6 strangest hearts in the animal kingdom

Hearts have become iconic symbols of Valentine's Day, but when it comes to hearts in the real world, one size doesn't fit all — particularly in the animal kingdom. At rest, the human heart beats between 60 and 80 times a minute, but in that same time, a hibernating groundhog's heart beats just five times and a hummingbird's heart reaches 1,260 beats per minute during powered flight. The human heart weighs about 0.6 pounds (0.3 kilograms), but a giraffe's weighs about 25 pounds (11 kg), as the organ needs to be powerful enough to pump blood up the animal's long neck. Here are some other creatures with strange hearts.

1. Frogs

Mammals and birds have four-chambered hearts, but frogs have just three, with two atria and one ventricle, said Daniel Mulcahy, a research collaborator of vertebrate zoology who specializes in amphibians and reptiles at the Smithsonian Institution, Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C.

In general, the heart takes deoxygenated blood from the body, sends it to the lungs to get oxygen, and pumps it through the body to oxygenate the organs, he said. In humans, the four-chambered heart keeps oxygenated blood and deoxygenated blood in separate chambers. But in frogs, grooves called trabeculae keep the oxygenated blood separate from the deoxygenated blood in its one ventricle.

Frogs can get oxygen not only from their lungs, but also from their skin, Mulcahy said. The frog's heart takes advantage of this evolutionary quirk. As deoxygenated blood comes into the right atrium, it goes into the ventricle and out to the lungs and skin to get oxygen.

The oxygenated blood comes back to the heart through the left atrium, then into the ventricle and out to the major organs, Mulcahy said.

Even weirder are the hearts of freeze-tolerant frogs, including the wood frog (Lithobates/Rana sylvaticus), whose heart completely stops when the frog freezes during winter hibernation, and then starts beating again within one hour of thawing, according to a 1989 study in the American Journal of Physiology.

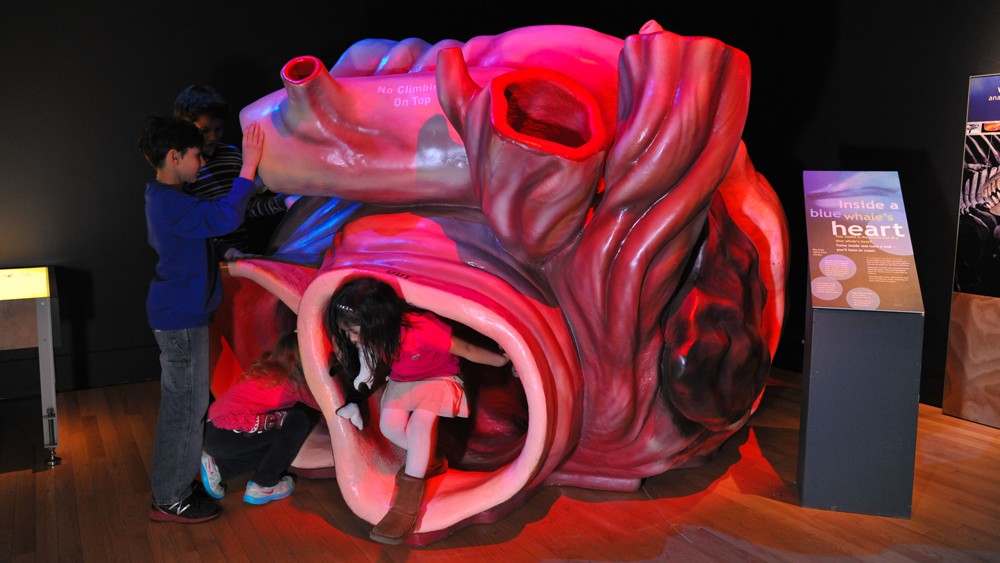

2. Whales

The blue whale's heart is the largest of all the animals living today. "It is the size of a small car and has been weighed at about 950 pounds [430 kg]," said James Mead, a curator emeritus of marine mammals in the department of vertebrate zoology at the National Museum of Natural History at the Smithsonian Institution. Like other mammals, the whale's heart has four chambers.

The organ is responsible for supplying blood to an animal the length of two school buses, said Nikki Vollmer, an assistant scientist for the Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies working with the NOAA Fisheries' Southeast. "The walls of the aorta, the main artery, can be as thick as an iPhone 6 Plus is long," or over 6 inches (15 centimeters), Vollmer told Live Science. "That is a thick-walled blood vessel!"

When blue whales dive deep into the ocean, their heart rate slows to four beats per minute, which helps them extend their dive time and may even mitigate decompression sickness, known as the bends. That's because this lower heartbeat lowers the passage of blood into the pressurized lungs, and the in-hand reduction of nitrogen uptake may alleviate the bends, a 2021 study in the journal Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology reported.

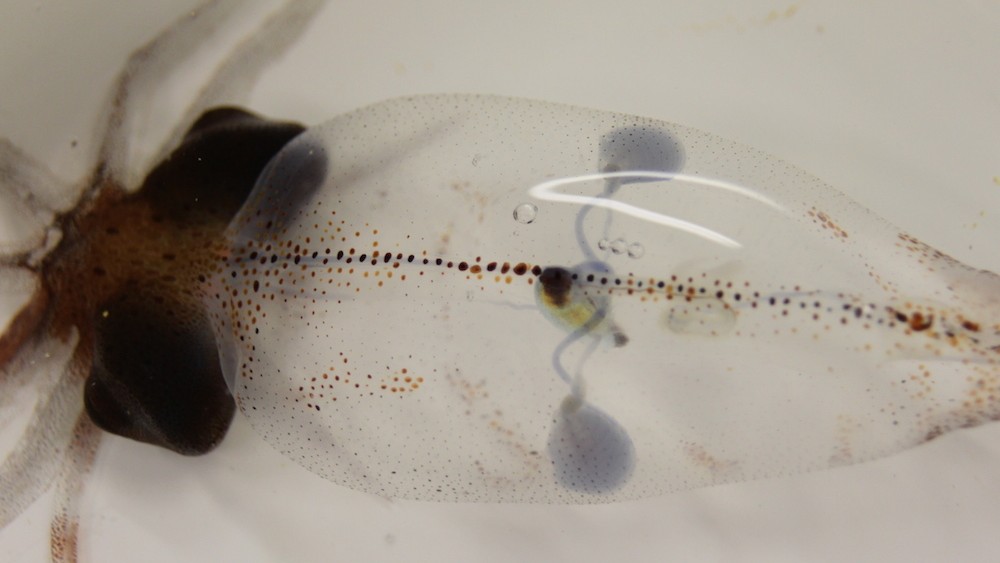

3. Cephalopods

There's nothing half-hearted about cephalopods. These tentacular and armed marine creatures, including the octopus, squid and cuttlefish, have three hearts apiece.

Two brachial hearts on either side of the cephalopod's body oxygenate blood by pumping it through the blood vessels of the gills, and the systemic heart in the center of the body pumps oxygenated blood from the gills through the rest of the organism, said Michael Vecchione, an invertebrate zoologist at the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History.

Cephalopods are also literally blue-blooded because they have copper in their blood. Human blood is red because of the iron in hemoglobin. "Just like rust is red, the iron in our hemoglobin is red when it's oxygenated," Vecchione said. But in cephalopods, oxygenated blood turns blue.

4. Cockroaches

Like other insects, the cockroach has an open circulatory system, meaning its blood doesn't fill blood vessels. Instead, the blood flows through a single structure with 12 to 13 chambers, said Don Moore III, a senior scientist at the Smithsonian's National Zoo in Washington, D.C.

The dorsal sinus, located on the top of the cockroach, helps to send oxygenated blood to each chamber of the heart. But the heart isn't there to move around oxygenated blood, Moore said.

"Roaches and other insects breathe through spiracles [surface openings] in the bodies instead of lungs, so the blood doesn't need to carry oxygen from one place to another," Moore said.

Instead, the blood, called hemolymph, carries nutrients and is white or yellow, he said. The heart doesn't beat by itself, either. Muscles in the cavity expand and contract to help the heart send hemolymph to the rest of the body.

The heart is often smaller in wingless cockroaches than in flying ones, Moore said. The cockroach's heart beats at about the same rate as a human heart, he added.

5. Earthworms

The earthworm can't take heart, because it doesn't have one. Instead, the worm has five pseudohearts that wrap around its esophagus. These pseudohearts don't pump blood, but rather they squeeze vessels to help circulate blood throughout the worm's body, Moore said.

It also doesn't have lungs, but absorbs oxygen through its moist skin."Air trapped in the soil, or aboveground after a rain when worms can stay moist, dissolves in the skin mucus, and the oxygen is drawn into the cells and blood system where it is pumped around the body," Moore said.

Earthworms have red blood that contains hemoglobin, the protein that carries oxygen, but unlike people worms have an open circulatory system. "So the hemoglobin just kind of floats among the rest of the fluids," Moore said.

6. Fish

If a zebrafish has a broken heart, it can simply regrow one. A study published in 2002 in the journal Science found that zebrafish can fully regenerate heart muscle just two months after 20% of their heart muscle is damaged.

Humans can regenerate their liver, amphibians and some lizards can regenerate their tails, and frogs given a special drug cocktail even regrew legs in a 2022 study in the journal Science Advances, but the zebrafish's regenerative abilities make it a prime model to study heart growth, Moore said.

However, fish have unique hearts. In addition to the one atrium and one ventricle, fish also have two structures that aren't seen in humans. The "sinus venosus" is a sac that sits ahead of the atrium and the "bulbus arteriosus" is a tube located just behind the ventricle.

As in other animals, the heart drives blood throughout the body. Deoxygenated blood enters the sinus venosus and flows into the atrium, Moore said. The atrium then pumps the blood into the ventricle.

The ventricle has thicker, more muscular walls, and pumps the blood into the bulbus arteriosus. The bulbus arteriosus regulates the pressure of the blood as it flows through the capillaries surrounding the fish's gills. It is in the gills where there is oxygen exchange across cell membranes and into the blood, Moore said.

But why does the fish need the bulbus arteriosus to regulate blood pressure?

"Because the gills are delicate and thin-walled — any fisherman knows this — and can be damaged if the blood pressure is too high," Moore said. "The bulbus arteriosus itself is apparently a chamber with very elastic components compared to the muscular nature of the ventricle."

Editor's note: Originally published on Feb. 13, 2015 and updated on Feb. 14, 2022.

Originally published on Live Science.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.