Sierra Nevada Snowpack Shrinks to Lowest Level in 500 Years

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

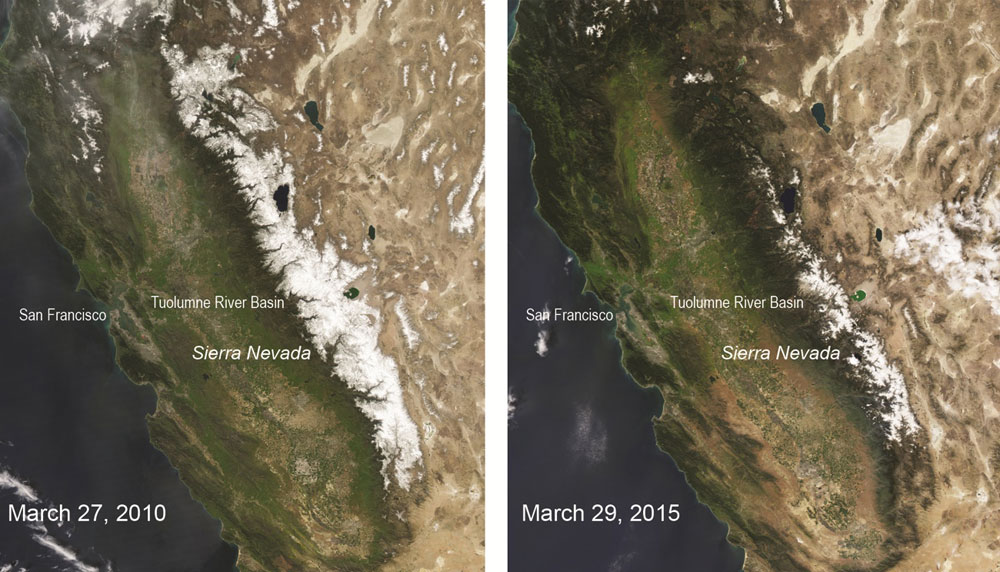

The snowpack in California's Sierra Nevada mountains has reached its lowest point in the past 500 years — primarily the result of the region's dry winter, researchers report.

And the researchers don't expect normal snowpack levels to be replenished anytime soon. "We should be prepared for this type of snow drought to occur much more frequently because of rising temperatures," study researcher Valerie Trouet, a dendrochronologist (a scientist who studies tree rings) at the University of Arizona's Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research, said in a statement. "Anthropogenic [human-caused] warming is making the drought more severe."

According to the US Geological Survey, mountain snow is critical for balance in the natural water system, because the snowpack acts as a natural way to store water. Without this natural balance in the system, dry spells last longer, crop yields suffer and there is less water available for public use. [See photos of the stunning Sierra Nevada mountains]

Snow drought

During the winter months, snowpack typically builds up a large store of water. Then, starting in the spring months, the snowpack melts and helps replenish streams, lakes, groundwater and reservoirs. But when these regions experience a dry winter, like the 2014-2015 season according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration this backup of stored water shrinks.

In turn, less meltwater enters the system during the spring and summer, causing the dry season to extend into the spring, said Lorraine Flint, a hydrologist at the USGS California Water Science Center who was not involved in the new study. Making matters worse, the hot weather means more moisture is sucked out of vegetation, thus creating a greater demand for water, Flint added. [The 10 Driest Places on Earth]

Trouet and her colleagues got the idea for their study after California Gov. Jerry Brown declared the first-ever mandatory water restrictions throughout the state — a result of record-low snowpack that winter and the resulting water scarcity. That made Trouet and her colleagues interested in reconstructing the paleohistory — the study of how something has changed over time — of the Sierra Nevada snowpack.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Tree rings

To do this, the researchers looked at published tree-ring data in central California from 1405 to 2005, which recorded seasonal wet precipitation, rain, and annual snowpack measurements since the 1930s. The researchers also used published reconstructions of winter temperatures in southern and central California from 1500 to 1980.

Growth rings in trees shrink and expand according to the amount of precipitation the tree experienced in the spring, summer, winter or fall, so they are fairly accurate markers of environmental factors like precipitation, temperature and sunlight that affect vegetation growth. Scientists have a particularly long and well documented record of this region's blue oak (Quercus douglasii) tree rings dating back to 1405. Blue oaks also live in regions that get water from the same storms that dump snow in the Sierra Nevada, which makes them a particularly good proxy for snowpack.

According to Flint, scientists at the California Water Science Center have observed for several years that, as temperatures rise, more precipitation comes in the form of rain than snow. In the western United States, the rise in air temperatures has caused warmer winters that produce more rain than snow. The recent study compared snowpack and rainfall records, which confirmed that rising temperatures are causing precipitation dynamics to change. The results show that rising temperatures have resulted in a higher ratio of rain to snow in recent years.

"The problem there is that you can't store the water later in the season so that it melts and sustains the water supply throughout the summer," Flint said. Instead, she said, that water rushes into the ocean.

Flint agreed with Trouet's assessment that drought conditions are only going to worsen, but added, "Rising temperatures, regardless of the current drought situation, will continue to exacerbate [the natural water storage system] because more precipitation will fall as rain than as snow."

The researchers detailed their findings online Sept. 14 in the journal Nature Climate Change.

Follow Elizabeth Newbern @liznewbern. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus