Scientists have digitally removed the 'death masks' from four Colombian mummies, revealing their faces for the first time

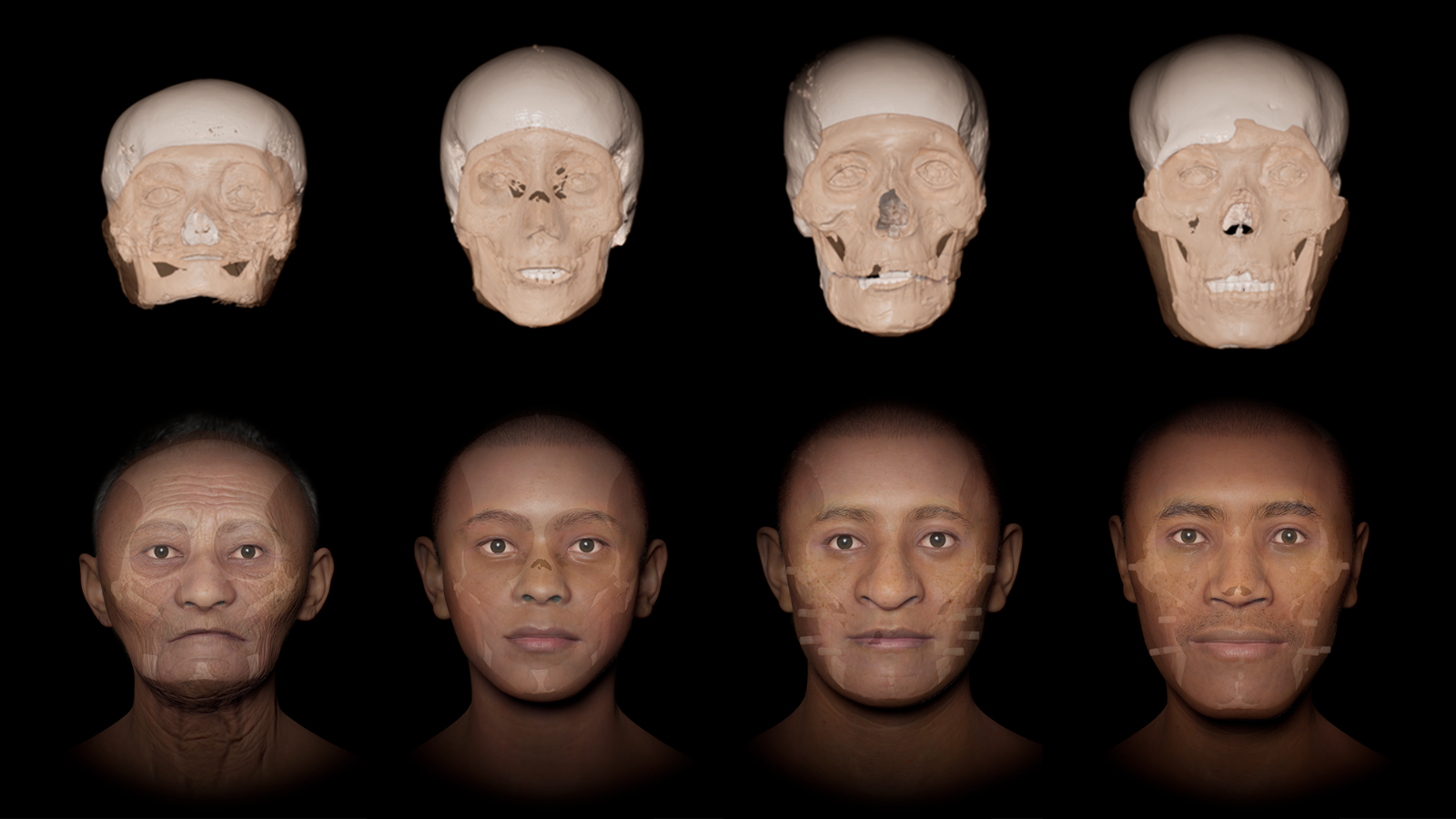

The reconstructions are based on the skulls of four mummified individuals who had masks tightly fitted on their faces.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Centuries-old mummies from the Andes of Colombia have been digitally unmasked and virtually reconstructed, revealing how they may have looked during their lifetimes.

These individuals, who lived sometime between the 13th and 18th centuries, were buried with death masks covering their faces and jaws. They're the only Colombian examples of a cultural practice otherwise common for communities in other parts of pre-Columbian South America. However, as their graves were looted, little was known about these four individuals and their archaeological context.

Now, researchers have digitally "unmasked" their skulls to reconstruct their faces, which they presented for the first time Aug. 14 during the 11th World Congress on Mummy Studies in Peru.

These reconstructions highlight "the fascinating cultural practices" of the Indigenous peoples who lived in South America, Jessica Liu, the project manager for Face Lab at Liverpool John Moores University in the U.K, said in a statement about the project.

The mummies are of a 6- to 7-year-old child, a female in her 60s and two young adult males, all with stylized masks made of resin, clay, wax and maize attached to their faces. All the masks are damaged, with missing noses and chunks along the base, but some ornamental beads outlining the eyes remain. The individuals were from pre-Hispanic populations in the Eastern Cordillera, a region in the Colombian Andes, with radiocarbon dating indicating they lived between 1216 and 1797.

CT scans were performed on the masked skulls. CT scans use X-rays to generate virtual 3D images by taking lots of images of 2D slices of a sample and putting them together. Because of this, the team could "effectively unmask the skull digitally" by removing the layers containing the mask, Liu told Live Science.

Next, the researchers used specialized software and a haptic touch stylus pen to superimpose muscles, soft tissue and fat onto the digitally unmasked skulls. Liu said this is like virtual sculpting, where you use the scaffolding of the skull to get the tissue to perfectly fit the individual.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The team used average facial tissue depth data from modern-day adult male Colombians to add the soft tissue to the two young adult male skulls. The team did not use such data to add soft tissue onto the other two skulls as no contemporary tissue data currently exists for Colombian children and females. However, they still reconstructed these faces, adding the muscles and tweaking them to fit each particular skull, and bulking out the child's face with some fat. The nose size and shape was determined by measuring the bony tissues of the skull and then selecting the best-fitting nose out of an array of options.

The team gave the individuals the skin, eye and hair color typical of individuals from the region, and gave them a neutral facial expression. Next came the hard part, Liu said, because they then had to add the facial "texture": wrinkles, eyelashes, freckles and pores. This is a long process of making constant changes until they find the best fit.

"Texture is always the biggest challenge, just because we simply don't know how they would present themselves, whether or not they have any facial scarring or tattoos, or if that actually is the skin tone," Liu said. "What we present in terms of texture is an average representation, based on what we know of these individuals."

This is an important point, Liu said, because they are creating faces based on group averages, "but nobody is ever an average." This means that these freshly unmasked faces are not accurate portraits of these individuals; they show "what they could have looked like rather than 'this is what they looked like'," she said.

Mummy quiz: Can you unwrap these ancient Egyptian mysteries?

Sophie is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She covers a wide range of topics, having previously reported on research spanning from bonobo communication to the first water in the universe. Her work has also appeared in outlets including New Scientist, The Observer and BBC Wildlife, and she was shortlisted for the Association of British Science Writers' 2025 "Newcomer of the Year" award for her freelance work at New Scientist. Before becoming a science journalist, she completed a doctorate in evolutionary anthropology from the University of Oxford, where she spent four years looking at why some chimps are better at using tools than others.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus