Expect Downpours and Flooding As World Warms

Umbrella and galosh manufacturers may do well as the planet continues to warm — if they can find somewhere dry to build their factories.

Findings of a new analysis of storm data and model projections warn that flooding is going to be a worsening problem around the world, with a warmer atmosphere already leading to heavier downpours in both arid and wet climates.

The study identified "robust increases" in "extreme daily precipitation" — the types of drenching storms that can wipe out homes and flood fields.

"The extremes are increasing in both the wet and dry areas," said Markus Donat, a University of New South Wales climate researcher who led the new study, published Monday in Nature Climate Change.

That's likely to lead to more flooding, the researchers noted — though separate research by hydrologists has shown that a long list of other factors will influence how American landscapes will be impacted.

West Likely to Be Stormier With Climate Change Warming Ups Odds And Costs of Extreme U.K. Rains Mud Shortage Eroding California's Climate Defenses

Instead of analyzing the effects of climate change on rainfall in individual regions of the world, Donat's team aggregated the regions into buckets labeled 'dry' and 'wet.' That simplified the statistical analysis, helping to reveal that dry areas are being disproportionately affected.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The group analyzed 60 years of weather observations in the wettest and driest regions, concluding that increases in heavy rainfall events matched simulations made by earth models. Future projections from those same models project that rates of deluges will increase in dry regions more quickly than elsewhere.

Although climate change is often characterized as exacerbating weather extremes, Donat said the findings from the study reject the notion that climate change will reduce heavy rainfall in deserts and other parched areas. "Dry areas also show trends towards more precipitation," he said.

The number of days of extremely heavy rainfall or snowfall has been rising by 1 to 2 percent each decade in the world's driest and wettest regions, the scientists found. Similar increases are projected until 2100.

Climate scientists are warning that the lashings of rain will worsen flooding across the planet.

"This is an important paper, because it shows that when climate models and observations are compared carefully and appropriately, then you see good agreement between them," said Peter Stott, a senior Met Office climate scientist who wasn't involved with the research.

"More intense rainfall projected over the next few decades will lead to more flooding, and challenge our capability to be resilient to a rapidly changing climate," Stott said.

Hydrologists, meanwhile, point out that inland flooding — floods that aren't affected by sea level rise — is caused by a complicated set of factors.

Despite heavier rainfall, there is little evidence so far that floods from such storms are worsening with climate change, said University of California, Los Angeles hydrology professor Dennis Lettenmaier. He said ongoing work is needed to better understand the relationships between heavy rainfall and floods.

"The whole issue of, 'Why aren't floods changing, despite apparent changes in extreme precipitation?' is one that a lot of the climate community has ignored," Lettenmaier said. "Floods are much more complicated than just looking at extreme precipitation."

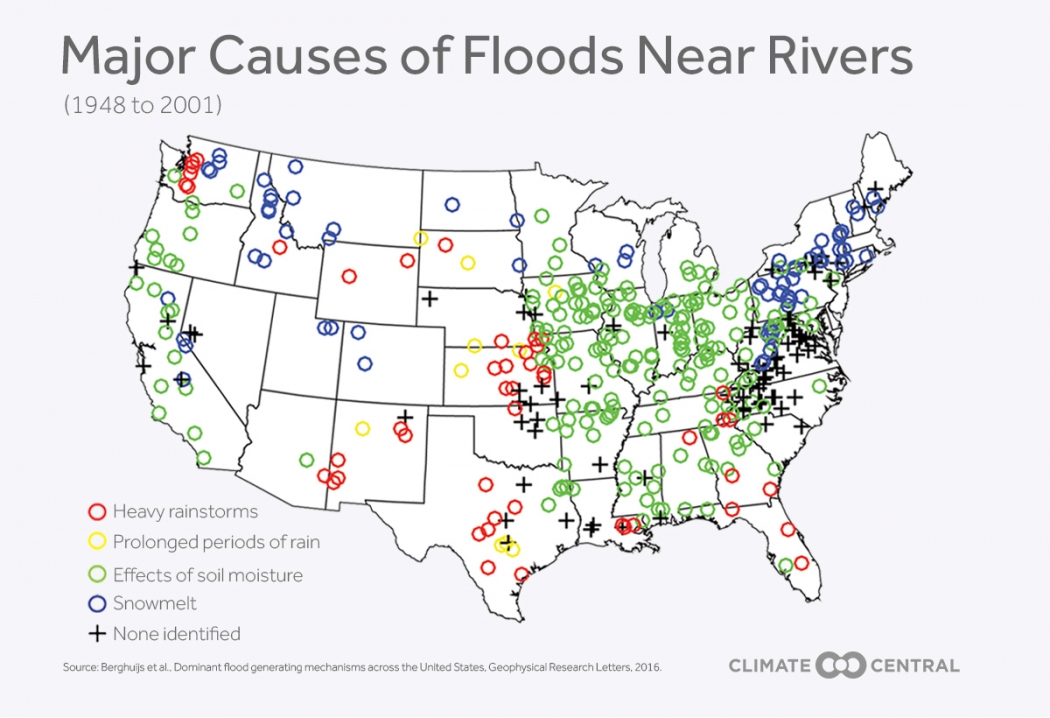

A recent analysis of the main drivers of flooding near rivers, published in Geographical Research Letters, showed that heavy downpours tend to be the major cause of floods in the central U.S., but that other factors are more important elsewhere in the country.

"Especially in the more dry, central parts of the U.S., you find that it’s really the maximum precipitation events which control the flood response,” said Wouter Berghuijs, a hydrologist and PhD candidate at the University of Bristol who led the analysis.

That suggests that the effects of the findings published Monday could be felt most sharply by Americans who are living in the nation’s heartland.

Elsewhere in the country, soil moisture, snowmelt and prolonged raininess were found to be more important factors in determining whether waters would spill out of rivers and into farms and homes.

“Very often, it’s simplified. People say, ‘Well, more extreme precipitation will lead to more extreme flooding,” Berghuijs said. “In the eastern U.S., you should really look into what the soil moisture is doing, too.”

You May Also Like: Utilities Cut Coal Use Amid Clean Power Plan Fight March Miracle? El Niño-Fueled Storms Return to California Another Month, Another Troubling Arctic Sea Ice Record

Originally published on Climate Central.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus