In Photos: Recording the Crackles and Pops from the Northern Lights

Celestial light show

A scientist in Finland has proposed a new theory about the source of the mysterious sounds associated with the northern lights, or aurora borealis.

The sounds, usually described as faint crackling or popping noises, have been reported by many observers and wilderness travelers. But previously, no one has been able to explain how faint sounds from auroras at altitudes of between 60 and 180 miles (100 and 300 kilometers) can be heard on the ground. [Read full story about the sounds from the northern lights]

Flying overhead

Auroras occur when charged particles from a solar flare interact with the Earth’s magnetic field and rain down on the upper layers of the atmosphere. The hot particles excite the gases in the air, causing them to glow in characteristic colors: green and orange-red from oxygen, and blue and red from nitrogen.

This photograph, taken by astronaut Scott Kelly from the International Space Station, shows a bright aurora australis, also known as the southern lights, which occur within the Antarctic circle.

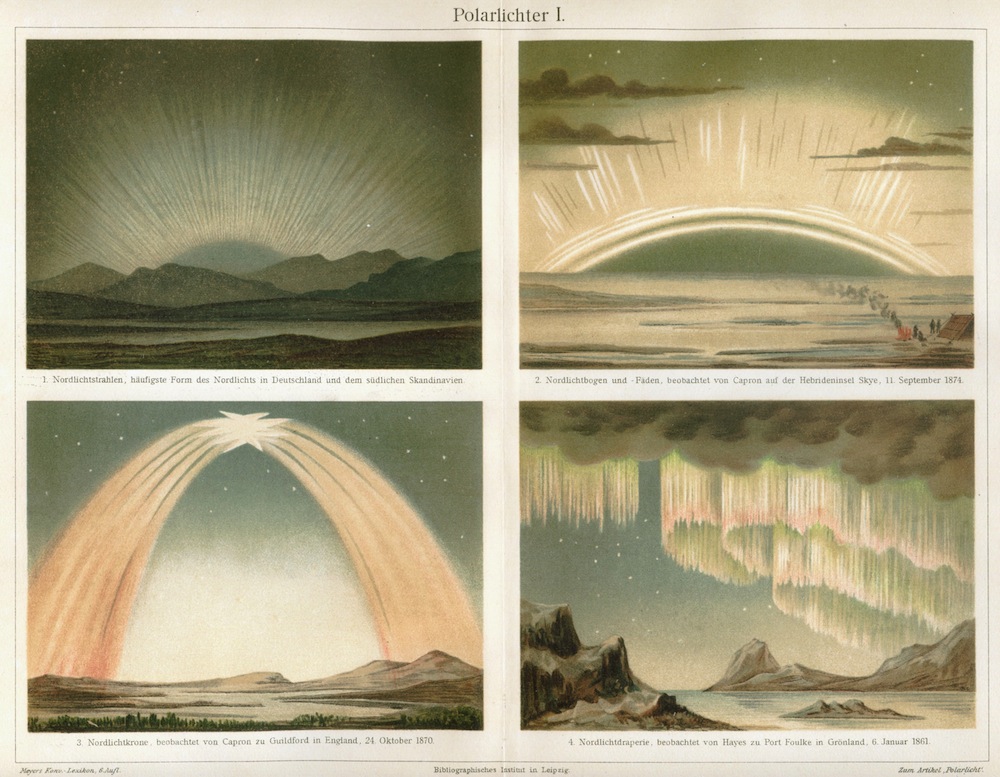

Historic sightings

Auroras are most common in the far north of the Northern Hemisphere, but they are sometimes visible much further south.

In 349 and 344 B.C., the northern lights were observed in Greece and were described by the philosopher Aristotle as resembling flames of burning gas.

These lithographs from a 19th-century German encyclopedia depict the northern lights — called "Polarlichter" in German, meaning "Polar Lights" — for readers before photography was common.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In the field

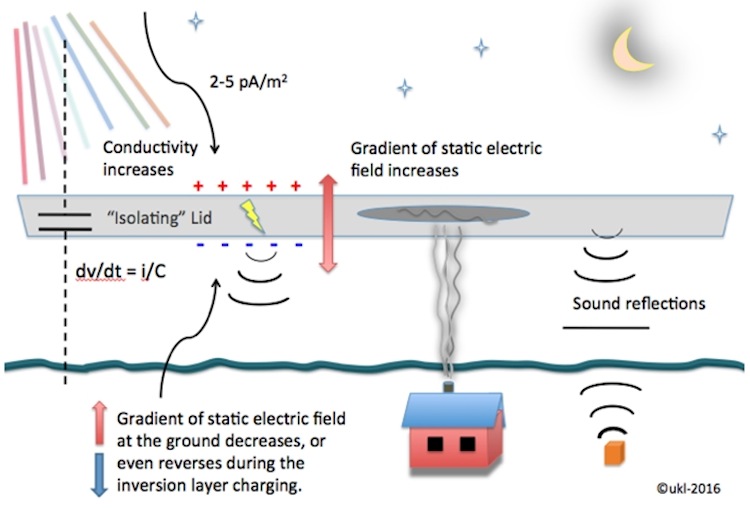

Physicist Unto K. Laine thinks the sounds are caused by electrical discharges low in the atmosphere, sparked by geomagnetic disturbances from the aurora overhead.

Laine has studied the sounds made by the northern lights for more than 15 years, in fields and on frozen lakes near his home in southern Finland. He uses a microphone array to triangulate the location of aurora sounds and a VHF-loop antenna to record magnetic field changes caused by the aurora.

Mystery solved?

Laine has found that aurora sounds originate very low in the atmosphere, about 230 feet (70 meters) above the ground.

His latest research proposes that the sounds are caused by static electricity that builds up in a thermal inversion layer in the atmosphere, which can form in very clear and calm weather conditions. When an aurora occurs over an inversion layer, the geomagnetic storm disturbs this layer of electrical charges, and they discharge as sparks that can be heard on the ground below, Laine said.

Recording the auroras

For his latest research, Laine recorded hundreds of distinct auroral sounds during an intense northern lights display over southern Finland in March 2013, when the overnight temperature was minus 4 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 20 degrees Celsius).

He also measured magnetic pulses that occurred immediately before each sound event that corresponded in strength with the volume of the sounds. On the same night, the Finland Meteorological Institute measured a thermal inversion layer over the region at the same height as the aurora sounds.

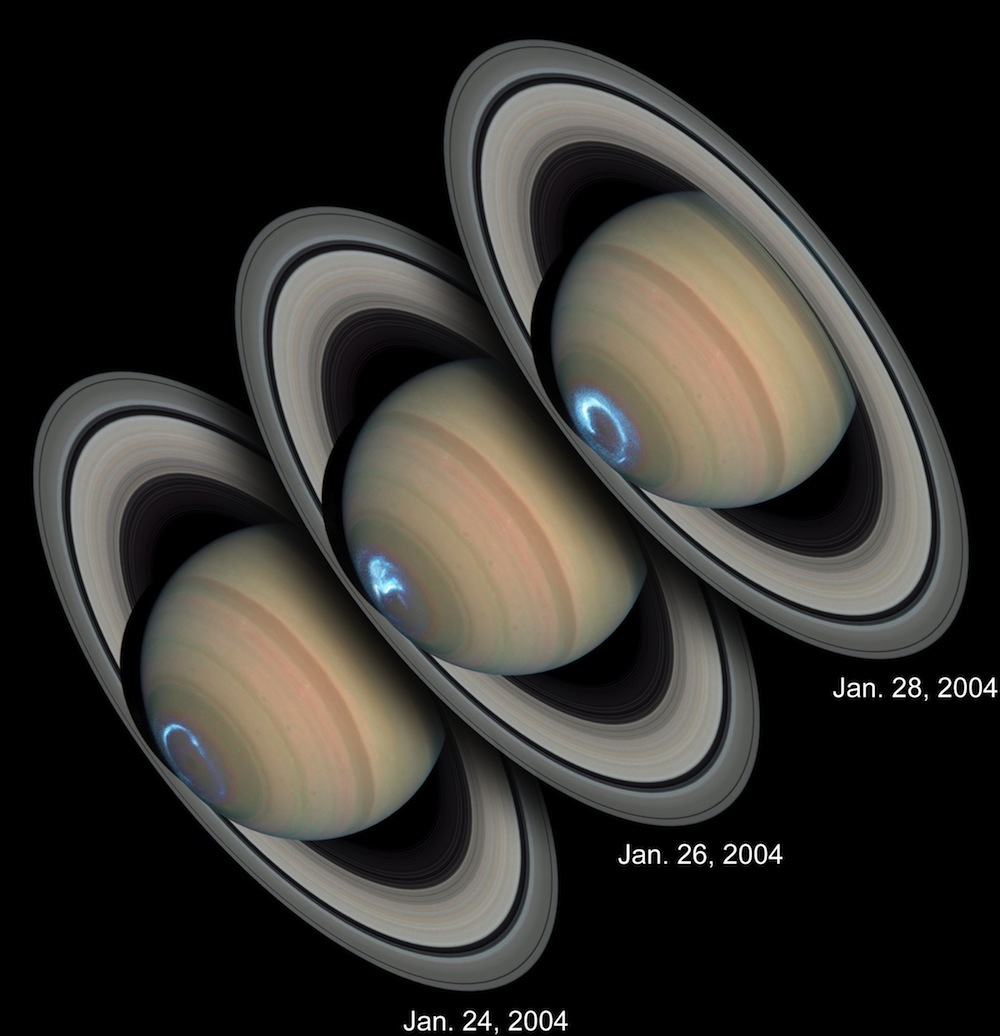

Saturn's auroras

Earth isn't the only planet that has auroras; they occur on other worlds with magnetic fields and an atmosphere. Auroras on Mars are colored blue from hydrogen in the Red Planet's upper atmosphere.

Very strong solar storms can spark auroras in the gas giants of the outer solar system, such as these auroras at the south pole of Saturn in 2004.

Eavesdropping on auroras

Professor Laine setting up his aurora recording equipment on a frozen lake in southern Finland.

Keeping watch

The frequency and intensity of auroras depends heavily on the activity of the sun, which cycles over an 11-year period.

In 2016, the sun is near the peak of its current cycle of activity, and the number of auroras will start to decline again over the next few years. Before then, Laine hopes for several more chances to study the elusive sounds of the northern lights.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus