Lab-Grown Vaginas Implanted in 4 Girls

Researchers have grown vaginas in a lab, and the organs are working normally in four teenage patients who were among the first people to receive such an implant, scientists reported today.

All of the patients in the study underwent surgery five to eight years ago because they were born with a rare genetic condition in which the vagina and uterus are underdeveloped or absent.

Scientists grew each vagina from the patient's own cells, and then implanted it in her body. So far in the follow-up, the treatment has been successful, and the patients who are now sexually active have reported normal function, according to the study, published today (April 10) in the journal Lancet. [7 Facts Women (And Men) Should Know About the Vagina]

Although this is a small pilot study, the results show that vaginal organs can be constructed in the lab and used successfully in people, said study researcher Dr. Anthony Atala, director of Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center's Institute for Regenerative Medicine.

Although more research needs to be done, growing vaginal tissue from a person's own cells could potentially be a new treatment option for patients with vaginal cancer or injuries who require reconstructive surgeries, the researchers said.

"A lot of what we are doing right now is really applicable to patients who have deformity or abnormal organs for many other conditions — of course, the most prominent being cancer — [and] also patients who may have an injury in the area," Atala said.

The girls in the study had a congenital deformation called Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser (MRKH) syndrome, which affects between one in 1,500 and one in 4,000 female infants, the researchers said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To build the personalized vaginas, the researchers took a small piece of vulvar tissue, less than half the size of a postage stamp, from each patient, and then allowed the cells to multiply in lab dishes.

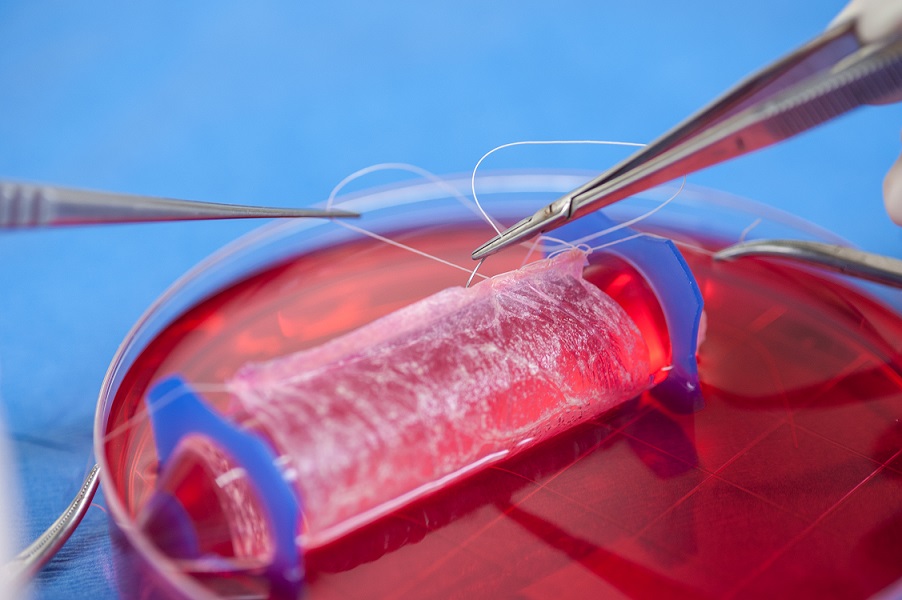

The vagina is made up of two major layers with two cell types: muscle cells and vaginal epithelial cells. To build these layers, the researchers placed one cell type on one face of a scaffold, made of a fabriclike material, and placed the other cell type on the other face of the scaffold.

"We were able to shape the scaffold specifically for each patient, and place this device with the cells in a bioreactor — which is an ovenlike device and has the same conditions as the human body — for about a week, until it was slightly more mature," Atala said.

Once the organs were ready, doctors surgically created a cavity in the patients' bodies, and stitched one side of the vaginal organ to the opening of the cavity and the other side to the uterus.

"The whole process takes about five to six weeks, from the time we take the tissue from the patient to the time we actually plant the engineered construct back into the patient," Atala said.

The girls were between 13 and 18 years old at the time of their surgeries. Researchers followed up with the patients every year for five to eight years, and examined the organs using X-rays and biopsies to check their structure. Patients also reported on the organs' functionality, including the sexual function.

Data from these yearly follow-up visits show that up to eight years after the surgeries, the organs had normal function, including normal sexual functions, such as desire and pain-free intercourse, according to the study.

Current treatments for MRKH syndrome include dilation of existing tissue or, for more severe cases, reconstructive surgery using a piece of intestine or a piece of skin to create a new vaginal organ.

However, the risk of complications is high with these techniques because the tissue substitute is not vaginal tissue, Atala said. "They are not ideal because they don't perform the same functionality," he said.

Email Bahar Gholipour. Follow us @LiveScience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.