Live Crocs Invade NYC in New Museum Exhibit

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

NEW YORK — The decades-old rumors of alligators inhabiting the depths of New York City's sewer system are no more than urban legends. But live alligators have, in fact, temporarily taken up residence here on Manhattan's Upper West Side, in a new museum exhibit.

Beginning this Saturday (May 28) at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), visitors can get up close and personal with crocodylomorphs, the ancient and intriguing animal lineage that includes modern crocodiles and alligators.

The new exhibit, "Crocs: Ancient Predators in a Modern World," introduces the biology and evolutionary history of the animal group, which emerged about 200 million years ago. Crocodylomorphs are archosaurs — a group that includes pterosaurs and dinosaurs. Their contemporary descendants — crocodiles, alligators, caimans and slender-snouted gharials — are known collectively as crocodilians. The exhibit offers a glimpse at the past and present adaptations and lifestyles of these predators, fossils of which have been found on every continent on Earth — even Antarctica. [Crocs: Ancient Predators in a Modern World (Photos)]

Modern crocodilians vary greatly in size, from Cuvier's dwarf caiman (Paleosuchus palpebrosus), which measures about 4 to 5 feet (1.2 to 1.5 meters) in length, to the saltwater crocodile (Crocodylus porosus), which can grow to be more than 15 feet (4.6 m) long. Life-size models of these and other species are presented in the exhibit in dioramas — undeniably the safest way to closely observe physical features of these toothy beasts.

Tremendous diversity

Whether big or small, all crocs inhabit similar environments — areas close to the water's edge in both marine and freshwater habitats — and share a similar body plan: a scaly, armored trunk built close to the ground; short, stocky legs; elongated snouts; and muscular tails.

Their extinct ancestors exhibited a greater variety of forms — there were dolphin-like swimmers and ambush predators that never went in the water, short-snouted plant eaters, and insect eaters that leaped to catch their prey, according to Mark Norell, the exhibit's curator and chair of the AMNH's Division of Paleontology.

"Some looked like cats," Norell told Live Science. "Some were armored, like armadillos. Some were thought to be tree climbers. Some were bipedal, or had hoofs. Some had no teeth. There's a tremendous diversity of these animals that existed in the past."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

These extinct crocs, with their wide variety of body shapes, are thought to have been outcompeted by dinosaurs, Norell said. And while modern crocs may present a less diverse range of physical features, they are still full of surprises that will challenge visitors' expectations, he added.

Norell told Live Science that because crocs originated alongside dinosaurs, people may be tempted to think of them as primitive reptiles. But the truth is that crocs have advanced sensory systems and are highly adapted for different habitats and for hunting different types of prey.

"These animals are fantastically specialized," Norell said. "They might physically resemble something that lived in the distant past, but metabolically, they're quite different. They're not just relics of the dinosaur era." [Alligators vs. Crocodiles: Photos Reveal Who's Who]

"Typical babies"

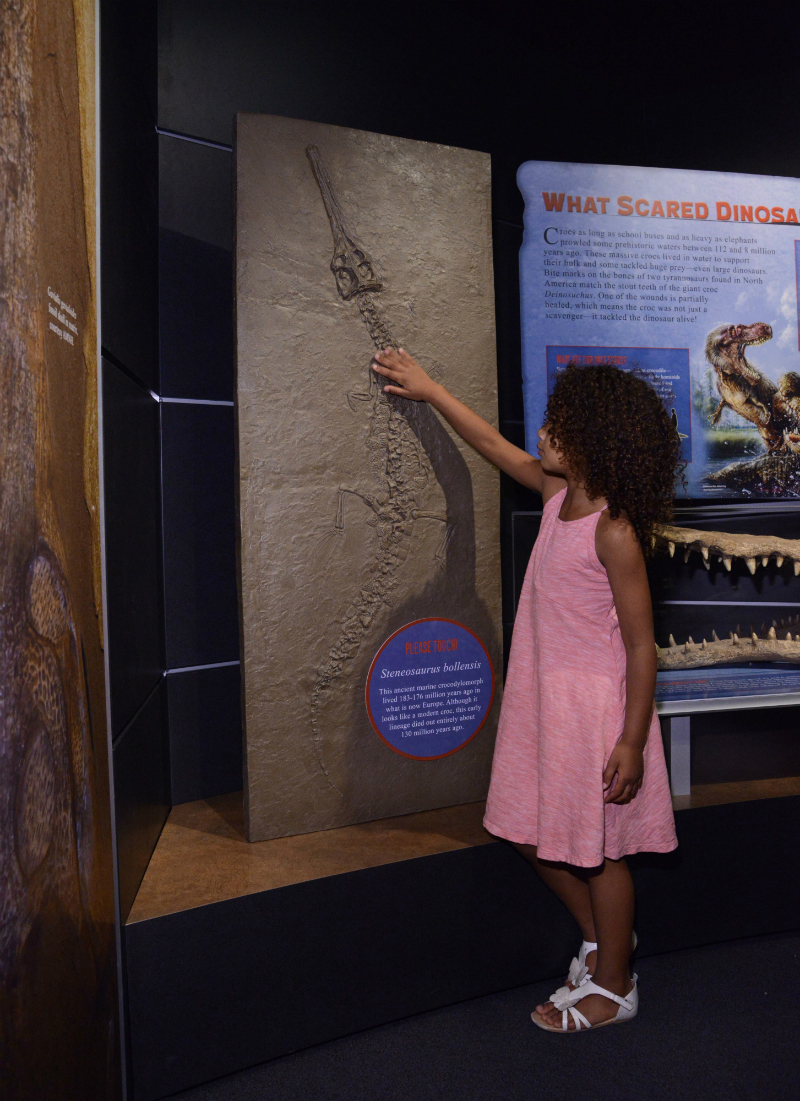

Life-size models of crocs crouch in habitat settings, introducing a handful of the species that share our world today, while hands-on activities invite visitors to touch replicas of snouts and skulls, explore the sounds crocs make, and try a strength test that approximates the force of a croc's powerful bite.

Live crocodilians also make an appearance, with four species represented. Unquestionably the most endearing are the highly active half dozen American alligator hatchlings, which are about six months old and currently measure about 15 inches (38 centimeters) in length. Hazel Davies, who manages living exhibits for the AMNH, described them as "typical babies," swimming around and exploring their habitat. Young alligators grow rapidly: Davies estimated that the gator "babies" will likely be about 3 to 4 inches (8 to 10 cm) longer by the end of the exhibit's run.

"So they're not going to get huge," she said. "Thank goodness."

But as big as they may grow in the wild, these and other crocs today still face challenges that their ancestors never did: human activities such as hunting and habitat destruction.

George Amato, director of the Sackler Institute for Comparative Genomics at the AMNH, has conducted DNA analysis of crocodilian skin samples to help government agencies identify whether endangered species were targeted by the illegal wildlife trade. Amato told Live Science that protecting crocodilians is important not only to preserve threatened species but also to maintain the overall health of their ecosystems.

"Crocodilians are usually the top predator in their environment," Amato said. "And as such, they help structure their ecosystem. If you want to conserve an intact ecosystem, they have a big impact."

Feeling the heat

Climate change is also a looming threat to modern crocs, said Evon Hekkala, a research associate with the AMNH herpetology department. Hekkala uses DNA extracted from archived specimens in museum collections to study how populations of crocodiles have changed over the past few centuries.

Hekkala said crocs may be particularly vulnerable in a warming world because the sex of their young is determined by the temperature of the incubated egg.

"There's a lot of research right now trying to model what would happen if we have a 4-degree [Fahrenheit] temperature increase, and how that would affect populations of these species," Hekkala said.

"On the other hand, their ability over the last 12 million years to move around the planet and to colonize habitats — freshwater and saltwater — may indicate that they have certain innate resilience that we can learn from," she added.

Follow Mindy Weisberger on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus