These Ducks Aren't Lame — They Can Think Abstractly

They're cute, they're fuzzy, they're…abstract thinkers? Ducklings can wrap their tiny brains around ideas like "same" and "different" even when they're scarcely more than 24 hours old, a new study finds.

Previously, it was thought that only animals with advanced intelligence were capable of grasping abstract concepts like these, and then only after a significant amount of training.

In a new study, newly hatched ducklings were shown paired objects that either matched each other in shape or color, or differed from each other. The researchers found that the ducklings were able to recognize and respond to other objects that were similarly grouped, a mere 30 minutes later. [10 Amazing Things You Didn't Know About Animals]

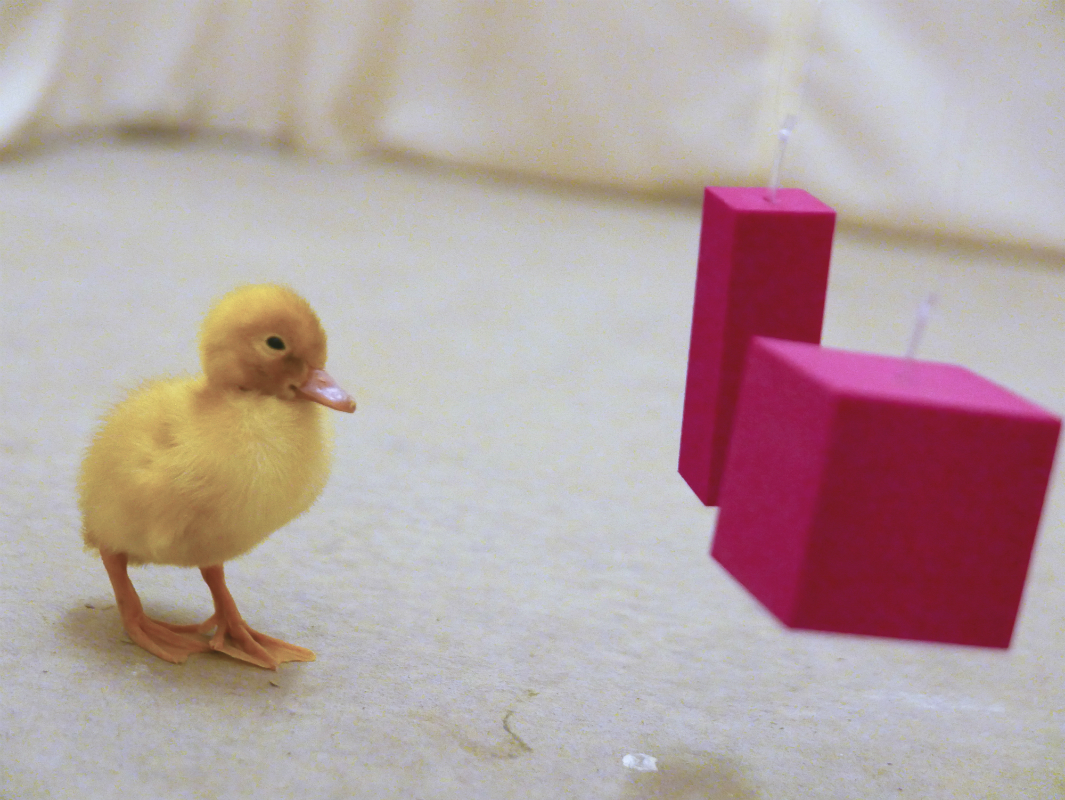

The scientists tested the ducklings by taking advantage of an early-life learning process that is well-known in ducks and other types of birds, called imprinting. During imprinting, newborn animals focus their attention on the first nearby object they see, touch or hear — usually a parent — and then follow that object until they become self-sufficient.

Researchers tested 152 ducklings in two sets of experiments, imprinting them on sets of objects approximately 24 hours after they had hatched.

In the first experiment, the objects were all red, but some were differently shaped. The shapes in the second experiment were all spheres, but some were different colors.

Half the ducklings in both experiments were shown objects that matched in both shape and color, and half imprinted on objects that were different from each other, in either shape or color.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

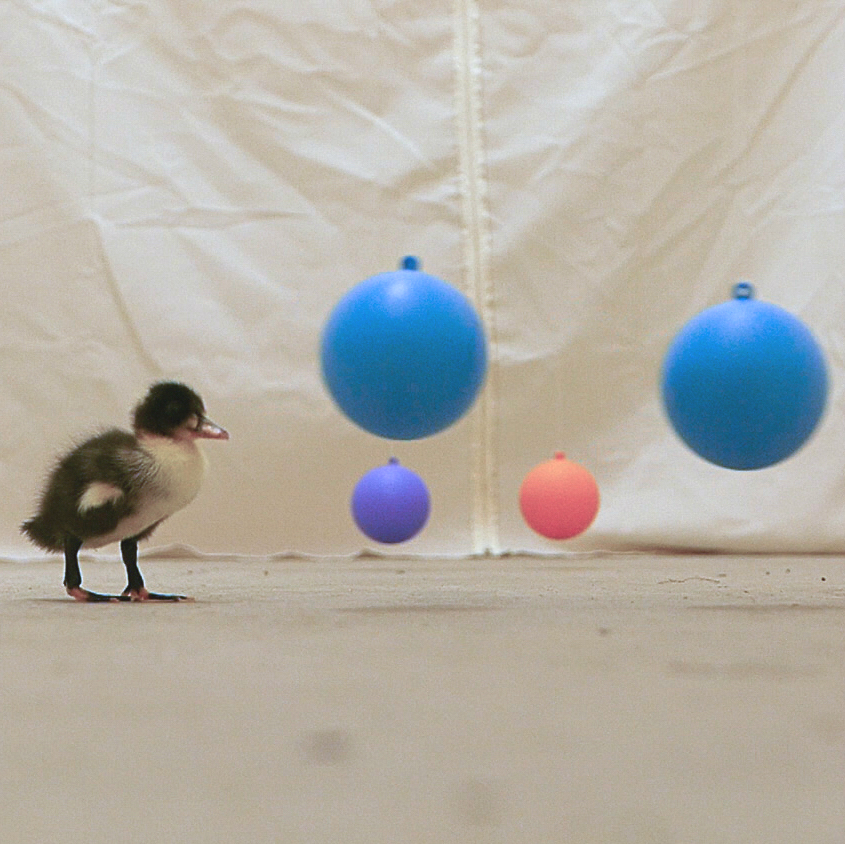

About 30 minutes after imprinting, the scientists showed the ducklings other sets of objects — some of which matched each other, like the set they imprinted upon, and some of which didn't — suspended by wires from a rotating mechanism.

For the first experiment, 32 out of 47 ducklings followed the objects that matched the shape relationship of their imprinted objects — two identical shapes, or two different shapes. For example, if a duckling imprinted on two spheres, it would follow two identical prism shapes in the test, rather than two mismatched shapes.

During the second experiment, 45 out of 66 ducklings chose to follow objects that mimicked the color relationship of their imprinted objects — two identical colors, or two different colors. If a duckling imprinted on two blue spheres, it would follow two green spheres, rather than a pair of spheres that were different colors.

Altogether, about 68 percent of the ducklings recognized and followed pairs of objects that may not have looked exactly like their imprinted object pair, but reflected the same abstract idea — "same" or "different."

Imprinting is thought to represent a very simple type of learning, according to the researchers. Their findings suggest that even this basic form of cognition may be more complex than expected, and animals thought to be not especially intelligent may actually be capable of abstract reasoning, the study authors said.

The findings were published online today (July 14) in the journal Science.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus