What is Stigmata?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

People who have stigmata exhibit wounds that duplicate or represent those that Jesus is said to have endured during his crucifixion. The wounds typically appear on the stigmatic's hands and feet (as from crucifixion spikes) and also sometimes on the side (as from a spear) and hairline (as from a crown of thorns).

Along with possession and exorcism, stigmata often appears in horror films, and it's not difficult to see why: bloody wounds that mysteriously and spontaneously open up are terrifying. However, stigmatics, who are typically devout Roman Catholics, do not see their affliction as a terrifying menace but instead as a miraculous blessing — a sign that they have been specially chosen by God to suffer the same wounds his son did.

Curiously, there are no known cases of stigmata for the first 1,200 years after Jesus died. The first person said to suffer from stigmata was St. Francis of Assisi (1182-1226), and there have been about three dozen others throughout history, most of them women.

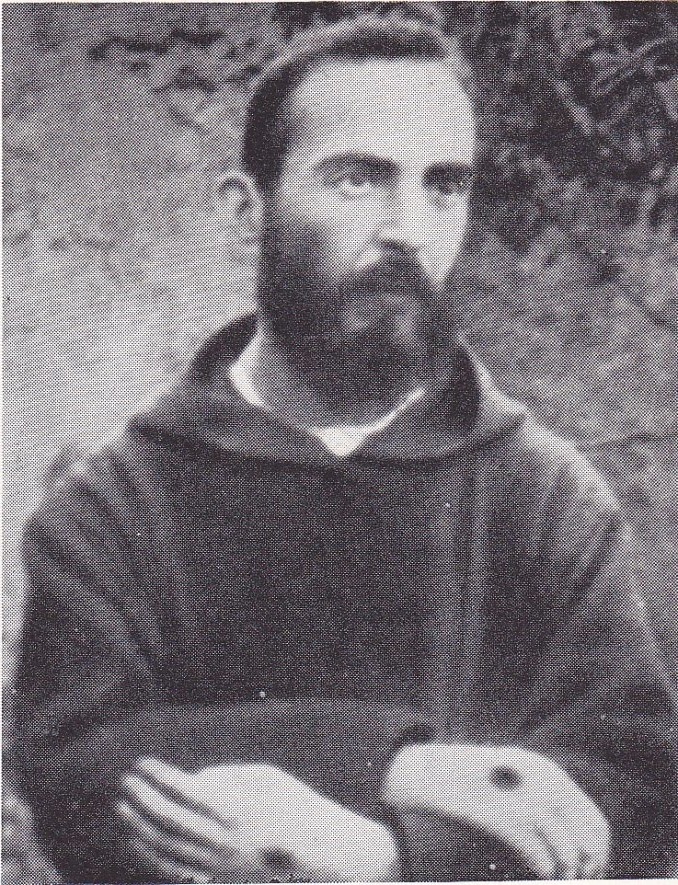

Padre Pio

The most famous stigmatic in history was Francesco Forgione (1887-1968), better known as Padre Pio, or Pio of Pietrelcina. The most beloved Italian saint of the last century, Padre Pio first began noticing red wounds appearing on his hands in 1910, and the phenomenon progressed until he experienced full stigmata in 1918 as he prayed in front of a crucifix in his monastery's chapel.

Padre Pio was said to have been able to fly, and also to bilocate (to be in two places at once); his stigmata was allegedly accompanied by a miraculous perfume; the Rev. Charles Mortimer Carty, in his 1963 biography of the saint, noted that it smelled of "violets, lilies, roses, incense, or even fresh tobacco," and "whenever anyone notices the perfume it is a sign that God bestows some grace through the intercession of Padre Pio."

Journalist Sergio Lizzatto, in his book "Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age" explains the social context in which Padre Pio's stigmata emerged: "In the first years of the twentieth century, when Padre Pio was a seminarian, the Eucharist — the body and blood of Christ — was at the height of its importance in Catholic practice. Communion was celebrated frequently and became a mass phenomenon. At the same time, asceticism was interpreted in ever more physical terms. Body language — ecstasy, levitation, the stigmata — was held to be the only real mystical language."

Pio's stigmata appeared, Lizzatto argues, because that's exactly what the church and its followers expected to appear in its most devout servants: Jesus' real, physical torment visited upon the holiest of men.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Though Padre Pio was widely beloved, many weren't convinced that the friar's wounds were supernatural. Among the skeptics were two popes and the founder of Milan's Catholic University of the Sacred Heart, Agostino Gemelli, who examined Padre Pio and concluded that the stigmatic was a "self-mutilating psychopath."

Still, Padre Pio garnered a widespread following and was canonized by Pope John Paul II in 2002. Though Pio, who died in 1968, never confessed to faking his stigmata, questions about his honesty surfaced when it was revealed that he had copied his writings about his experiences from an earlier stigmatic named Gemma Galgani. He claimed ignorance of Galgani's work, and could not explain how his allegedly personal experiences had been published verbatim decades earlier by someone else. Perhaps, he suggested, it was a miracle.

Is stigmata real?

So is stigmata real, or a hoax, or something in between? The claimed miracle of stigmata — like inedia, where people who claim not to eat food — is very difficult to scientifically verify. Veteran researcher James Randi, in his "Encyclopedia of Claims, Frauds, and Hoaxes of the Occult and Supernatural," notes that "Since twenty-four-hour-a-day surveillance would be necessary to establish the validity of these phenomena as miracles, no case of stigmata exists that can be said to be free of suspicion," and though the possibility of genuine stigmata can never be ruled out, "It is interesting to note that in all such cases, the wounds in the hands appear at the palms, which agrees with religious paintings but not with the actualities of crucifixion; the wounds should appear at the wrists."

If stigmata is real, there is no medical or scientific explanation for it. Wounds do not suddenly and spontaneously appear on people's bodies for no reason; some specific instrument (such as a knife, tooth, or bullet) can always be identified as causing the trauma. Without a medical examination, it is impossible to distinguish a minor (but bloody) surface wound (which could be easily faked or self-inflicted) from a genuine and serious puncture wound identical to that caused by a Roman-era crucifixion spike. X-rays, which could definitively determine whether a wound is superficial or truly pierces a limb, have never been done on stigmatics.

There are no documentary photographs, films or videos of wounds appearing and beginning to bleed; instead the evidence for the existence of stigmata comes from eyewitnesses who see wounds that are already bleeding, and whose origin explanation must be taken on faith. It is of course considered highly disrespectful to challenge the honesty and integrity of a person who claims (and appears) to be suffering from Christ's wounds. Stigmatics appear to be sincere, and almost certainly often are in at least some pain even if a wound is superficial. It takes a brave skeptic to accuse a beloved friar of fraud or faking the wounds — even if that's what the evidence clearly suggests.

The fact that many of the faithful take comfort and inspiration from the teachings of stigmatics also serves as a deterrent from raising too many questions. Even those with legitimate suspicions may prefer to remain silent if it helps spread the gospel and serves a larger purpose. Until a person suffering from stigmata allows himself or herself to be subjected to close medical scientific investigation, the phenomenon will remain a myth.

Benjamin Radford, M.Ed., is deputy editor of Skeptical Inquirer science magazine and author of six books including Scientific Paranormal Investigation: How to Solve Unexplained Mysteries. His website is www.BenjaminRadford.com.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus