Hurricanes of Terror: Why 2 Names Were Dropped from Storm List

Two hurricane names linked with terror and death were dropped from the Pacific storm list, the United Nations' World Meteorological Organization announced Friday (April 17).

The first, "Isis," was booted from the 2016 list of hurricane names because of its association with the brutal Islamic State militant group, the WMO said. Isis, the name of an ancient Egyptian goddess, was replaced with "Ivette."

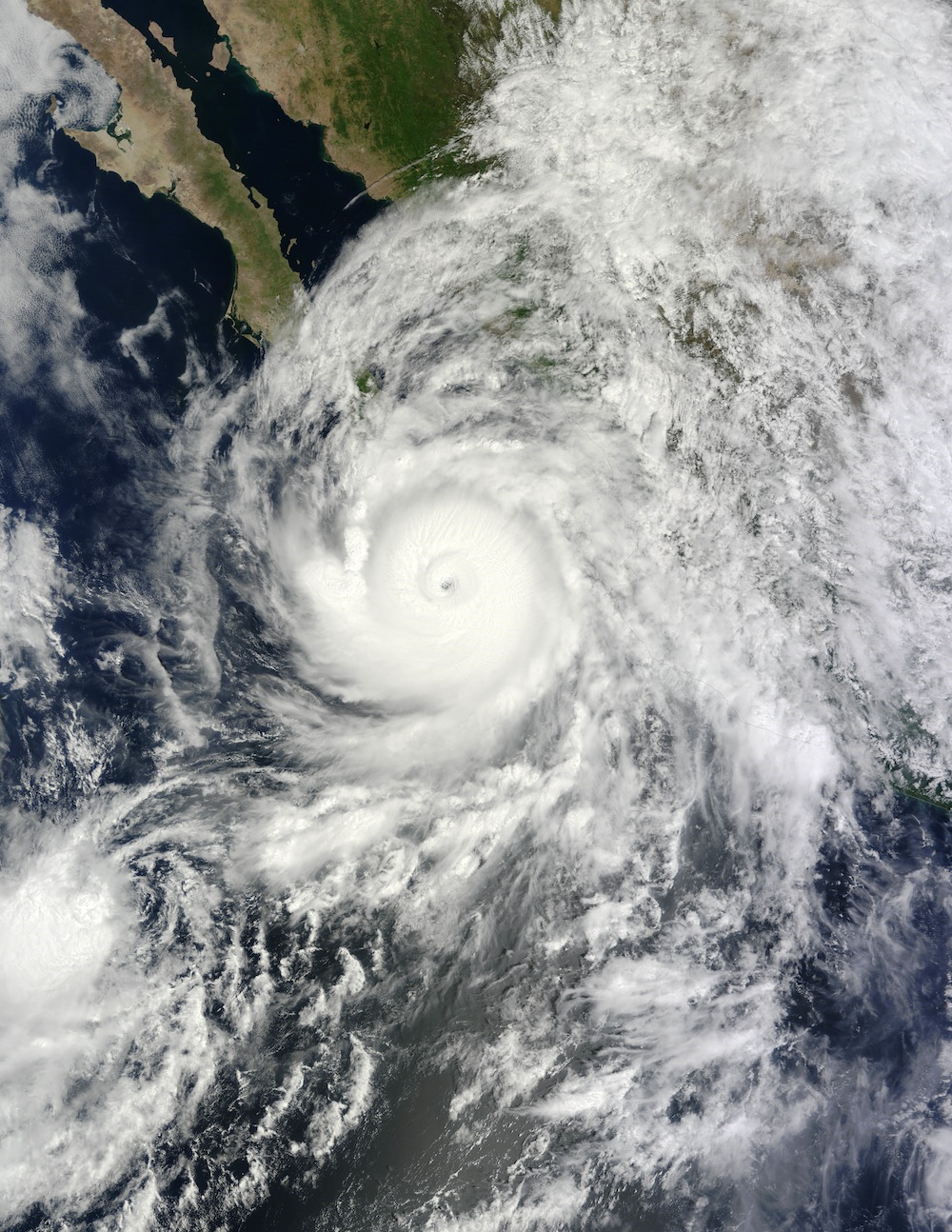

Worship of Isis was popular throughout the Mediterranean, from Egypt to Greece and the Roman Empire, until the Christian era. But ISIS also refers to the Islamic State, a militant group whose forces control large swathes of Iraq and Syria. ISIS is accused of ethnic cleansing and war crimes by the United Nations and Amnesty International. [Hurricanes from Above: See Images of Nature's Biggest Storms]

The second name, "Odile," lost its place on the 2020 list and was removed forever at Mexico's request. Hurricane Odile slammed the Baja Peninsula in September 2014 and was one of the most powerful hurricanes to hit Baja in the historical record. The storm killed 11 people and caused more than $1 billion in damage, according to the National Hurricane Center. The WMO swapped Odile for "Odalys."

A storm name is often struck from the lineup after a hurricane causes extraordinary damage or loss of life, according to the WMO. The name is then replaced with a new name starting with the same first letter. Famous storms erased from the list of names include Sandy (2012), Katrina (2005) and Mitch (1998).

There appears to be no precedent for purging a name because it is linked to a terrorist group. However, it makes sense to remove Isis, for the same reasons of sensitivity that underlie the damaging storm names, said Sharon Shavitt, a professor and behavioral psychologist at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign who has studied people's response to hurricane names.

"Imagine what would happen if Hurricane Isis would threaten to make landfall," Shavitt said. "Even though the choice was made years ago, there would be a lot of discussion and debate and head-scratching. It would have been odd to keep it in the rotation," she told Live Science.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Shavitt's research found the gender of hurricane names may influence people's perception of storm risk. Storms with female names kill more people than those with male names because of stereotypes that men are strong and aggressive and women are weaker and calmer, according to the study, published June 2, 2014, in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Such biases are much more subtle than the huge media storm that a Hurricane Isis could have triggered, Shavitt pointed out.

"When a name prompts discussion, any impact is going to be very different than names that go under the radar," she said.

The WMO hurricane naming committee meets once a year to mull over the names for future tropical cyclones and hurricanes. (Tropical cyclones include both hurricanes and typhoons.) The WMO committee considers names for storms that form in the Caribbean, Gulf of Mexico and North Atlantic Ocean; the North Pacific Ocean; and the South China Sea. Weather agencies in Japan, Australia and India label storms in the remaining oceans and seas.

There are six rotating lists of male and female storm names. For example, the 2014 list will appear again in 2020. The tally includes English, Spanish and French names, to reflect the languages spoken in countries where hurricanes rage. The National Hurricane Center started using an alphabetical list of female names in 1953. Men's names were added in 1979.

There was a deadly Hurricane Isis in 1998, and the name was used again in 2004 for a weaker hurricane. Isis was also on the 2010 name list but wasn't used that year.

Follow Becky Oskin @beckyoskin. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.