'Space Archaeologists' Show Spike in Looting at Egypt's Ancient Sites

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

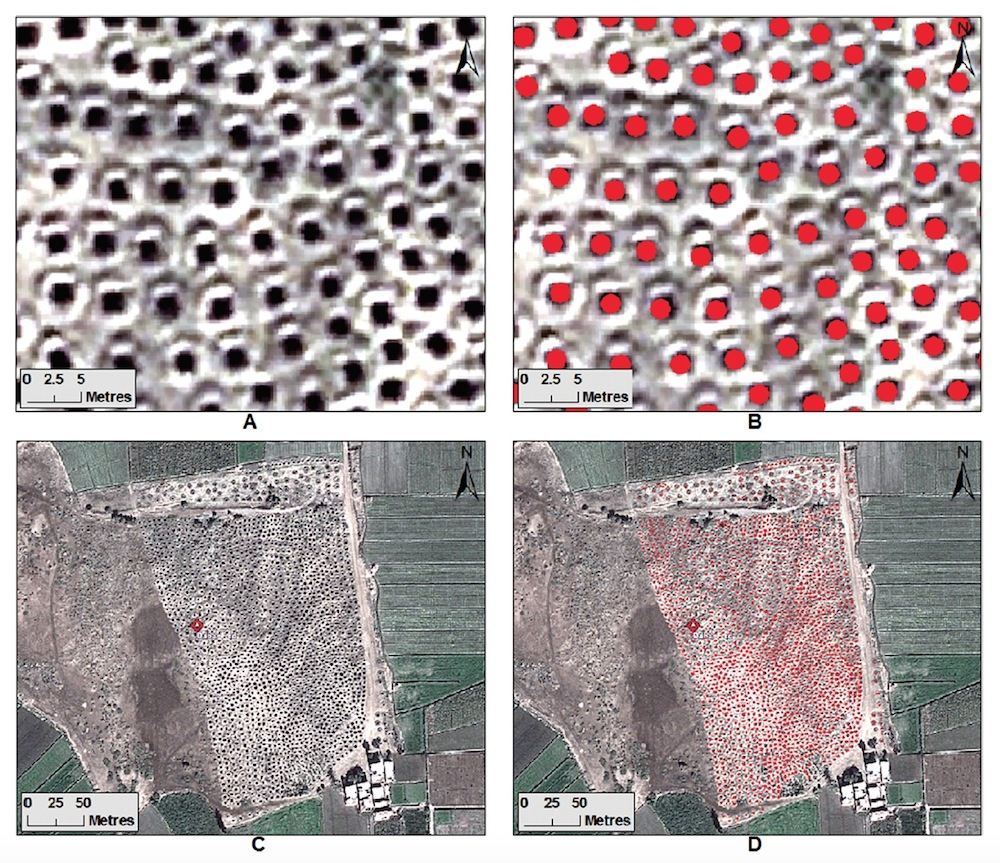

As economic and political instability rocked Egypt, looters increasingly plundered the country's archaeological sites, leaving holes across the nation's ancient landscapes.

That's the trend reported today in the journal Antiquity by archaeologists who used satellite images to monitor sites in Egypt from 2002 to 2013.

For the last several years, "space archaeologist" Sarah Parcak, an associate professor of anthropology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, has pored over satellite images to discover lost pyramids, tombs and cities buried in Egypt. (She's even detected the network of streets and houses of ancient Tanis, the city featured in the Indiana Jones movie "Raiders of the Lost Ark.") In her latest study, Parcak didn't analyze ancient features, but rather looked at modern ones in Egypt: the holes in the ground left by tomb robbers and antiquities thieves. [Reclaimed History: 9 Repatriated Egyptian Antiquities]

"Simply staggering" pits

Parcak and her colleagues looked at satellite images for 1,100 archaeological sites in Egypt's Nile Valley and Delta between 2002 and 2013. The researchers found that the first spike in looting actually came before the political uncertainty of the Arab Spring, the wave of uprisings that began the Middle East and North Africa in 2011. Looting levels at least doubled from 2009 to 2010, in connection with the global economic crisis, and then doubled again from 2011 to 2013, following the revolution that began in Egypt in January 2011.

If looting rates continue at their current rate, all 1,100 sites examined in the study will be looted by 2040, Parcak and her colleagues wrote in the new study.

"The number of looting pits dug during 2009 and 2010 is, in our opinion, simply staggering," Parcak and her colleagues wrote. They counted 15,889 looting pits in their 2009 satellite data, and 18,634 in the 2010 data. For comparison, just 3,247 pits were visible in the satellite data from 2008.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Looting thengrew even worse after the onset of the Arab Spring. On average, the researchers counted 38,000 annual looting pits from 2011 to 2013. Nearly three-quarters of the total damage the archaeologists documented in the study took place during this three-year period.

This trend was borne out at individual sites, such as the area around the crumbling Middle Kingdom pyramid of Amenemhet III at Dahshur, south of Cairo. The site showed no signs of looting in 2009. But by May 2011, satellite images of the same area show a dozen or so looting pits. By September 2012, the site was pockmarked with holes, and by May 2013, the situation was even worse.

When Parcak and her colleagues went to examine the site on foot in December 2014, they saw the looting pits up close. Some of holes were up to 30 feet (10 meters) deep, the researchers said.

What happens after looters find treasure?

Parcak and her colleagues aren't the only ones tracking looting from space; other researchers have applied the same technique to sites in Syria and Iraq, where conflict has left archaeological sites vulnerable to destruction.

"What satellite imagery has done is show us the scale of the problem," said David Gill, a professor of archaeological heritage at the U.K.'s University Campus Suffolk. Gill, who was not involved in the study, noted that the striking images of looting holes should prompt some further questions: How much material must be coming out of these sites, and what's happening to these objects? Are they being stored in warehouses? Or are they entering the market? [In Photos: Amazing Egyptian Artifacts]

Auction data compiled by Gill shows that the total value of Egyptian antiquities sold at Sotheby's in 2002 was about $3 million, but then during the 2009-2010 period, this value was more than $13 million. Parcak and her colleagues noted that the increase in the market mirrors the increase in looting evidenced by the satellite data, which suggests there might be a connection.

"My hunch is that what we need to do is more analysis of what's coming onto the market," Gill said, adding that auction houses and galleries need to have more rigorous "due diligence" tests to authenticate Egyptian antiquities and make sure these objects have legitimate collecting histories. A stricter market might also discourage looters. "If you can't sell it, it's not worth looting."

Satellite imagery could also play a role in the search for illicit antiquities on the art market, Parcak and her colleagues wrote. For instance, if the data from space show that an Egyptian New Kingdom site has been heavily looted, a generalized international watch list could be created to make dealers and auction houses aware of the kinds of mummy masks and other antiquities that should raise suspicion.

The researchers mentioned another needed area of study: on-the-ground ethnographic work to understand who is looting these ancient sites and why. (For instance, are the looters desperate locals or members of opportunistic crime cartels?)

Citizen space-archaeologists

Parcak also wants to enlist members of the public in her fight against art crimes and her quest for undiscovered monuments. She was awarded the 2016 TED Prize, and last night at the TED Conference in Vancouver, she announced what she plans to do with her $1 million award: turn citizens into space archaeologists with a platform called Global Xplorer.

"I believe there are millions of archaeological sites left to find," Parcak said, according to TED. But searching vast areas with satellite data takes a long time. Parcak said she hopes to tackle this problem with a citizen-science platform. Her plan for Global Xplorer is to give citizen archaeologists an online tutorial on how to look for never-before-studied ancient features as well as signs of looting. Then, these participants would be sent a series of satellite images to analyze.

"We'll be treating sites like human patient data, and not revealing GPS points or showing you where your image is on a map," Parcak said. "The data will only be shared with vetted authorities, to create a global alarm system to help protect sites around the world."

The model sounds similar to other crowdsourced projects that have emerged in recent years that ask citizen scientists to do things like count craters on the moon, identify features on Mars, transcribe British war diaries and categorize animals in camera trap photos from the Serengeti. (Those are just some examples from the dozens of projects that can be found on the citizen science portal Zooniverse.)

"A hundred years ago, archaeology was for the rich. Fifty years ago, it was mainly for men. Now, it is primarily for academics," Parcak said in her talk. "Our goal is to democratize the process of archeological discovery and allow anyone to participate."

Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus