No Evidence of Megatsunamis Slamming California Coast

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Several deadly tsunamis hit California in the past four centuries, but there's no evidence of a devastating megatsunami, according to a new report from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS).

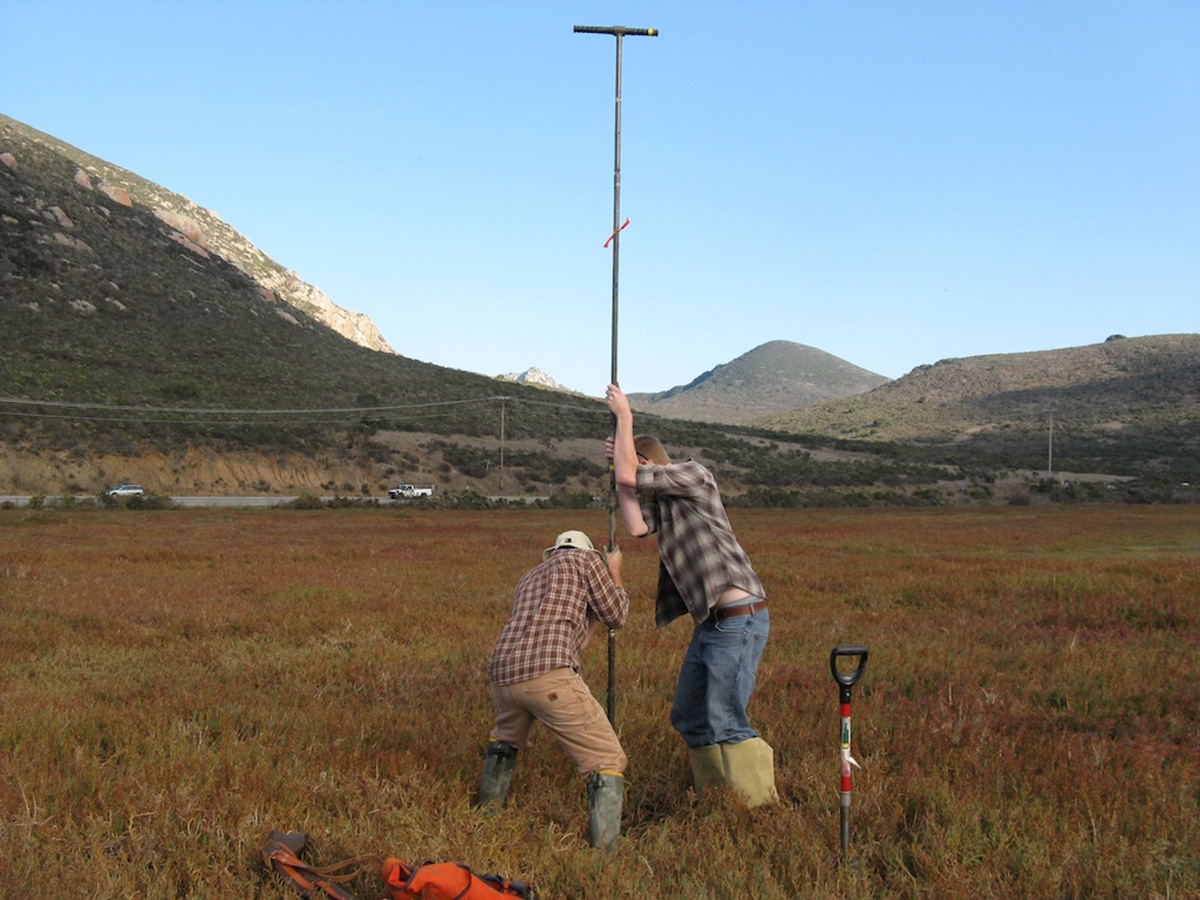

Geologists from the USGS, the California Geological Survey and Humboldt State University searched for evidence of ancient tsunamis at more than 20 sites along 683 miles (1,100 kilometers) of shoreline, from Crescent City in the north to the Tijuana River estuary in the south.

Only two spots preserved strong evidence of past tsunamis — Crescent City and Half Moon Bay, both in Northern California. The sand layers at these spots matched up with waves from historic earthquakes, one offshore of Washington's Cascadia subduction zone in 1700, and two others in 1946 and 1964 in Alaska.

In Crescent City, the earthquake-triggered tsunami in 1700 traveled up to 1.2 miles (2 km) inland. The 1946 and 1964 Alaska earthquakes and related tsunamis both damaged docks and buildings at Crescent City and killed California residents. But none of the evidence points to waves as damaging as those that hit Japan in 2011 or Sumatra in 2004. [Waves of Destruction: History's Biggest Tsunamis]

"We haven't found evidence for a megatsunami in the recent geologic record," said study co-author Bruce Richmond, a research geologist with the USGS Pacific Coastal and Marine Science Center in Santa Cruz, California.

But Richmond and his co-authors warned that California shouldn't see the report as a signal to ignore tsunami hazards.

"We may not get huge tsunamis, but we can still be impacted by tsunamis," Richmond told Live Science's Our Amazing Planet.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

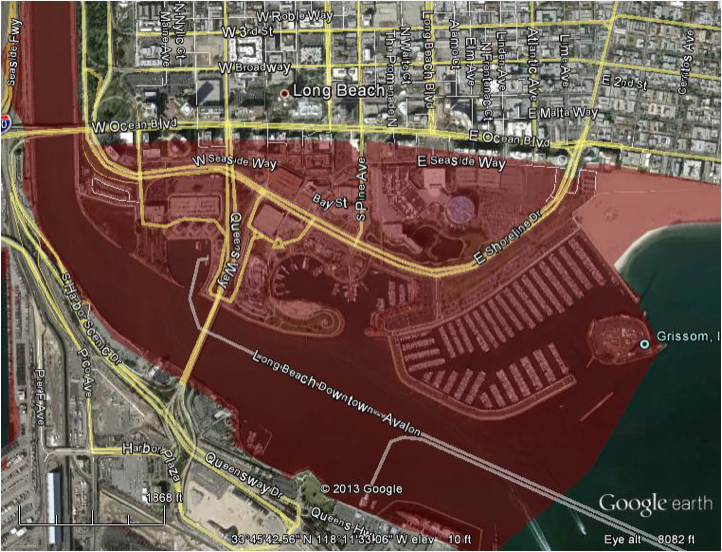

The massive coastal survey was part of an effort to better estimate California's risk from tsunamis. Computer models created for the same project show that harbors and marinas all along the coast are at risk of major flooding during a Pacific Ocean tsunami. (These computer models are akin to those that predict where a tsunami will strike soon after an earthquake occurs.)

A direct hit by waves from Alaska could cause billions in damage. Japanese earthquakes are another likely source of tsunamis. (The 2011 Tohoku, Japan, tsunami killed one person and caused $100 million in damage in California.) Emergency planners also worry about an earthquake along the Cascadia subduction zone — where one of Earth's plates dives beneath another — which stretches from Vancouver, Canada, to Northern California.

Earthquakes at subduction zones, such as those along Alaska and Japan, shift the seafloor and generate a paddlelike effect that triggers a tsunami. Tsunami waves can soar to staggering proportions as they near the shore. Underwater landslides also can launch a tsunami.

Most of California does not have an offshore subduction zone that would generate a tsunami, but its big earthquakes could trigger an underwater landslide. The research team is now studying sand layers at Carpinteria, near Santa Barbara, for evidence of tsunamis caused by earthquake-generated landslides.

Tsunami deposits are usually thin, continuous sand layers with unique characteristics that help to differentiate them from storm deposits. They're most commonly found in marshes, ponds and lagoons, where the sand layer sharply contrasts with dark, organic-rich material that typically builds up in marshes and lagoons.

But researchers found few of these tsunami sand layers in California's coastal marshes. Instead, evidence of past tsunamis was most common in shallow ponds, where the sand carried by big waves was deposited and preserved in standing water.

"I think we have a poor chance of preserving deposits from tsunamis that came all the way across the Pacific," said study co-author Eileen Hemphill-Haley, a geologist at Humboldt State University in Arcata, California. "They would have wave heights that are destructive to coastal properties, but we're not talking a wall of water like they had in Tohoku."

The report was published online May 20 by the USGS.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @OAPlanet, Facebook and Google+. Original article at Live Science's Our Amazing Planet.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus