Remote European Ice Now Racing into the Sea

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

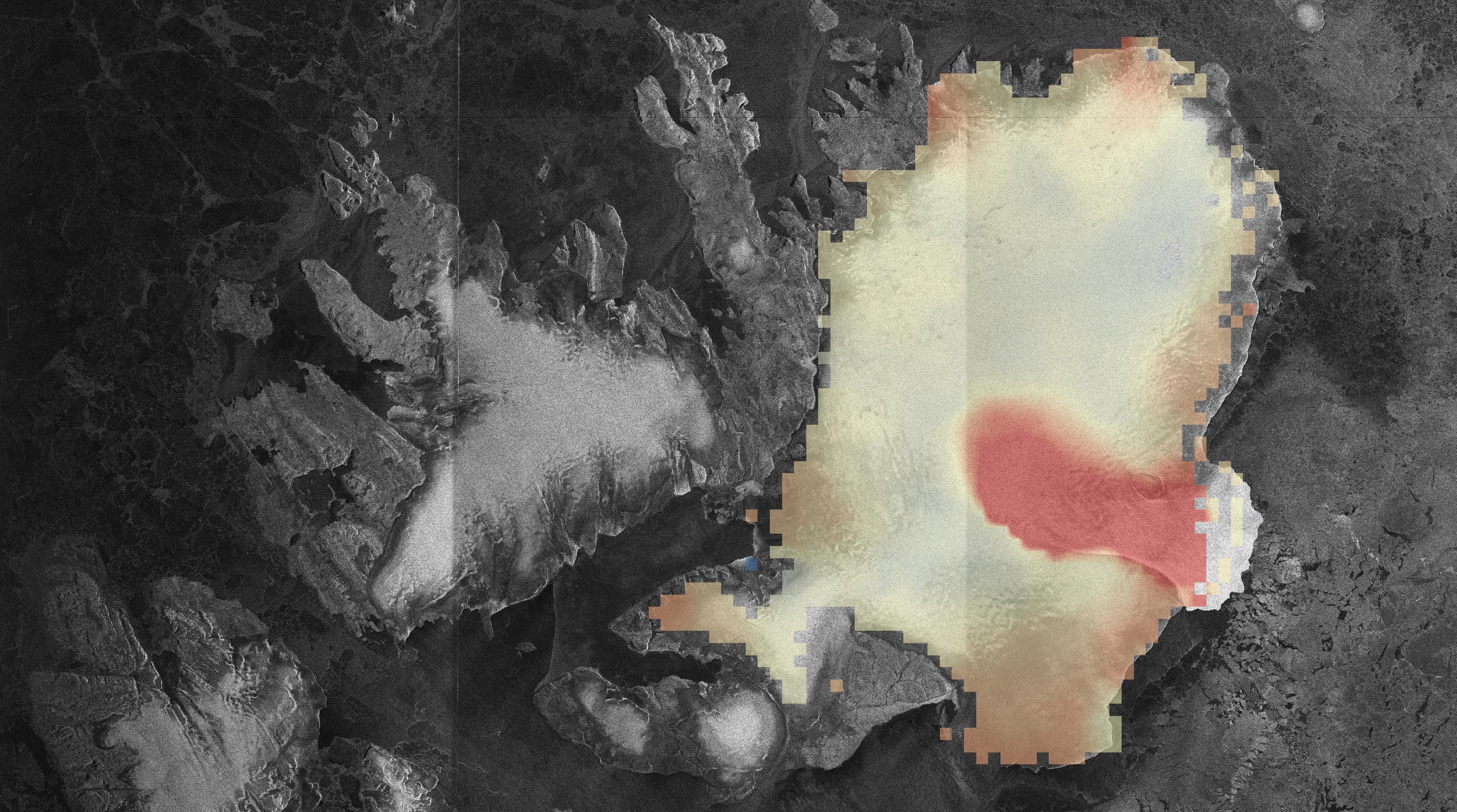

A remote ice cap in northern Europe, above the Arctic Circle, is shedding so much weight that it now races toward the sea 25 times faster than it did in 1995, a new study finds.

The Austfonna ice cap, which hugs an island offshore northeastern Norway in the Svalbard archipelago, holds about 600 cubic miles of ice (2,500 cubic kilometers) — a volume bigger than most glaciers but smaller than the Greenland or Antarctic ice sheets. Most of this ice cap sits on land, but on the island's eastern side, the ice floats outward into the Barents Sea.

Now, observations from eight satellites reveal that the ice cap is shrinking significantly faster than it was 20 years ago, especially where the ice sticks a tongue into the sea, according to a study published online Dec. 23, 2014, in the journal Geophysical Research Letters (GRL).

"What we see here is unusual because it has developed over such a long period of time, and appears to have started when ice began to thin and accelerate at the coast," Andrew Shepherd, a study co-author and a professor at the University of Leeds in the United Kingdom, said in a statement.

The most significant changes were seen in the past five years in a glacier called Basin-3 within the eastern ice cap, the researchers said. Basin-3 is surging for the first time in 140 years, shooting forward at an incredible speed. But starting in 2009, the ice also started rapidly thinning. (In general, a surge in a glacier is not directly related to its ice loss or gain.) [10 Things You Need to Know About Arctic Sea Ice]

Resembling a cinched belt, this zone of shrinking ice now forms a tight band stretching from the coast to within 6 miles (10 km) of the center of the ice cap. Basin-3 could be dumping more ice into the ocean than all of Svalbard's other glaciers combined, according to a paper under review for publication in the journal The Cryosphere. For instance, between 2012 and 2014, the glacier shrank in height by 165 feet (50 meters), the GRL study reported.

The same shrinking glacier also gallops more rapidly toward the sea than it used to, the study reported. By 2014, the ice was flowing at 2.4 miles per year (3.8 km per year) — a 25-fold increase over the 82 feet per year (25 m per year) measured in 1995. Although the Austfonna ice cap has launched rapid ice surges in the past, according to historical records, none have lasted as long as the current uptick, according to the study.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers said there are several possible explanations for the dramatic transformation of the Austfonna ice cap, including natural causes. A different Austfonna glacier surged 12 miles (20 km) between 1935 and 1936. Climate change is a likely culprit, but air temperatures have remained relatively stable in this corner of the Arctic because of local variations, the study reported. (Overall, surface temperatures in the Arctic have doubled compared to the global average.)

Instead, the scientists plan to investigate the effects of warming ocean currents on the ice. Many models suggest that ocean warming is melting glaciers in Greenland, Antarctica and elsewhere from below, contributing to sea level rise. However, directly observing this process is difficult for many reasons, such as the danger involved in trying to peer beneath potentially lethal ice.

"Whether or not the warmer ocean water and ice cap behavior are directly linked remains an unanswered question," Shepherd said in the statement. "Feeding the results into existing ice flow models may help us to shed light on the cause, and also improve predictions of global ice loss and sea level rise in the future."

Follow Becky Oskin @beckyoskin. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus