridid fossils and found they did have the upper and lower flaps seen in the new fossil — showing that researchers had overlooked these limbs in the past.

The finding shows anomalocaridids arose very early in arthropod evolution, Van Roy said.

Filter feeders

The A. benmoulae fossil also shows that the animal was a filter feeder, an animal that strains plankton and other food from the water, much like a modern baleen whale or sponge. Other anomalocaridids from earlier eras were predators that caught prey with their spiny head limbs, the researchers said.

The animal's great size suggests that the oceans had ample plankton during that time, Van Roy said.

The findings are "fantastic," said Javier Ortega-Hernandez, a research fellow in paleobiology at the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom, who was not involved with the study.

"A little over a decade ago, it would have been nearly laughable to think that almost 500-million-year-old arthropods could have reached more than 2 meters in size, and had an ecology similar to that of modern whales," Ortega-Hernandez wrote in an email. "Fortunately, we now have the fossils, and they almost speak for themselves."

The study was published online today (March 11) in the journal Nature.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus