Lost Wright Brothers' 'Flying Machine' Patent Resurfaces

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The patent file for the Wright brothers' original "Flying Machine" has returned to the National Archives, after being misplaced 36 years ago.

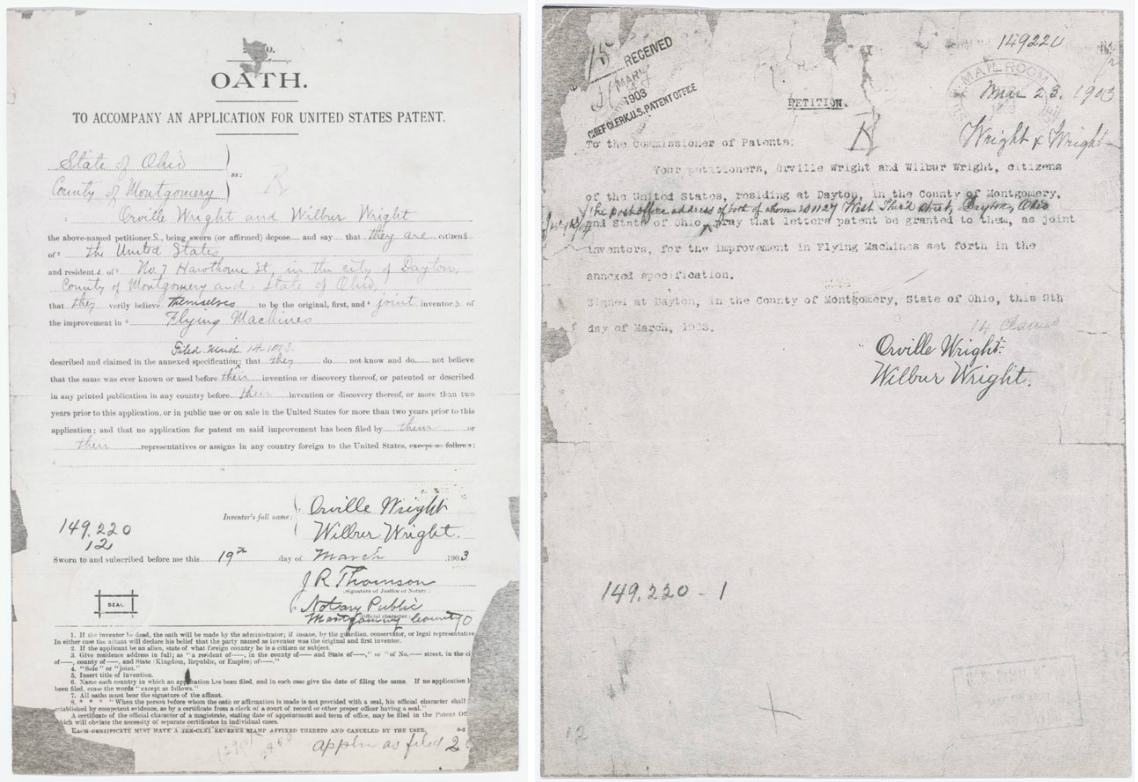

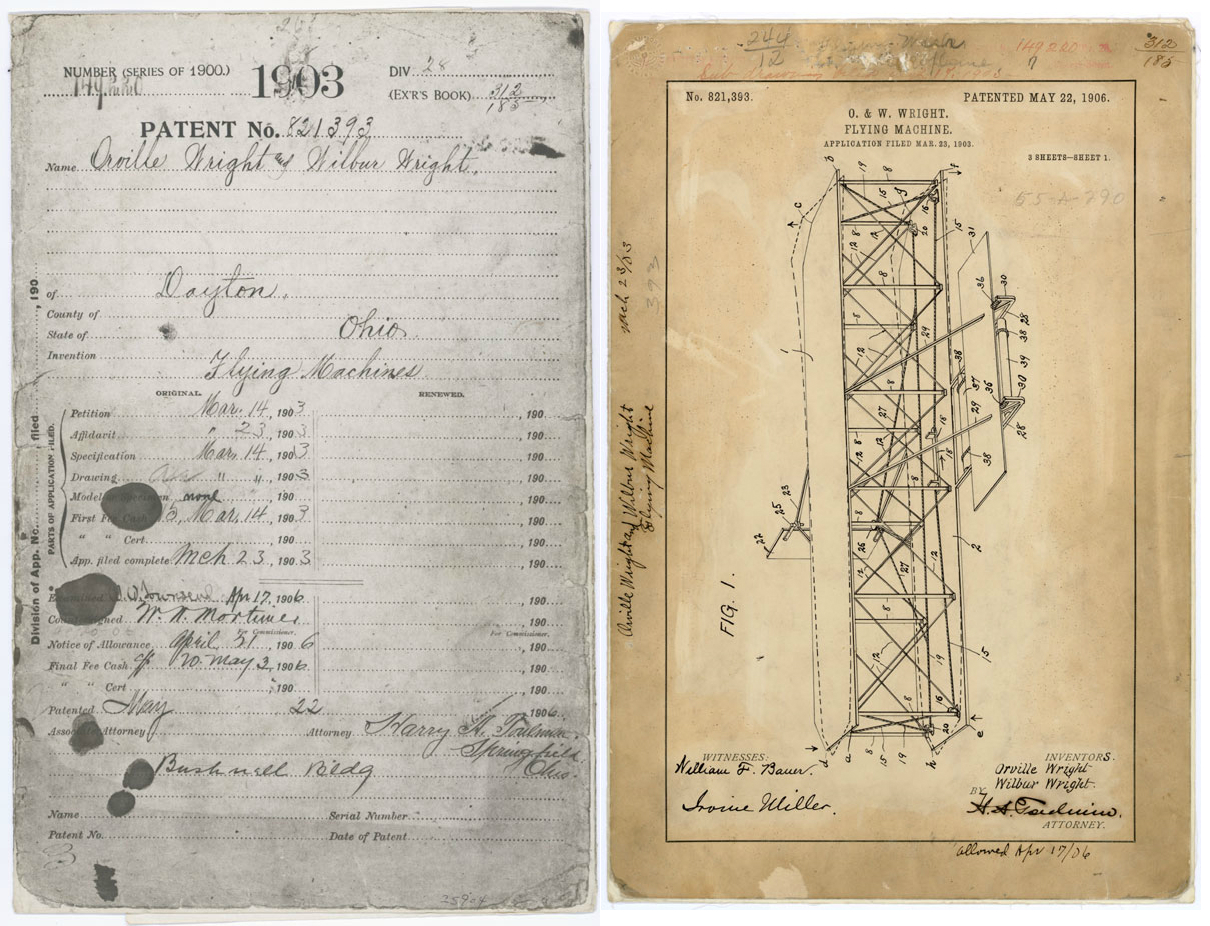

The long-missing patent paperwork filed by aviation pioneers Orville and Wilbur Wright on March 23,1903, included a diagram of their invention, their petition for patent approval, the patent registry form, and their patent oath, affirming that "they verily believe themselves to be the original, joint inventors" of the so-called "Flying Machine."

The Wright brothers didn't wait for the patent to be granted to take flight. On Dec. 17, 1903, the brothers lofted their flying machine into the air for 12 seconds, flying 120 feet at Kitty Hawk, on North Carolina's Outer Banks. And a little more than three years after filing, the Wright brothers were granted their patent: number 821,393, assigned on May 22, 1906.

A wrong turn for the Wright patent

For years, the files resided in the National Archives in Washington, D.C., the federal repository for historically important U.S. documents.

But more than three decades ago, the Wright patent took a wrong turn, embarking on an unexpected journey that diverged from its proper place for quite a bit longer than expected.

In 1978, the National Archives lent a number of documents — including the Wright brothers' patent — to the Smithsonian Institution’s Air and Space Museum, for an aviation exhibit commemorating the 75th anniversary of the first successful flight of a manned, powered, heavier-than-air craft at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Archivists marked the documents as returned in 1980, but a later search failed to locate the patent, and it was added to the official list of missing files. Other important entries currently on the National Archives "Missing Historical Documents and Items" list include the patent drawing for Eli Whitney's cotton gin, assorted 19th-century presidential pardons, several telegrams written by President Abraham Lincoln, and a diamond-studded dagger that was given to President Harry S. Truman.

Sometimes, historic documents and artifacts are stolen for private sale, and the National Archives exhorts collectors and dealers to avoid illegally buying, selling or trading in stolen government documents, and to report any that they might encounter to the proper officials.

But important documents can also simply be misplaced. With more than 107,600 cubic feet (3,047 cubic meters) of patent files in storage at the National Archives, containing 269 million pages, it's not very difficult to imagine how a single patent could "disappear" if it were mistakenly filed in the wrong spot.

Which is apparently what happened to the Wright brothers' patent. A National Archives representative revealed in a statement that the patent had been filed in the wrong box, and that the Archival Recovery Program tracked it down on March 22, after a targeted search. A folder holding the missing documents had surfaced in a National Archives storage "cave" in Lenaxa, Kansas, The Washington Post reported on April 2.

After spending more than three decades in hiding, the recovered documents will be getting some long-overdue attention. Several pages will appear in an exhibit at the National Archives Museum's West Rotunda Gallery, beginning May 20, to celebrate the 110th anniversary of Orville and Wilbur Wright receiving patent number 821,393.

Follow Mindy Weisberger on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus