5 Ways Science Could Make Football Safer

Bone-crunching hits and flying tackles are part of what makes football fun to watch, but they are also part of the reason the sport is now facing scrutiny over the serious head injuries that it can bring.

Now, in response to concerns from the public and players about injuries, research into making football safer has become a leading topic of discussion for the NFL and many sports medicine organizations, experts say.

An investigation published last week by The New York Times revealed that concussion research from the National Football League (NFL) was incomplete to the point of being misleading. According to the Times, data that the NFL used in 13 peer-reviewed articles, which supported the NFL's claims that brain injuries from football cause no extended harm to players, left out over 100 diagnosed concussions, including the injury that ended the career of Steve Young.

The Times concluded that the league's database was compiled to make concussions seem less frequent than they actually were.

Meanwhile, recent research has suggested that concussions may increase the risk of health problems later in life, specifically, cognitive decline that may be linked to the development of dementia. Here are some changes to the game that researchers and scientists think could reduce concussion risk in football.

1. Define concussions

There are currently no standardized criteria for diagnosing concussions. Symptoms can be wide-ranging, including problems with vision, hearing, memory, focus and coordination. They can vary in intensity and may not be noticeable until days after the injury. [10 Things You Didn't Know About the Brain]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Most [doctors] accept a headache after a potential head injury as a 'concussion' or 'mild traumatic brain injury,'" said Dr. Jamshid Ghajar, a neurosurgeon and director of the Stanford Concussion and Brain Performance Center. "However, headaches are not specific to brain trauma — 90 percent of [the] public have headaches at least once annually," he said. This lack of consistent concussion diagnosis standards likely leads to the underreporting of concussion.

Researchers are currently trying to create objective criteria for concussion diagnosis, Ghajar told Live Science. Problems with attention or balance impairments following a blow to the head will likely be part of the criteria, he said.

2. New helmets

Improved designs for helmets are receiving much attention in concussion prevention research. For example, the $1,500 Vicis Zero1 helmet is designed with a soft outer layer that crumples (and bounces back) after impact. The crumple zone slows down an impact.

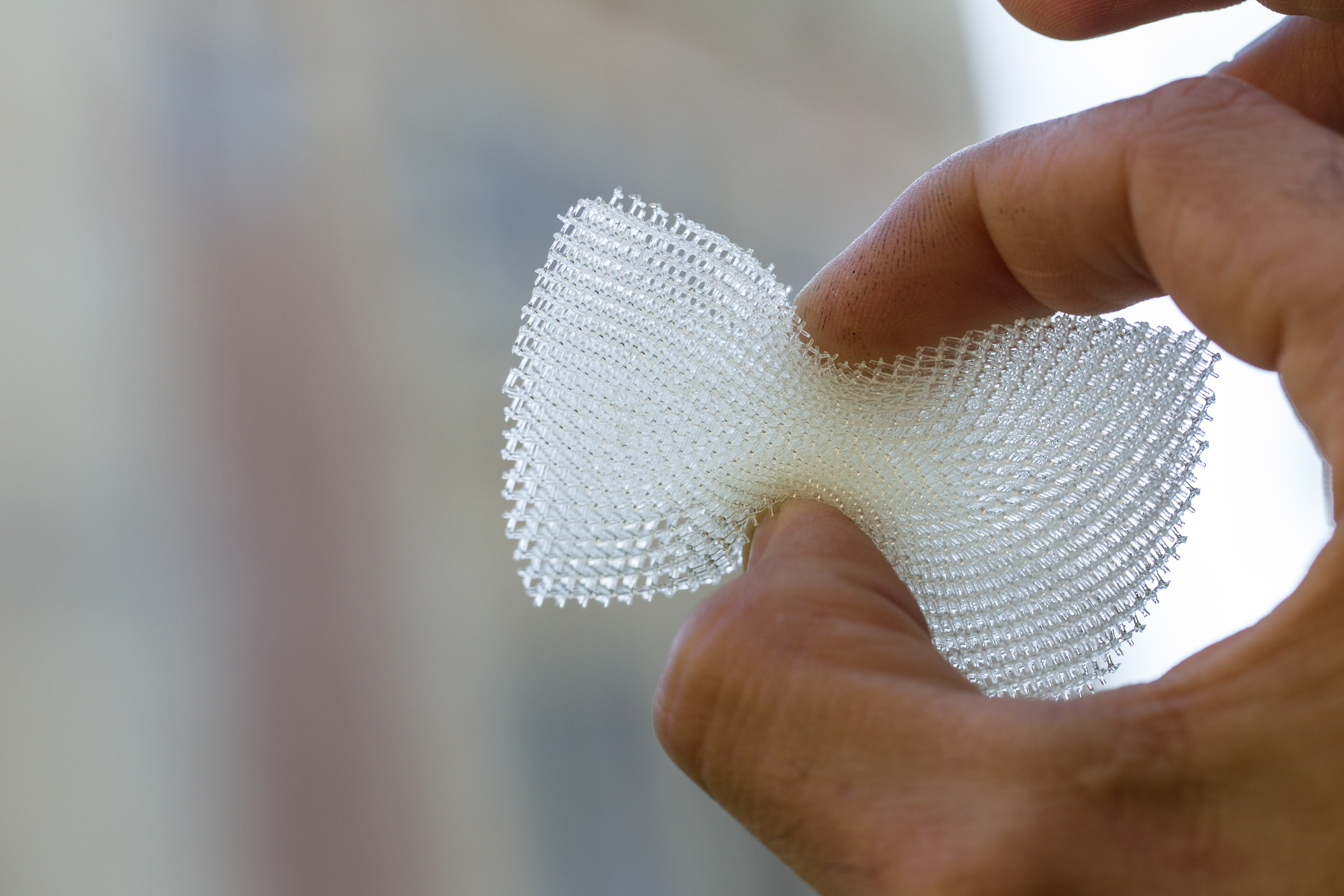

And researchers at UCLA are working on an energy-absorbing microlattice material, called Architected Lattice, that would replace the foam inside football helmets and absorb some of the energy from impacts. This lattice has been shown to reduce peak impact force by 26 percent compared to the conventional foam now used in football helmets, said Larry Carlson, director of advanced materials at the UCLA Henry Samueli School of Engineering and Applied Science and part of the team developing this lattice.

Both of these helmet innovations were Round One winners at the Head Health Challenge II, a contest for researchers working on improving designs, and the Vicis Zero1 was one of the final winners of the contest. But helmets are not going to prevent concussions on their own. Ghajar said their real purpose is to protect against skull fractures and scalp injuries, and that the concussions result from the movement of the neck.

Othe designs for new helmets include a bristly textile with spring-like fibers meant to replace foam in helmets, an internal suspension system that would allow the inner layer of the helmet to move independently of the outer layer, and a multi-layered helmet composed of the traditional polycarbonate shell, flexible plastic, and a material that has the consistency of dried tar.

Erik Swartz, professor and chair of the department of kinesiology at the University of New Hampshire, agreed that helmets and other improvements in equipment will help make football safer. But he also said that sometimes, the line between improving things and making them worse is fuzzy.

For example, helmets that are too heavy could increase the mass of the head and, therefore, acceleration. Soft shells that decrease the magnitude of the force also usually increase the length of time over which that force is applied. Swartz said this could result in an increased risk of neck injury.

3. Neck stabilization

Both Swartz and Ghajar agree that improving neck support is important for reducing concussions in football. "The flexible neck is producing concussions," Ghajar said. Restricting neck motion, or reducing how quickly the neck motion speeds up or slows down, could help prevent concussion, he said. Ghajar pointed to NASCAR's Head and Neck Support (HANS) device, which is a restraint that tethers a driver's helmet to a shoulder harness. This device is not suitable for contact sports, but could give researchers ideas for stabilizing the neck to prevent concussions.

The United States Army Research Lab, in research funded by the Head Health Challenge II, has begun work on a tether system that uses fluid-filled elastic straps to reduce sudden head motion. The straps would attach from a player's waist and torso (via a lightweight harness) to the bottom of his helmet and act like a shock absorber, because the fluid in the straps becomes increasingly solid when stressed.

When force is applied, these tethers harden to increase resistance and decelerate the motion of the head during impact. These are specifically designed to address backward falls. [10 Technologies That Will Transform Your Life]

4. Mouth guards

Some research suggests that football players may reduce their risk of concussion by wearing better mouth guards. For example, a 2014 study published in General Dentistryfound that high school football players who used custom-made mouth guards suffered half as many mild traumatic brain injuries and concussions as those who used over-the-counter mouth guards (3.6 percent versus 8.3 percent). The study included 412 players, 220 of whom were randomly assigned to wear custom mouth guards. However, research published in the American Journal of Sports Medicine in 2014 found the opposite effect: A study of more than 2,000 high school football players found that custom-fitted mouth guards increased sport-related concussion risk by 60 percent, compared generic guards.

Mouth guards can prevent injuries to the teeth, lips, tongue and jaw, but their usefulness in terms of concussion prevention remains unclear. "Use of mouth guards is probably one of the areas that has the least amount of quality evidence," Swartz said. In 2012, mouth guard company Brain-Pad came under fire from the Federal Trade Commission for claims that its product could protect against concussions.

5. Helmetless training

It sounds contradictory, but Swartz's research suggests that having players practice without helmets may make them safer. "We're just trying to take advantage of the vulnerability someone feels [when that person doesn't have] protective equipment on," he said.

Called the Helmetless Tackling Training (HuTT) intervention program, this research consists of having players practice tackling and blocking without their helmets. In one study with 50 University of New Hampshire football players, half of the players were assigned to do 5-minute tackling drills at 50 to 75 percent effort without helmets or shoulder pads, twice a week during the preseason and once a week during the season. Compared to the 25 players who were assigned to practice noncontact football skills in lieu of these drills, the helmetless drill group suffered 28 percent fewer head impacts.

Swartz said his program is currently geared toward studying nonprofessional football, and that the researchers are looking to study youth football next. But helmetless training alone will not solve football's concussion problems, he said. Better equipment and behavior change will both be necessary to address this issue. [Chronic Brain Disease: What's CTE?]

Even with every possible intervention and innovation, short of drastic changes to the game, football players will always be at risk for concussions. For this reason, Swartz cautions against looking too hard for solutions to this problem.

"Concussions happen in football because of the nature of the sport and we shouldn't feel like we have to portray the game as something we can eliminate concussions from or make safe," he said. "In comparison to other sports and other activities, it's not safe. That's the nature of the game."

Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus