Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

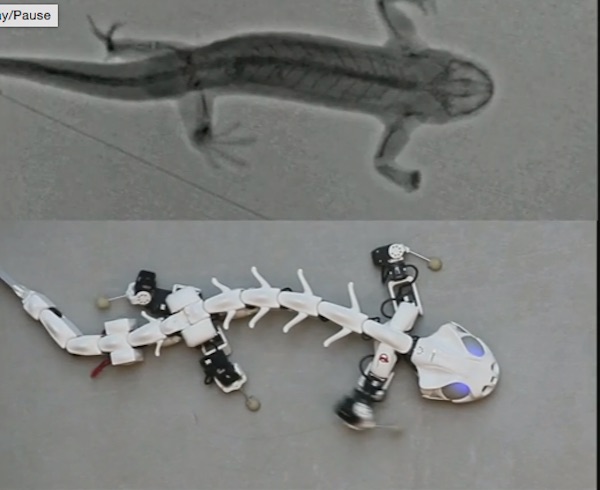

A new salamander robot has been designed that can walk, swim and turn around corners.

The new salamander-inspired bot is helping scientists understand exactly how the spinal cord orchestrates movement.

"We want to make spinal cord models and validate them on robots. Here we want to start simple," Auke Ijspeert, a roboticist at the the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology at Lausanne, said in a recently published TED Talk.

The ultimate goal is to reveal how animals of different types, from primitive lampreys to cats and humans, modulate and control their movement, which could one day help spinal cord injury patients regain control of their lower limbs. [5 Robots That Can Really Move!]

Primitive walkers

To start out, the team decided to model salamanders. From an evolutionary point of view, salamanders are living fossils — quite close in their motion to the creatures that first stepped from the seas onto land. They also switch seamlessly between walking and swimming, Ijspeert said.

"It's a really key animal from an evolutionary point of view," Ijspeert said in the talk. "It makes a wonderful link between swimming, as you find it in eels or fish, and quadruped locomotion, as you see in mammals, in cats or humans."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In the water, salamanders undulate in what's called anguilliform swimming motion. This swimming motion is produced by a continuous wave of motion throughout the spinal cord. When the salamander is on land, it easily switches to a walking trot gait, Ijspeert said.

The researchers found that these two modes of motion are all orchestrated by the spinal cord. For instance, a decapitated salamander still produces a walking gait if the spinal trait is electrically stimulated. Stimulating the spinal cord more, as if "pressing a gas pedal," tells the headless salamander to switch to its swimming gait, Ijspeert said.

Recreating motion

To create the robot, the team first modeled the spinal cord circuits that seem to drive this motion. It turned out that a salamander has essentially kept the very primitive nerve circuits that drive motion in primitive fish such as lampreys, but had simply grafted on two extra neural circuits that control the front and back limbs.

Next, the team used an X-ray video machine to recreate the bone motion of salamanders as they walked and swam. They then identified the most important bones and simulated them in a physical robot.

Amazingly, the robot salamander recreated the walking and swimming gaits almost perfectly, with the spinal cord circuit controlling whether the robot salamander swam or walked. (The robot had to don a "wet suit" to get into the pool.) The team could even get the salamander to turn, simply by stimulating one side of the spinal cord more than the other.

The findings reveal just how well the spinal cord seems to control movement, which seems to be similar even in humans.

"The brain doesn't have to worry about every muscle, it just has to worry about this high-level modulation and it's really the job of the spinal cord to coordinate all the muscles," Ijspeert said in the talk.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus