Skull of Earliest Baboon Discovered

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

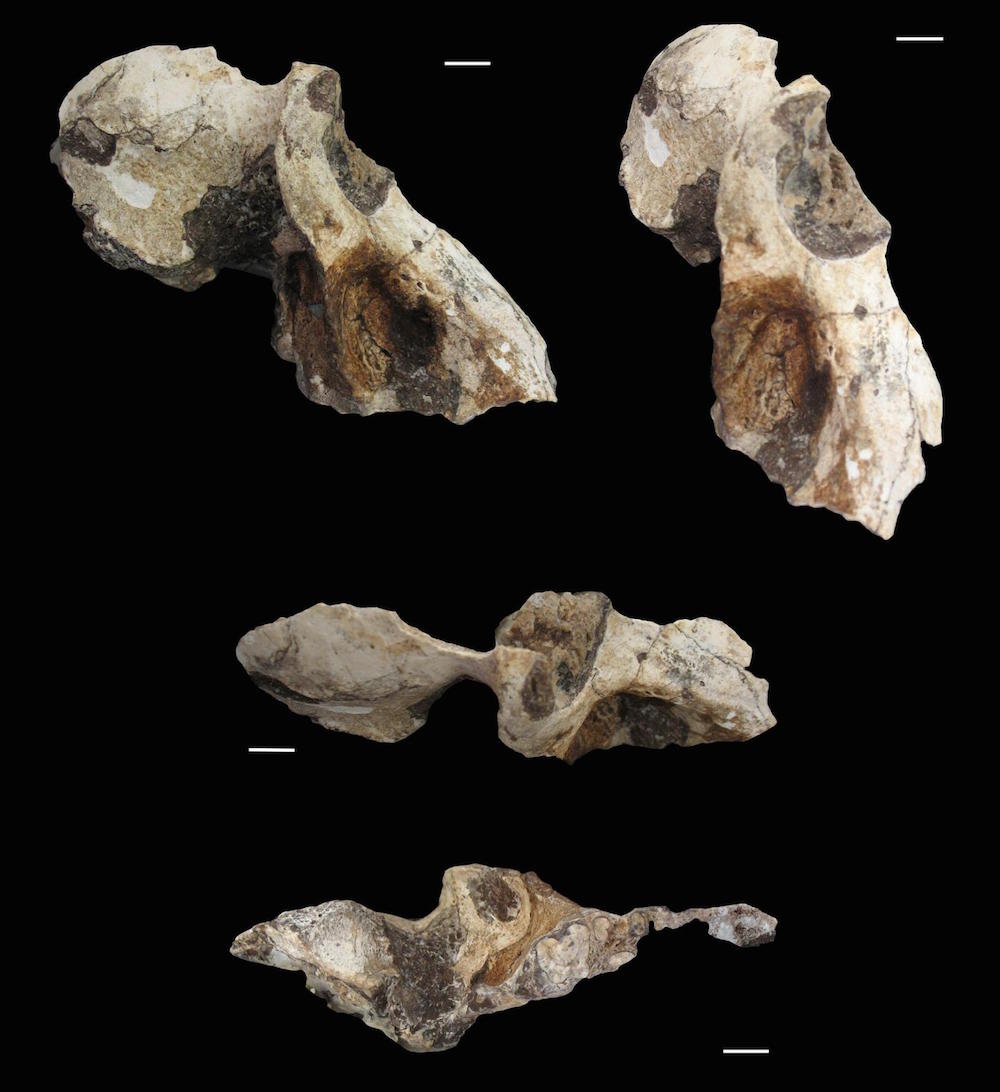

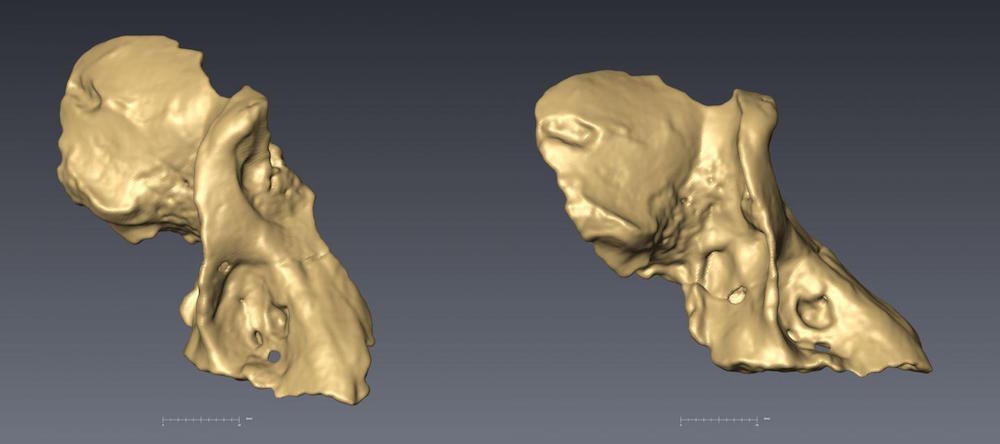

A 2-million-year-old skull unearthed in South Africa belongs to the earliest baboon ever found, a new study finds.

Researchers discovered the partial cranium at Malapa, a Cradle of Humankind World Heritage Site filled with caves and fossil deposits and located about 31 miles (50 kilometers) northwest of Johannesburg. In 2010, researchers at the Malapa fossil site uncovered the partial skeletons of the early hominin species, Australopithecus sediba.

"Baboons are known to have co-existed with hominins at several fossil localities in East Africa and South Africa, and they are sometimes even used as comparative models in human evolution," study lead author Christopher Gilbert, an assistant professor of anthropology at Hunter College, City University of New York, said in a statement.

Researchers found the baboon skull during excavations for A. sediba. The baboon — called UW 88-886 — is a member of Papio angusticeps, a species that is closely related to the modern baboon species Papio hamadryas, and may be related to some of its earliest known members, the researchers said. [In Photos: The Lives of Gelada Baboons]

Modern baboon species and subspecies live throughout sub-Saharan Africa and in the Arabian Peninsula. "[But] despite their evolutionary success, modern baboon origins in the fossil record are not well-understood or agreed upon," the authors wrote in the study, published online Wednesday (Aug. 19) in the journal PLOS ONE.

Molecular studies suggest that baboons diverged from their closest relatives by about 1.8 million to 2.2 million years ago, Gilbert said. But most fossil specimens from that time range are either too fragmentary or too primitive, making it difficult to confirm whether they are members of the living species (Papio hamadryas), he said.

"The specimen from Malapa and our current analyses help to confirm the suggestion of previous researchers that P. angusticeps may, in fact, be an early population of P. hamadryas," Gilbert said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers carefully studied the anatomy of UW 88-886 and other P. angusticeps fossils, and found that P. angusticeps has anatomy that is similar to modern baboons.

"If you placed a number of P. angusticeps specimens into a modern osteology collection, I don't think you'd be able pick them out as any different from those of modern baboons from East and South Africa," Gilbert said.

Moreover, UW 88-886 dates to about 2.026 million to 2.36 million years ago, which almost fits perfectly with the molecular clock analyses of when modern baboons first appeared, the researchers said.

Now that they know the time range in which P. angusticeps existed, researchers will have an easier time dating other fossils found near other members of the species, the researchers added.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus